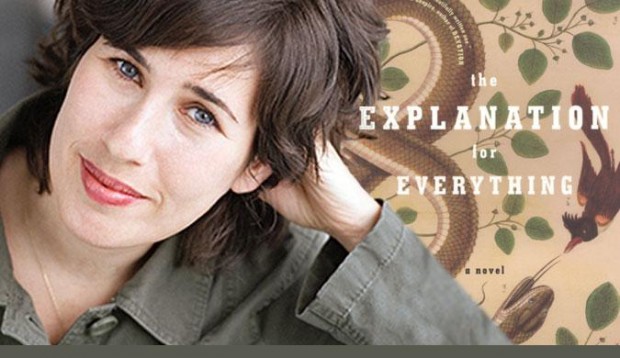

Table for Two: An Interview with Lauren Grodstein

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

Comments Off on Table for Two: An Interview with Lauren Grodstein

Bill: If we could meet anywhere we wanted for a meal and a talk about your book, where would it be?

Lauren: If we could go anywhere to talk about my book, I think we’d go to my grandmother’s kitchen in the Bronx. Now, it’s possible I’m just saying that because it’s Jewish holiday season and I’m feeling nostalgic – my grandparents have been gone for seven years, and I haven’t been to the Bronx in almost as long. But if we were at her house, at her table, she’d keep bringing us food (whether we liked it or not), and it would all be delicious: gefilte fish she’d ground with her own hands, matzah ball soup, jars of canned black olives because she knows I love them. We’d tell her to sit and eat, but she wouldn’t. The food would keep coming: roast chicken or pepper steak or brisket with the kinds of vegetables that have gone all limp and gravy-logged. Kasha. We could talk about my book a little; it’s about Darwin and intelligent design and love and grief. But let’s say you happened to be a Creationist and I happened to be an Atheist and the discussion got heated – that’s when my grandmother would bring out the sweet cheese blintzes. And we’d forget whatever it was that we were arguing about and when we came up for air, we’d agree that there couldn’t be a sweeter place on earth than my grandmother’s table.

Bill: I love that we’re having dinner at your Grandma’s.

Lauren: My grandmother was very short, with short steely hair that still had some brown in it, big, watery blue eyes, and age spots on her face. Dry lips. She wore a lot of housedresses, which are like flowered hospital gowns but without the open-air backs. When she went out of the house she wore clothes she bought off the Macy’s sale rack. She wasn’t pretty and probably never had been too pretty but she just radiated warmth and safety (to me). (To other people I think she radiated a weird kind of nervous energy). But to me – I just loved her so much. She was hit by a car and killed when she was crossing the street on the last snowy day in March in 2006. My sister was pregnant with her first great grandchild. I’d been sitting in a faculty meeting in New Jersey.

Bill: My mom died in April 2006. Ah, well. Life and life again.

Lauren: Argh, the sadness! Well, it’s okay to be sad sometimes

Grandma: Maybe yes, maybe no. Why the long faces? Eat!

Bill (stuffing face with kasha): You are great at dialogue, I notice. The book starts off with a wonderful exchange between two mutually attractive people in the emergency room, both with medical or at least biological training. Tell us about talk as a tool of the novelist’s trade.

Lauren: Yes, let’s talk about dialogue. Dialogue often feels like it’s being whispered to me by the characters – I rarely pause to consider it; I just write the next line as if I’m channeling it. I think I have an ear for dialogue because, despite the many reasons not to, in general I really like people. I like listening to them, I like hearing the different ways they phrase things. I like accents. I like the myriad ways they ignore each other. And although I’m a big talker if I need to be, most of the time I’d much rather listen than talk. So when it’s time to write dialogue, which, when I write, it usually is, I let my fingers fly. I end up, usually, with pages and pages of chatter, then I go back and edit it down a lot. If I didn’t, my books would read like the world’s longest and most inane cocktail party.

Bill: I wrote a paper for physics in college about god and science to rescue my grade after I got a 40 on the midterm exam. Without, I hope, giving anything away, I think I can reveal that your protagonist, a very appealing widower and dad and biologist just 40 years old, teaches a class nicknamed “There is no God.” And he’s very much in control of the discussion till a student comes in to ask him to advise an independent study in which she hopes to prove–scientifically–that Intelligent Design is real. He scoffs, he tries to say no, but in the end he takes her on. As a reader, I felt the elements of a storm had gathered nicely. As a mystical atheist, I worried that this kid was going to shatter my cosmic view. As a former professor, I knew he was in for a lot of uncompensated work. Did you set out on a path of philosophical inquiry, or did your characters take you there? And where did they take you?

