Guest contributor: Debora Black

Table For Two: Debora Black interviews Annette Berkovits

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

10 comments

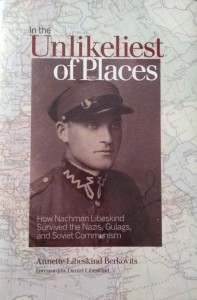

Debora: Annette, thanks so much for being here on Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour. Some day soon we must actually meet for a martini or two. But for now, a cyber setting. I thought, given the complex outcomes of the narrative you’ve written, tea and cookies by this warm fire at Three Peaks Grill would be fitting. We can watch the alpenglow spread over the ski mountain as we discuss the pages of your beautiful new book: In the Unlikeliest of Places, How Nachman Libeskind Survived the Nazis, Gulags, and Soviet Communism.

Annette: Thank you Debora. Right now, with fall upon us, tea and cookies by the fire sounds very cozy. You know, it may be an odd way to begin, but your mention of the mountains made me think of one of my first memories: the foothills of the Himalayas where I was born, purely by accident of fate. Readers of my book will discover that my parents found themselves in such a remote location because they were escaping the horrors of WWII in Poland.

Debora: Since we’ve landed on the subject of place, I must tell you that you sent me running for my atlas more than once as I tried to follow Nachman’s journey—I wanted to see it all, you know? Something in the subtle and urgent way you brought place forward.

Annette: Even with the years of research I’ve done and having actually lived in some of those places, till this day I can’t fathom how my parents made a journey of thousands of miles, by foot, by wagons, by cattle trains over terrain so remote, and some of it ravaged by war. All those exotic places! I couldn’t help but make them vivid for the readers.

Annette: Even with the years of research I’ve done and having actually lived in some of those places, till this day I can’t fathom how my parents made a journey of thousands of miles, by foot, by wagons, by cattle trains over terrain so remote, and some of it ravaged by war. All those exotic places! I couldn’t help but make them vivid for the readers.

Debora: Annette, while I waited for your book to arrive from the printer, I kept thinking about the bit of back-story that I’d already read about—your discovery of your father’s cassette tapes, which held the contents of his life on the run, in WWII. This discovery must have been quite a moment. I kept imagining that scene and you listening to all the details. I wondered what all of that must have been like for you, whether the tapes held any surprises or were the events familiar to you, and finally how the decision to write the book unfolded. You address this in the prologue of your book. It’s all so fascinating, will you describe it all for us here?

Annette: The tapes were an enormous surprise because I thought my father would rather spend his time in Florida painting and playing music. When he was first given the tape recorder he said that he had basically told me all there was to say, but it turned out he added so much detail and so much color to the story. He was usually the kind of “just the facts, ma’am,” type of storyteller, no embellishing, no making the lows, lower, or the highs, higher. So when I learned he sang on the tapes I was flabbergasted. I knew he loved to sing and had a beautiful voice, but to sing into a machine? That was so unexpected. He always loved to have an audience. After I got over the amazement I realized, “Of course! Music was his love, his language,” it had to be a component of his story.

Debora: How wonderful! And having read the book, I quite agree. I can totally see Nachman reveling in a little showmanship. Makes me smile just thinking about it. Which is a testament to your writing skills as much as it is to Nachman, himself. Another question for you about getting started. I was curious as to how you would approach the writing. What would be your authorial role—that of biographer with research and facts checking, or that of transcriber setting down the memoir recorded by your father. In fact you surprise us! Tell us about how you found your way into the material and crafted the writing

Annette: I suppose I played both of these roles, a transcriber of the tapes at first, then the biographer doing the research, but there was a third role too; that of a memoirist, telling my own piece of my father’s story. After all, no character in any memoir is “lone as a fencepost.” Everyone interacts with family members, friends and others. So, yes, I was an element of my father’s story. Debora, that phrase I just used, “lone as a fencepost” probably rings a bell. It comes from the book. It is, in my view, an amazing turn of phrase describing the solitude of an Auschwitz survivor, my father’s sister.

