Table for Two: An Interview with Lea Graham

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

1 comment

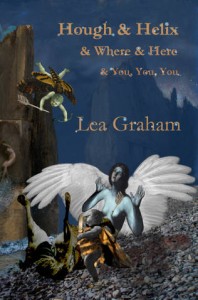

Lea Graham is a traveler. Fluent in Spanish, and a poet to reckon with, she also speaks wine. Her first book of poems, Hough and Helix, has just been published by No Tell books, and it is a wonder, a confluence of image and story and meaning and mood. I first met Lea in Worcester, Massachusetts when we were both teaching there (she at Clark, I at Holy Cross), and we had meals together from time to time and good conversation. So this “Table for Two” isn’t entirely a fantasy, though we’ll make free with the location:

Lea, in answer to my query: “A beach in Cadiz (the oldest Western city, you know, because of the Phoenician trade route, I believe). We’ll eat tortitas de camarones (small thin crispy omlettes with tiny prawns), calamares en su tinta (squid in its ink), all kinds of shellfish including sea urchin, crab and lobster…

BR: And to drink?

LG: A bottle of Albariño. It is white wine from Galicia and very refreshing!

(A man in a white shirt arrives carrying a basket full of the very foods Lea has mentioned, and a slightly chilled bottle of the exact wine. He and Lea chat in rather formal Spanish without a glance at me, while he pulls an ingenious folding table from his basket, sets it up low in front of us, snaps a tablecloth in place, produces good glassware, real silverware, linen napkins, and then he lays out the food: freshly caught, freshly cooked. Very carefully, he pours us tastes of the wine. Lea likes it, nods. I nod too—it’s crisp, cool and exactly what you want to drink on the beach. He fills our glasses. When he’s done he retreats to an attentive spot behind us. We toast, we drink, we look out over the Bay of Cadiz and the great Atlantic Ocean. Somewhere down the beach there are a couple of young men playing guitars. At first, it sounds like traditional flamenco-inspired music, then Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face.” An older woman with pink-tinted hair and her small terrier trot by us. We are reminded that even in the oldest part of the old and formal world, the new and transient are never far away. The wine is nice, very, nicer with every sip.

BR (ready with his fork, hoping for a long answer): Tell us about the genesis of your new book, Hough and Helix & Where and Here & You, You, You.

LG: The book started as a confluence of several things. I was re-reading Anne Carson’s Eros: The Bittersweet and thinking of the way that desire was written as a kind of space. Since I’m really interested in “place” and all that accompanies it, I was immediately caught by how this abstract notion was figured in “reach” or “edges,” etc. I was thinking…

BR: Reach? Edges?

LG: Well, the notion of “crush” and the geography that makes it possible were the things I was interested in. Most of the poems have little to do with any kind of satisfaction or culmination. So, yes, “reach” is the action where all happens—where our imagination happens. Not “touch” or “receive.” “Edges” are precarious places and also a place of curiosity and mystery. Also, this works for the destructive notions of “crush,” too. “Reach” embodies a longing and lack. When you’re “on the edge,” it is a place of potential destruction.

BR (tasting the tortitas, long sigh): Thanks.

BR (tasting the tortitas, long sigh): Thanks.

LG: So. I was thinking about how music (Miles Davis, James Brown) and weather influence the state of being—either as despair or as the imagination that accompanies desire, hence, “crush,” as in having a crush. I was also watching a lot of Jim Jarmusch films and thinking about how he manages to suspend scenes in silence. Those seemed like the space of eros to me. A couple of scenes in the film Stranger than Paradise come to mind. There is at least one scene (and maybe more, I can’t quite recall now), in which the characters are sitting around in a kitchen and no one is speaking. Jarmusch lets that scene go so long in silence, just ending it before it loses all tension. It’s pretty fascinating and I always compare it with the way as kids we would take our chewed gum and try to stretch it as far as we could before it broke into a whispy string. The other scene that I think about all of the time is when the three characters are driving to Florida in the middle of the night. The young woman keeps playing Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ version of “I Put a Spell on You” the whole time. It’s night and they’re driving and listening and saying very little—and the song keeps starting over and over again. I think it’s a place and moment that I want to stay in. Who cares about arriving? Stay in the car with Screamin’ Jay and the open road at night and all possibilities before you.

BR: Nice.

