Writing End of Life Stories

categories: Cocktail Hour

2 comments

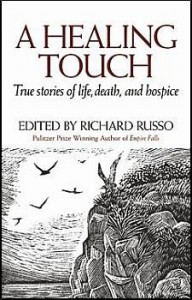

A couple of years ago, I was part of a project called A Healing Touch, which was a beautiful short volume edited by Richard Russo, a collection of true stories about hospice and death to benefit the Hospice Volunteers of the Waterville Area. Six Maine writers took part, donating their share of royalties: Monica Wood, Wesley McNair, Gerry Boyle, Susan Sterling, Mr. Russo and myself, a matter of interviewing people who’d been helped by hospice and telling their stories. The project has been successful in many ways (including a pretty generous royalty check or two or three to the HVWA from the book’s publisher, ), but one particular way it was successful was making it clear to readers and ultimately to me that hospice is not only for the dying.

A couple of years ago, I was part of a project called A Healing Touch, which was a beautiful short volume edited by Richard Russo, a collection of true stories about hospice and death to benefit the Hospice Volunteers of the Waterville Area. Six Maine writers took part, donating their share of royalties: Monica Wood, Wesley McNair, Gerry Boyle, Susan Sterling, Mr. Russo and myself, a matter of interviewing people who’d been helped by hospice and telling their stories. The project has been successful in many ways (including a pretty generous royalty check or two or three to the HVWA from the book’s publisher, ), but one particular way it was successful was making it clear to readers and ultimately to me that hospice is not only for the dying.

Very often, my life stories classes have encompassed death stories, and around these stories it is impossible to be cynical about teaching the art of memoir. One student I can’t forget was a scientist in one of the many community writing workshops I’ve led over the years. (I’ll disguise things lightly here so as not to breach her family’s privacy). Dr. Sue had been diagnosed with the same rare form of cancer her mother and several sisters had already died of. She’d been given about two years to live when I met her, and though she wasn’t a writer by profession or habit, she very much wanted to write her life in the time she had left. Why? Well, she had two young children, and wanted them when they grew up to know her beyond the vague memories they were likely to be left with. First night of class as we talked about everyone’s goals for the ten weeks she said something like, “I don’t want my son and daughter to grow up and try to find me in my professional writing or in my resume. That stuff is all good, and I’m proud of it, but it’s all arcane chemistry, and really says nothing about me at all, except that I’m a good scientist.” She had started writing energetically on her own, but had found after a few pages into several false starts that it was really hard and then impossible to know what to say, or who in fact she actually was. What was important? What was mere narcissism, self-serving nonsense? How could she bridge the gap between her seemingly numbers-oriented science self and her truly warm and human heart?

Using exercises such as mapping her childhood neighborhood, creating timelines, making constellations of family and friends, we got Dr. Sue to start telling stories, and then, through more exercises, got her filling the stories out with deeper and deeper detail and understanding. Next we stood back from the evidence she’d created and got her to think about what was evident, what it all meant, who, in fact, she really was, and so how she wanted to be remembered. After a while we added a few research tools, research being the stuff she was already good at, to fill in some of the dates and other information she was missing. We made a reporter of her, too, got her contacting friends and family and long lost acquaintances to ask for their memories. She found that the stories didn’t always mesh, and in the turbulence between this person and that, found where the heart of her own story, with its own clear perspective and bias, really was.

And week by week, though Dr. Sue became sicker and sicker, the story began to take shape, much of it news to her, thrilling for all of us who’d taken on roles as her audience.

Late in the game, her husband (also a scientist, even less a writer) began to take part, too, as she had become too ill to concentrate for long, and later to even type or hold a pencil. I worked with him on interviewing technique, also a little on editing—that task would fall to him—and also got him involved in actually telling the story from the point it became theirs and not only Dr. Sue’s. The disease moved very much faster than predicted, sadly. When she died, the project was incomplete—formerly her greatest fear, but in the end she knew her husband would carry on, finish the project. The writing, already partly his own, and already a grieving tool, became a way for him to articulate his own devastation around the death, to capture the woman in an object he could hold, could turn to, something the bereft children would have forever onward. The kids, a little older now, three and five, took part too, adding their stories as best they could, but adding something new—drawings and poems and in the end a very nice cover for the book, the finishing touch on a private object made to last.

I don’t know, it all kind of surprised me, broadened my understanding of my work as a teacher.

In another workshop I met a young women whose life had stopped cold with the death of her beloved long-term boyfriend in a car crash. Friends had urged her to take up her fiction writing again. In the one story she had managed to write since his death, nothing much at all happened. It was about a fellow who got on highway 183 in such-and-such a town and drove home after work. At home his girlfriend made him a beautiful dinner and afterwards they talked for hours while a pair of candles burned down. Most of the story, in fact, was this talk, in which the young woman told the young man all of his good qualities, all of the things she loved about him, enumerating them one by one. The young man, for his part, told of all the favorite things they’d done together. They’d had a fight that morning, was the engine of the story, supposedly.

The rest of us didn’t yet know her actual story, and urged her to make something more happen in the fictional one. She resisted, just kept working on that conversation. In the end, the something she made happen was a long, lingering kiss. A beautiful story as it turned out, and no one could quite say what made it so powerful.

But, as we would soon learn, it was what didn’t happen that powered the story: the real boyfriend, of course, had crashed and died on route 183 in such and such a town on the way home from work. The story’s boring commute home was the commute that never got finished. The story’s long conversation was the conversation the real couple had never had, that long-term couples seldom have. Our writer had used fiction to help herself through her guilt and her regret, had put form to her sorrow. Didn’t matter that the story didn’t work on the page—that wasn’t the point.

In both cases, and in many more cases in my classes over the years, the beauty of the writing is that it carries the mourner or the dying person outward rather than inward, towards people instead of toward isolation. It does this because of the implied audience, for one thing—whatever’s said must be said clearly if it’s to be read and understood. And in that clarity, perhaps, lie the seeds of healing.

“form to her sorrow”

What a lovely look at lives and words and how they intertwine.Serendipitously I came here to look away from myself and musings on the journeys of life;the implications of the ending that implies.

Two days ago I met a man out on a quiet stream,he was about my age but in a shorter ,slower, boat.He said “time is so short” and I replied”nah,life is long”before pointing out the swimming serpent near his boat.He said “I love snakes”and paddled quickly to it,picked it up and was bitten on the hand.”That hurt”he said,and posed while I composed a picture;the snake,his hand,both frozen in a frame.

I sent him the pic,he sent back a story of the ER and his worried wife.I woke before sunrise today with this poem in my head.

Journey’s End

The life he saved

Was both his own and shared

The steps between prodigy and prodigal

That everyone knew some of and that

No one outside himself would ever know completely

He gave away the parts again and again

To every corner of the wind in words

But deep within he kept the sweetest,ripest part

The way that welcome came

From faces old and familiar

When like a swallow

Diving to skim a drink from the lake

Of his history

His eyes met those of his reflection

And drinking deeply he knew both

The measure of the sky above

That horizons could not hold

And the depth of history below

From which he came,and left

And returning to saw anew

And streaking down to partake from the past

He glimpsed within the sky himself

And knew now that surface was both real

And illusion

The journey’s fruit of knowledge

Bittersweet awareness of the size and scope

That stays within the throat,

Unswallowable

Adam’s evil and good inseparable

The lump of life ineffable

That is the yawp echoing from within

Out to all ends

Of perception

OMG, Bill. I am bawling my eyes out. Not that it ever takes much. But jeez, what radiant stories from your teaching. Thanks for sharing them with us. xo