Debora: Yes, I do remember. From her letter, was it not.

Annette: Yes, you are correct. It was in that very first letter Nachman’s sister Rosa sent after she returned to Poland.

Debora: Were there any special or difficult considerations in the editing?

Annette: Difficult considerations in editing? You can’t be serious! Doesn’t every author run into them? For me, one of these massive boulders along the road was the transliteration from Yiddish, German, Russian and Polish. My father was fluent in all of them. Luckily I know Polish well, so that made it a hair easier, but getting the exact meaning in translating, not only transliterating, was sometimes a challenge. That fencepost phrase is one such example.

Debora: Oh, interesting, even a phrase so seemingly simple. Annette, you divided the book into sections. Tell us why you chose those particular divisions.

Annette: Yes. There are three parts to the book: Before, Purgatory and After. I think that like for many survivors of major trauma, life is divided into two radically different chapters, what happened before it and the altered life after. So that explains the first and last section. It’s the middle section—Purgatory— that may be cryptic. For the many reasons I explained in the book, my father’s discovery (while still in Kyrgyzstan) of what had happened to his immediate family, his life in communist Poland after WWII and his subsequent experiences in Israel in 1957 were so difficult they had to stand apart. They were singularly challenging in the emotional sense and the anguish, unlike anything he had experienced, even worse than the gulags.

Debora: I understand that the title of your book underwent a few changes along the way.

Annette: Can you hear me laughing? Coming up with a title is one of the most frustrating tasks for an author. It has to tell a potential reader what the book is about, or it must pique curiosity; it must serve as a marketing tool. Few authors are good at, or even enjoy marketing. And it does no good to settle on a title from the start because one doesn’t know exactly where the story will go. I did have a working title and was actually quite fond of it, but Bill, bless his heart, told me in the gentlest way possible that it may need rethinking. I liked having a working title (though in my heart of hearts I thought it would be the final title) because it made my book more real to me. It was something to hang on to, way before I had an agent or a publisher. Are you wondering what it was?

Debora: Of course!

Annette: Okay, I will spill the beans: Born in a Lucky Caul. This was something my mother often said to my father, “Nachman, you were born in a lucky caul.” For those unfamiliar with a caul, it is said to be a membrane on a newborn’s head, like a cap or a bonnet, which superstition says will protect that baby for life. Now that you’ve read the book, Debora, don’t you think it’s a decent choice of a title? The problem was that few people have any idea what a caul is. I thought that would arouse curiosity, but my publisher did not agree.

Debora: I do think it’s a good choice. The title you finally decided on, I think, is perfect. You capture so much, thematically. Annette, this is such an important book, about important people and important events. Did this weigh on you? What personal and professional trials and triumphs did you encounter while writing the book?

Annette: Yes, Debora, I am glad you asked because the responsibility to tell it not only well, but accurately, weighed on me greatly. What is more, I was extremely concerned to paint my father, actually both my parents, as real flesh and blood individuals, not one-dimensional silhouettes on a page. I worried constantly that I might inadvertently distort their point of view, or attitude toward someone or something, or put words in their mouths that they would not have said. I was obsessed with this because any distortions would be unforgivable. These individuals cannot respond and straighten out the record. I think this is a crucial responsibility of any author chronicling the lives of deceased individuals. As for triumphs, that is still a bit hard to see, but I am very gratified when people tell me things like, “I fell in love with Nachman.” Wow, making someone fall in love with a man who no longer exists makes me feel like a magician. It’s such a power.

Debora: You definitely bring Nachman off the page. He’s very charming. And Dora! What an independent spirit and a savvy entrepreneur. Annette, your pages reveal that by 1939 abhorrent discrimination and violence already have been waged against the Jews across Europe and in Poland. Then, on September 1, Germany crosses into Poland and the war arrives in Nachman’s Lodz. The related scenes are riveting—a turning point for Nachman’s entire family. Explain for us what is going on and the individual choices being made. What do you think you would have done?