LG: Anyway, I began simply writing poems with a number attached to the title “Crush,” so, like “Crush Number 137.” This was influenced by a brief connection with a former classmate of mine, who wrote “First Love” poems that were numbered. I thought that was so clever (thanks, Nicole!), and decided to steal that format and see where it took me.

BR: I love the crush figure, all the ways you fold and re-fold it, all the meaning you squeeze from it, never forgetting the desire angle, the original inspiration.

LG (tasting the squid, which is divine, lubricious and salty and heavy on the garlic): Yes, well that re-folding and folding business was tricky and I think one of the reasons the book seemed to take a long time. I needed room to breathe between writing sections or movements of it. I mean it’s desire and it’s destruction! What more is there to say?

BR: (long pause over the wine) Could you say more?

LG: Real funny, Roorbach.

(The young guys down the beach stop playing for a moment and start to laugh.)

BR: But I’m serious.

LG: Hm. The nice thing about hitting the very predictable walls that you might imagine, is that I quickly tired of mining my own experience and what seemed foundational texts (The Meaning of Aphrodite and Sappho, for instance) and started to get crazier. Everything became fair game: Big Punisher; Childe Hassam’s painting “Big Ben”; Bywater’s disease; the Hundred Years’ War; Swahili phrases; The Craft of Research; the final blog entry of the poet Reginald Shepherd; etc. Even when I “cannibalized my own experience,” as Phil Levine has called it, I pulled in pre-teen girls talking Smallville with sea turtles on a Costa Rican beach. I wanted to see how many diverse and divergent materials I could get into the poems and how far I could stretch notions of desire/destruction—again, like that piece of chewing gum—before they would break. I wanted to give body to crush.

BR: And you have succeeded.

LG: Thank you.

(They eat as the music down the beach starts up again. There’s a small crowd of teenagers hanging around, smoking cigarettes, drinking beers. The sun is falling. It’s easy to imagine the Phoenician sailors gliding into this bay…. The wine pulls it all into the clearest possible focus, a kind of lens.)

BR: It’s clear from the poems that you are an eclectic reader and a collector of phrases and words and objects and people—what’s your method for gathering all this material? And how does it make the leap from experience to poetry?

LG: I often think about the experience of reading as personal or lived experience. Perhaps it’s not the same overwhelming sensory event as running away from a wild elephant under a full moon in Tsavo East at midnight, but it is still an experience that stays with me as I think it does for most writers. It’s hard to say exactly about how I go about collecting, but I like to let my curiosity guide me from one text to another. With that said, I also have an organized reading list when I’m working on a project.

BR: I remember that elephant story.

LG: I told you that one, huh? Ah…I thought I had saved it! Well, then you’ll remember that the moon caught the elephant’s tusks and glowed. If I hadn’t been with two of my friends (who don’t write fictional texts), I would have doubted myself on that detail.

LG: I told you that one, huh? Ah…I thought I had saved it! Well, then you’ll remember that the moon caught the elephant’s tusks and glowed. If I hadn’t been with two of my friends (who don’t write fictional texts), I would have doubted myself on that detail.

BR: Let me read you one of your poems, “A Crush before the Sexual Revolution.”

LG: No, I’ll just say it:

Now that I’m old this cold freezes the quarter notes of my thought.

Memory’s just a jacklight of once. I used to hide wings & eggs,

damaged things, in a crawl space beneath the house. Colors lived in my eyes

as rejection. I stowed a pocket watch & buckeyes beneath

a sycamore, the clouds of Worcester. My favorite word:

mercurial. I’ve been summoned through Pig Alley, scanned lavender

fields on the Isle of Wight. I spied a neighbor girl peeing

a ditch when I was ten. Her skirt’s hitch & crooked mouth survive.

It’s like a hummingbird’s quicksilver jab to a red vest.

These are bones in my soup, nevertheless. My father danced

a gimpy box step. My mother stole apples from Kunitz’s

tree. One May, I photographed Priscilla in gingham & pearls.

She sang “sugar, cause sugar never was so sweet.” At the edge

of Bell Pond. At the edge of Bell Pond. Later that summer she

beaded her thighs with my initials. She carved them there.

BR: I hear music here.

LG: Thanks. That poem took years to write because I kept trying to avoid the speaker, but once I could hear the voice, it fell into place. You know, I grew up memorizing Bible verses from the King James and also listening to Southern preachers. That’s the genesis of the music, I suppose. I almost don’t like to talk about this because I sound like a walking Southern cliché. I might throw that back at you…. How do you, a guy who “used to play in bands,” incorporate music into the writing?

BR: It’s in the sentences. It’s a rhythm. I don’t actually do it on purpose—but when I’m reading aloud, reading to an audience, I’ll often realize I’m tapping my foot. I always loved those beat recordings of

, like, Gregory Corso reading with a bongo player and a saxophone. Though I’m no beat poet. There’s another music, too, when things are going right, something big humming, almost groaning, that thing I used to hear lying in bed as a kid and thought was the world turning.

LG: Wow…the “world turning.” When I was really young my mom always had us taking naps. I was always fascinated with the sound of my heartbeat which seemed to be coming from my ears. I imagined there was a hammer inside of me. So yes…the “world turning” is right on and lovely—and quite a bit more romantic than my hammer!

BR: Hammers have their place. Can you say “Crushed Psalms”?

LG: “Crushed Psalms.”

Oh… you want a recitation? Ok, here goes….

Let us gown the red shower curtain

Let us eight track the gospel

Let us double modal & apocopate

Let us tump & perfoliate

Let us call the hogs to scattered examples of fair dialect

As cowbrute so whickerbill

As winter water so skillet tea

Let us climb the tower for a dime & pie

Let us fry the grindle, pickle the gar

Let bone from water & roads of cullet

Let three deep & no lack of corky protrusion

Let K-Tel present the Everley Brothers

Let us “Dream, Dream, Dream”

Let Pistol Gunn come to town,

his Dentyne & gold incisor, his white patent leather.

Let not the girdle nor the mouth of soap

Let us praise Tang & curlers at noon

Let us gin our Dixies

Let us cuss from innocence

As we hymn so shall we holler

As we panicle so shall we spike

Let us impeach our mouths

Let the long “S” of her hair

Let stickers bush & ass pie

May she pull up in her mama’s Impala, smoking Camels

May we be thirteen, an empty house

Let us eulogize the candy bars of Piggly Wiggly

Let us sit under the toothache tree with the prom king of poetry

Let “Arkansas Snap”

Let that dog hunt

Let us decoupage Jesus at the door

Let us to the five points of Calvinism

Let not the heat, but humidity’s sweet flank

Let Frank Stanford’s eyes “shine for twenty dollar shoes…like possum brains on the good road”

Let finger bones of Pea Ridge trumpet honeysuckle

Let the Hard-shelled Baptists we’ve loved before

Let us belly bob wire, escape by hoopsnake

May there be a bed of devil’s food & Seven-up cake

May we kick the can of death

May we walk perimeters of a dare

May this geography guard our going out & our coming in

May all our days reckon & give ear

May the dogwood in April forever, amen

BR: Tump and Perfoliate?!

LG: Well, “tump” is one of my all-time favorite words! The reason is that it is a word from my childhood, and if my uncle Jim Pat is to be believed (and I think he’s the one who told me this), it is indigenous to the NW Arkansas/SE Oklahoma region. It is a combination of “tip” and “bump.” We used it especially when we would turn a rowboat over to drain the water out: “Just tump it.” I love the physical sense of the word both in meaning and sound—and that it’s a part of the place where I grew up.

BR (Drinking as the sun hits the horizon): Tump, everyone. (The growing crowd of teenagers insouciant in their skinny jeans and t-shirts begin to dance near a fire that we’ve just noticed. Vendors with baskets stroll at day’s end trying to sell the last of their figs, popcorn, cold beers—one of them even carries a giant chocolate Jesus.) Perfoliate!

LG: Yes, it’s the way the stem passes through the leaves on certain plants—like a honeysuckle. I love the botany words. Also, remember that most of my family members work in medicine or as scientists and almost all of my grandparents were farmers so, perhaps, that love of language from the natural world is inherited in some ways.

BR: Michael Anania has been a mentor and inspiration….

LG: Well, Michael Anania has been a great teacher and mentor to many poets. I count him and his wife, Joanne, as dear friends. I think there are two particular things that I feel very fortunate about in working with him. First, he has always been a teacher that encouraged a great range of writers and writing. He gave many of us permissions to do what we were doing, rather than turn ourselves into whatever the poet du jour was—or to emulate him and the type of work he does. Secondly, he and I share a serious interest in place. He really helped me to explore the stratigraphical layers of my places—and validated those places that I thought might not belong in poems. He and I always talk about the avocado seed that is suspended in water in an old jar on the windowsill of farm kitchens.