Annette: I think I will take your second question, first, Debora, because that’s an easy one. The answer is: I don’t know. One can never truly know how one would respond under such traumatic circumstances. I wouldn’t believe anyone who says they know. I do think my father was prescient in his quick assessment of the situation. He remembered the German soldiers from WWI, they were soldiers then, not the beasts he saw in September 1939. He concluded very quickly it would be a death sentence to stay put. No doubt he factored in all the anti-Semitic developments across Europe in the thirties. The danger just screamed in his brain: get out! And it was an act of bravery to cross the River Bug, sneaking through a barrage of gunfire from two hostile armies on each riverbank. His relatives thought he was crazy to go. Years later he would tell me: “Ania, never be attached to material possessions. It could cost you your life.” And when you think about it, it applies to other situations, not only war. Don’t go back into a building on fire to retrieve a valuable item. Evacuate when you hear a hurricane warning, or a tornado. Hit the airplane evacuation slide when asked to, without looking for your purse.

Debora: Annette, I found this particular part of the writing to be a huge achievement—so many events and people and political ideals and conversations have been pieced together to bring us to this juncture. It’s filled with tension. Was it difficult to craft?

Annette: I assume you are speaking of the moment my father made the decision to leave, and his subsequent encounters with his sister and brothers.

Debora: Yes, exactly.

Annette: Debora, oddly, that segment was not so difficult to craft. Probably because as far as my father was concerned, his effort at persuasion was such a tragic failure. It traumatized him. He never, ever, got over his inability to convince his sisters and brothers to join him, or at the very least, his nephew Isser. Often he told me that Isser had enormous artistic talent like my brother. Since this weighed on him all his life, he told me the story time and time again. So much so, I felt as if I had actually been there with him, pleading with his relatives. I think that is what made it vivid to me as a writer and, consequently, I was able to transmit it that way to the reader.

Debora: The war ends. Describe the chaotic scene when Nachman, Dora, and Anetka (you, a toddler) finally return to Lodz.

Annette: Oh, goodness, Debora, I don’t think I can encapsulate the devastation, physical and spiritual, of returning after seven years to one’s birth city and discovering everyone you had loved was murdered and your home occupied by strangers. And there you are with a newborn who is very ill, a wife who is a physical and emotional wreck and you have no money, no place to live, and no job. Even now, it boggles my mind how my parents mustered the inner resources to move on with their lives and raise two babies.

Debora: Tell us about your brother, Daniel Libeskind.

Annette: Well, it may not be fair for a sister to speak of her only sibling, as a “starchitect.” You must know that some inadvertent bias may creep in. But, since you asked, I think Daniel has very much inherited my father’s sense of optimism. He rarely gets stressed out. You might have read how many people, the various stakeholders in the process of planning rebuilding of Ground Zero in New York, have been at times aggravated, or frustrated with the complexity of the process. Guess who was never annoyed by it? Daniel. He always says, “That is the nature of the public process in a democracy. Let it take place and things will work out in the end.” I will tell you something else that few people know about Daniel: he is a musician. Music means as much to him as to our father. He not only designed the stage sets and costumes for the Deutsche Oper Berlin production of St. Francis of Assisi, he did the musical direction! It’s a 3-hour opera and I attended its premiere. Daniel is also a wonderful artist. Exhibitions of his drawings attract large crowds. And unlike most architects he does not use a computer. He draws by hand and makes physical models of his startling buildings. Now that’s a true Renaissance man.

Debora: Your father describes events that make-up your childhood in a war ravaged setting. What do you remember thinking and feeling about your existence?

Annette: I remember the closeness of our small family. We had no one else but the four of us, like a small ship floating on an ocean. Until my father explained to me what had happened to our family, and he did that while I was fairly young, I always wanted to know why my friends had grandparents and cousins, but we didn’t. Why they had photo albums full of family members, but we didn’t. Why we spent so much time visiting the cemetery. Why we sometimes had to speak in whispers. Why the boys in the courtyard called us names. Why my mother obsessed if I didn’t want to eat. I explore these feelings in much more depth in another manuscript, focusing on my coming of age. Maybe it’ll get published one of these days.

Debora: I certainly hope it does. I sense from the pages of In the Unlikeliest of Places that the transformation from Anetka to Ania to Annette is a powerful one. Since you are a person who has seen a few things, I can’t help but wonder what you believe about our current world. Can you sort out anything for us in regard to that hot zone where culture, religion, politics, and environment collide?

Annette: Oh, my goodness, Debora! The answer for this kind of question could easily fill several volumes. Of course, these elements are interacting with one another constantly, even when we are not looking. Of the four variables you cited that can inflame a “hot zone,” I think religion is the most incendiary. Culture seems to mutate over time and politics are often reactive to a particular set of circumstances, but religion for “true” believers is immutable, least subject to reason, or to compromises. I won’t comment about environment because it can be physical, such as lack of water that can lead to conflicts, or a charged political sphere that is a medium for unrest, so it’s far too complex to delve into here.

Debora: The Soviet Union (Kyrgyzstan), Poland, Israel, the United States. These are the places of your life. What does Home mean to you and which do you feel is yours?

Annette: That is a very interesting question, Debora, and one over which I had some heated discussions with my son. He once asked me this very question and was quite upset that I wasn’t sure where “home” is. “Mom, you are an American! How can you not know?” he asked. But it’s still true. Even though I have lived very happily, I might add, in the US since the early sixties, I have a residue of a displaced person’s feeling. I can tear up on hearing a Russian song, probably because my father was so grateful for the “shelter” there (if you can call a Gulag that) and he learned so many beautiful Russian songs. In my mind these songs merge with the crimson fields of poppies in the Fergana Valley where I was born, and I get very nostalgic. Then there is my intense love of Israel, not today’s Israel, but the young, vibrant Israel in the decade after its formation. Poland is the one place that evokes very conflicted feelings. I am fluent in the language and hearing it makes me long for my mother who spoke it most of the time. It is connected with some positive childhood memories, like my Polish nanny Marysia, whom I loved and the beautiful multicolored sweaters she knitted for me and the A’s I got in school. But then there are memories of ugly anti-Semitic incidents too, so it’s a very mixed bag. Then there is America, the place I found the love of my life, gave birth to my very American children and learned the language in which I love to write, so? I guess, if push came to shove, I’d have to say America and yet….

Debora: Clearly your father’s life inspired you. But there is also your very notable career with the Bronx Zoo and the Wildlife Conservation Society, spanning some thirty years and replete with accolades and awards. And now, author. Do you take away any lessons from these experiences that you value in particular, or that you believe make you wiser or in some way an even better person?

Annette: First, I wouldn’t say any of these experiences made me wiser. The more I know, the more I realize how much I don’t know. In this world of information explosion we still cannot consider ourselves truly wise because it’s not just information that is required for wisdom. One needs time to integrate what is known, to internalize it, to think, analyze, compare, contrast and who has the luxury of time in this lightning speed world? I don’t. I can tell you that as a result of my wildlife conservation work I have learned to treasure animals and plants in all their magnificent incarnations. I have a strong awareness of the tragedy of extinction and the role of humans in accelerating it. I suppose that in some ways the history of my family has made me appreciate life even more. Watching young animals born at the zoo was so life affirming and so far removed from the dark years. It may be the reason why I stuck so long with my career. Then my husband persuaded me to retire so I could write. “It’ll make you happy,” he said convincingly. And he was right.

Debora: How will you continue from here? What’s next?