BR: There’s one on my kitchen windowsill right now!

LG: Anyway, he gave me permission to value those early images and my own mythology. Also, reading and teaching his work keeps giving. I have been teaching his poem, “Steal Away,” this week. It’s focused on the neighborhood in Chicago where Chess Records was located and where so many Blues men and jazzmen played and died. The layers of that poem with its “coils and rails” of Chicago’s El, the movement and heft of memory and proper names, the suggestion of narratives like the remnants of the plastered Superfly poster is simply marvelous. Michael was a great teacher for me, and is now a friend and has always been a poet I admire and teach.

BR: Literary careers fascinate me. Yours is a work in progress, of course, but with this book I see such an impressive leap. I read many of these poems in draft and loved them, but here, you’ve revised and re-imagined and re-folded them so beautifully it’s as if a new angel had begun to sing to you.

LG: Well, I wish I had a groovy reason for this leap, as you put it, but I think it is pretty simple. I believe there were two things that helped significantly. First, the time it took to finish the book was a good thing. I know I’ve been criticized by fellow writers for taking too long with this first book, and I have been self-critical in the past about it, too, but now I’m really glad that it took as long as it did. I got to add and subtract in the last two years before it came out in a way I’m really proud of. That helped me to springboard out from the earlier Anne Carson (et al) materials and get looser (even though the book has been called a “relentless kneading”!) Secondly, I give credit to my editor, Jill Alexander Essbaum. She helped me to see what I was doing (or overdoing, at times) more clearly. I will say that after having spent so many years into workshop, I wouldn’t have thought that a good editor could make so much difference, but, at least with Jill, it did. I know as writers we’re supposed to be sure of ourselves and even arrogant about what we’re doing. I would say that I am those things (hopefully, in a charming way), but I have seen how another pair of well-trained eyes can help immensely.

BR: I adore my editors. Unless I hate them. How has the academic thing fit in? The need to make money?

LG: I get asked this question a lot by my students and I always worry a little because my answer— the path that I took post-undergrad years—might not be very helpful to those trying to figure out how to work as a writer and/or a college professor now. I think the world and the feel of the academy have changed rather dramatically in the last ten years (but this might also have to do with where I’m at in my own life…or maybe both?). Also, I know that a lot of young people starting out are worried about what their families require of them. For this reason, I think my path isn’t such a comforting one. In any case, I worked a lot of different jobs in my 20s before I began graduate school. I was a political advocate for a few non-profits working on Central American issues—namely El Salvador and Guatemala. I worked  briefly in a homeless shelter and in inner-city youth centers. I did all kinds of temp jobs. Even when I went to grad school, I was still waitressing and bartending along with my teaching assistantship. So I worked solidly for six years before graduate school and then another six or seven during graduate school at other jobs besides those in academia. Once I finished my Ph.D., I taught as an adjunct at three other institutions along with the Clemente Course for the Humanities through Bard College for another five years before I was hired as a tenure-tracked professor. There’s so much luck involved with teaching careers—even with hard work. I will say that while this path was certainly a sweaty one, in many ways, I wouldn’t trade it because of the range of experiences it has given me.

briefly in a homeless shelter and in inner-city youth centers. I did all kinds of temp jobs. Even when I went to grad school, I was still waitressing and bartending along with my teaching assistantship. So I worked solidly for six years before graduate school and then another six or seven during graduate school at other jobs besides those in academia. Once I finished my Ph.D., I taught as an adjunct at three other institutions along with the Clemente Course for the Humanities through Bard College for another five years before I was hired as a tenure-tracked professor. There’s so much luck involved with teaching careers—even with hard work. I will say that while this path was certainly a sweaty one, in many ways, I wouldn’t trade it because of the range of experiences it has given me.

BR: Including the hard knocks.

LG: I guess what I’ll also say to those who want to be writers: You can write while you work at almost anything. I don’t think that I necessarily have more time to write now that I have a full-time job in academia. The time to prepare for and teach classes, run academic programs, and to work in a department and for an institution is busier than it appears. (Actually, I blame my own undergrad profs for making this profession seem so effortless. We laugh about that now!) To pass on the great advice that Sherod Santos gave me years ago: If poetry (or writing in general) is important to you, you’ll get back to it. I would add to that and say that you don’t have to “go away” from writing. You can keep doing it no matter what your monied work is. It’s fun to get to teach writing on a daily basis, but that doesn’t necessarily legitimize me as a writer. I know some of my poet colleagues would say that it probably makes me more boring! I would encourage writers to slow down and figure out how to keep writing (and reading) alongside whatever they do to earn their physical sustenance. Don’t worry so much about rushing to publication or immediately entering MFA or PhD programs in writing. Those things are great, but I think that to be a really solid and thoughtful artist, it’s necessary to work at your craft apart from, or at least not driven by “credentials.” I know that this is counter to everything we hear and feel in a society that values immediacy and that asks for more and more accreditation. I know that I struggle to work out that balance between making my art public and working steadily, healthfully, and satisfyingly in private— towards my own standards.

BR (Slowly, and watching the ocean as Lea opens a second bottle of the wine): Speaking of standards, a favorite poem of mine is “Bridge Jumping/ W4M / Poughkeepsie (The Walkway).” Can you say something about the prose poem in general, and about this poem in particular?

LG: Funny you should ask about that since I’m in the process of writing a whole lot more prose (or prosier) poems for this next book. I like the no fuss no muss of the prose poem. It feels to me like you can pack it with “stuff”—like an ungainly suitcase with all your favorite things. You don’t have to worry so much what it looks like. I am also finding it to be well suited to the epistolary poem, as I’m working on a series of them right now. With that said, I think it’s easy to commit errors that you might not if you were more attentive to line breaks. I always try to air out my prose poems to see if that’s what I really want as a form and to see if there is content that shouldn’t be there. “Bridge Jumping…” was an assignment given by Brett Fletcher Laurer, a poet who runs a blog called Ships that Pass. It’s a blog that runs “fake missed connections”—the kind that you can read on Craig’s List. I had to go and read a lot of these, along with the other poets’ fake versions, to get a sense of how it worked, but it was a blast! It is a write-in on Craig’s List where you can address someone you have seen in passing and thought you had a connection with. I thought it was perfect for the crushes because it is the briefest of sightings. Still, enough energy and imagination was there to make you want to write the person.

BR: They used to have ads like that on the back page of the Village Voice: “You: Brown sweater and big eyebrows on the A Train to Canarsie. Me: Reading Dharma Bums and crying. You said, I could love a man like you.” Do the line lengths of a prose poem matter as they appear in the book? Or does the poem work as prose works, fitting the page on the page’s terms?

LG: If I remember correctly, this poem mostly broke where it broke (although there was a lot of taking out/putting back in and all of the usual work that revision is). There were other poems in which the page was a hindrance. I had to re-break lines to make them shorter since the page wasn’t wide enough for them. It was a strange experience having a page push me and my choices around. It was the difference between individual poem writing and book making, I suppose. I’m wondering if you as a prose writer have to think about the spatial/structural parameters as you write an individual story or essay, and then again, when you write or put together a book?

BR: Definitely, but not in such minute matters as line breaks. More in where recreated documents are placed and broken, or where a chapter breaks. You want all the chapters to open on a right-hand page, for example. Can you say the poem?

LG: “Bridge Jumping…”

You smelled of burning maps, smirked as to let slip the dogs of war. Not the stale slate windbreaker & steel-cut oats above the Hudson. I was whistling “Wake Up, Little Susie” & wearing a huipil. Your crow’s feet, tasseographical signs for journey of hindrance, diploma . The conversation went like giraffes fighting: How do you behead a poem like a horse? Why is the “ch” silent in “chthonic”? I refused your urge to push the mental health button, see what might appear: pair of falcons, oil cymes between trains, a child in a tiara. I told you the death rate was 1180 for every 1200 jumps, including Kid Courage. I told you in Hong Kong it’s the most popular form. You said falling from this height blows your clothes off, denies the senses. You wondered what happened to the 20 who got away? Cross-winds, a unicycle & my Mets cap divided factors. But I keep thinking of you like Colomb & Williams thought of Wayne C. Booth, writing his voice into the third edition of The Craft of Research years after he died. I imagine you might fish endangered sturgeon & dream of Guernica on Thursdays. If so, write to me. We could go to sea in a sieve, double the blind, buck your tiger, bell my cat, leap this dark—