Annette: I have so many ideas I’d love to put on a page, Debora. Sometimes I am torn between writing poetry, which I enjoy tremendously, or writing a novel which is a whole other challenge. Oddly, I find that each genre requires a totally different mindset, so on days (or weeks) when I am writing poetry I cannot write even one novelistic type sentence. I need to reprogram my brain to write the novel I’ve begun. Then the work required to publish, or to promote one’s work requires still a completely different skill set. I have two completed nonfiction manuscripts I’d like to have published. One of these is a memoir of my critical growing up years and my relationship with Daniel and my parents, the other is a collection of wild and crazy stories based on my work life. That one has a memoir-like component of a woman making her way in what was essentially a man’s world. And strange as it may sound I’d like to write a play one day. Oh, goodness, now that I’ve said it my friends may call me to account. “So, is your novel published yet? What about your play?” Divulging my authorial aspirations is a risk, but then writing is all about risk.

Debora: Annette it has been my great pleasure to speak with you about, In the Unlikeliest of Places, How Nachman Libeskind Survived the Nazis, Gulags, and Soviet Communism

Before we end, could you tell us a little bit about your publisher and where we can find out more about you. Also, where do you like to send people to purchase your book?

Annette: My publisher, Wilfrid Laurier University Press in Canada was founded in 1974 and publishes 35 titles a year in genres ranging from history to literature, women’s studies and a number of others, including life writing, the area in which my book falls. I love their motto, “Transforming Ideas.” Isn’t that what good books do: change our way of thinking about the world

Annette’s book is available from a number of sources.

From the publisher directly: http://www.wlupress.wlu.ca/Catalog/berkovits.shtml From on-line sources such as Amazon.com: http://www.amazon.com/In-Unlikeliest-Places-Libeskind-Communism/dp/product-description/1771120665/ref=dp_proddesc_0?ie=UTF8&n=283155&s=books Or from Barnes&Noble.com: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/in-the-unlikeliest-of-places-annette-libeskind-berkovits/1120006016?ean=978177112066

And of course from your local independent bookstore.

Annette’s website, which offers excerpts from the book and her public reading schedule http://unlikeliestofplaces.wordpress.com

Debora Black is a writer living in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

Sometimes you think you’ve heard everything there is to hear about the holocaust and the other disasters of World War II, and then a book like this comes along! Great interview, Ms. Black. And great discussion, Ms. Berkovits!

Even though a great deal has been written about the Holocaust it will never be enough because for every person who perished, or survived, the story is different. What I think helps readers make sense of such a tragedy is to hear individual stories. One simply can’t get one’s mind around numbers in the millions.

What a compelling interview of a fascinating woman. Looking forward to reading the book.

Thanks, Susie. Do let me know if if have any questions after you have a chance to read the book.

What a wonderful interview Annette. I can’t wait to read your book. I’ll have to thank Jessica for sending me the link. My sister Nancy used to work at the zoo and we both knew Jessica at Mamoroneck High School. You probably don’t remember me, but We met in Larchmont many years ago. Congratulations.

I do remember you Philip. Who could forget a man so creative as to invent a Halloween costume only a woman of a certain age could recognize? After so many years you might have forgotten it yourself.

I do hope you enjoy the book and I use “enjoy” with caution as some of the content is emotionally difficult.

Thanks for introducing me to this book, Debora. It sounds like an incredible story. Can’t wait to read it!

So nice to discover I’ll have another reader as a result of this interview. I hope you’ll enjoy it, Tina.

Wonderful interview. This book is on my “next to read” list. Born as a first generation American, from a family that was also caught up in the war, it’s difficult for me to imagine what so many families went through. Looking forward to going on this journey with Annette’s extraordinary family.

Hi Stephan:

I do believe that there are certain characteristics shared by families touched by war. My father’s journey was tough, but in the end, triumphant. He never lost his sense of optimism. It’s what kept him alive. I do hope you’ll find his optimism infectious.