You smelled of burning maps, smirked as to let slip the dogs of war. Not the stale slate windbreaker & steel-cut oats above the Hudson. I was whistling “Wake Up, Little Susie” & wearing a huipil. Your crow’s feet, tasseographical signs for journey of hindrance, diploma . The conversation went like giraffes fighting: How do you behead a poem like a horse? Why is the “ch” silent in “chthonic”? I refused your urge to push the mental health button, see what might appear: pair of falcons, oil cymes between trains, a child in a tiara. I told you the death rate was 1180 for every 1200 jumps, including Kid Courage. I told you in Hong Kong it’s the most popular form. You said falling from this height blows your clothes off, denies the senses. You wondered what happened to the 20 who got away? Cross-winds, a unicycle & my Mets cap divided factors. But I keep thinking of you like Colomb & Williams thought of Wayne C. Booth, writing his voice into the third edition of The Craft of Research years after he died. I imagine you might fish endangered sturgeon & dream of Guernica on Thursdays. If so, write to me. We could go to sea in a sieve, double the blind, buck your tiger, bell my cat, leap this dark—

BR: Do you mind teasing out the references here, or is that too much to ask?

LG: It’s my pleasure. Actually, one of the things that simultaneously flatters and irritates me is that some audiences have thought this was an actual experience. As I said, it was an assignment. What is actual is that I live near and walk on the Mid-Hudson Pedestrian Bridge pretty often. So I’m always looking at the different details of the bridge and the water. I ended up doing a lot of reading about suicide by jumping because I had seen the mental health button on that bridge. I kept thinking about how jumping from such a height would impact a person. (So is it a romantic crush or a destructive crush?) I learned all sorts of things, but maybe the most interesting information made it into the poem? In any case, I wanted to see how many different kinds of materials I could get into the poem…so I use a line from Julius Ceasar and reference a “huipil,” the Mayan smock-blouse that is heavily embroidered and usually, quite bright, and which has both cultural and political value in Guatemala. I don’t know… I was just having fun with the Everly Brothers and The Craft of Research and whatever else I was reading at the time or could think of. I like the circus of the poem. In fact, that aspect for me is the poem—not the “missed connection.” That’s probably disappointing because everyone wants a little gossip or a little romance, but it just ain’t happenin’ in this poem beyond the assignment. Although, I hope it gets people to write their own missed connections!

(A camel train is trundling down the beach, men with long sabers and longer mustaches at its head, hundreds of animals, jingling bells, the cries of drovers, belly dancers on elephants)

BR: My ride is here.

LG: Well, it’s been very nice talking.

BR: May I take the rest of this bottle of wine?

LG: There’s but a sip. (she pours what’s left into our two glasses, and we toast, throw back the last drops.)

BR (climbing onto the back of a elephant with the help of the camel drovers, who are impatient. He shouts): Could you leave me with a poem?

LG (declaiming as the young guitarists come to stand around her, gentle strains at sunset):

“Crush Starting with a Line by Jack Gilbert

Desire perishes because it tries to be love

& so, I think, why search or seek it? Entering

its way out the backdoor, calling as Narcissus

himself, curious to himself only—only

this echo. Yet, some days wild turkeys wing clumsy

across windshields, or poets come to town

& language flocks before flying south, before

jubilee, before hush & slack. In chance,

what we flush from beech & oak, or her flush blooming

at a table, remains, persists as flight, or flown:

trace of bird in my eye, balloon drift among sky,

proposing hand, arm. What is not sexual, though

sex is part, catches life en theos. Not love, but its

roaming kin & nonetheless, wonderful alone.

What an amazing interview, from start to finish. I didn’t know Lea’s work so I’m hugely grateful for the introduction to it; I’ll explore more with gratitude. The musings on writing craft and life are so rich as well, and of course Bill’s Groucho Marx-esque questions adds the perfect festive touch. (That’s a horribly awkward and ugly construction, but “Bill’s Marxian questions” obviously doesn’t work, and since it’s Monday prior to my second cup of coffee my brain refuses to come up with something else). Let me add as well that know I have a new life goal: I want to have fantasies that involve “lubricious” wines. Anyway, thanks to you both.