Grandma: Physics, so fancy.

Lauren: I really like it when novels are serendipitous accidents, but this novel, I confess, was plotted out, at least to this point. I’d never started with an idea before – I’d always started with characters – but this time, when I considered writing a new novel, I thought: what would happen if a Darwinian professor was forced to take intelligent design seriously for five minutes? Or twenty minutes? Or a semester? How would he handle his own unease? Would he resort to mockery? Would he have the bravery to take on this sort of project? Would he change his own opinions?

Look, it’s not that I take intelligent design seriously as an academic focus of inquiry, but I do take it seriously as a way for some theists to reconcile what they know about evolution with what they believe about the nature of the universe. It shouldn’t be used in the classroom, yet neither should it be used as shorthand for idiocy. People who come to intelligent design are often seeking some sort of path that leads them to two places at once: evolution and God. Intelligent design won’t get them there, but I don’t blame them for trying to walk down it.

Bill: I also took a philosophy class in college in which the professor–a happier soul than your Andy–demolished all the old-school arguments for the existence of God, including the argument from design, arguing with all of us (a lot of fun, really). Then, at the end of the semester, reviewing it all, he shocked us by saying “But I still believe in God.” Because there were no convincing proofs against it. Was his argument. He said there was no reason God couldn’t proceed in his work through evolutionary mechanics, and that those mechanics might even support a teleological argument. And he left us in the usual philosophy class quandary.

Bill’s Mom: It took you six years to finish college.

Bill: Where did you come from?

Bill’s Mom: Like I’d tell you. Do you ever comb your hair?

Grandma: Sweet cheese blintzes?

Bill (coming up for air): Anyway, Lauren. Your protagonist, Andy, has lost his beloved wife, whom we readers meet through all sorts of memories and all the images, both beautiful and horrible, that he lives with. This makes him vulnerable to Melissa in her quest to save him. I love how you’ve embodied the idea you started with in these two very real-seeming people. Can you talk a little about how the these two characters arose from their opposite corners? I mean without giving away too much…

Lauren: I think the fun in writing fiction (as opposed to living life) is when you get to wind people up and watch them go. What happens if you take a beautiful woman and a frustrated man and lock them together in a room? A lonely child and a bitter grandmother? A starstruck teenager and her sweet, funny dad? Or, in this case, a grief stricken Darwinist and his Creationist student? I put these two characters in a lab together and, almost like I was completing an exercise in dialogue, I had them start hashing out their beliefs. The professor was dismissive. The student was decisive. The professor was curious. The student was animated by a sense of purpose. And as they continued to interact, it seemed to me there were fewer and fewer choices I had to make as an author – because the only things that could have happened are the things that did happen between these particular people.

The trick, of course, is that in order to wind people up and let them go, I have to know them so very well that I know exactly what they’d say and do in all situations, exactly who they are. And so this every time this book became hard to write, I knew I had to dig deeper into the characters and learn more about who they were.

Bill: Where do you work?

Lauren: Depends on the season. I converted my attic to an office, and it’s beautiful up there – reclaimed wood floors, antique windows. The problem is that it’s also totally uninsulated, and therefore boiling in the summer and freezing in the winter. I have a space heater and a fan but when it all gets to be too much I put a cold washcloth (or warm, depending) over my head and retreat to the table in my very air-conditioned and centrally heated kitchen. This is where I eat chocolate chip cookies and answer emails until it’s time to pick up my kid from school.

Bill: Something poets like to talk about: Is computer composition inferior to pencil composition, equal, or superior. For you.

Lauren: Much much much superior. I type with the speed and vigor of a doped up athlete. I write in the unintelligible scrawl of a small child. I can’t read my own writing, in other words, and try never to have to.

Bill: Something composition instructors like to talk about: What’s your process like?

Lauren: 5:00 in the morning.

Bill: Like Dave.

Lauren: It’s the only way. My son wakes up at around 7, and I need those two hours to write in uninterrupted silence, before the news and noise of the day starts breaking my spirit. Nobody emails me at 5 am; nobody asks me for anything. Sometimes I’m able to write after I take my son to school, but often I’m not – I have to go teach, or I have to do errands or take care of the one million things I have to take care of. And at night the only thing I can (barely) do is the crossword. So it’s early morning for me – and often I start to panic when the sun starts to rise, that soon the hard part of my day is going to begin.

Bill: Who are some writers we should be reading?

Lauren: WHY AREN’T YOU READING JANE GARDAM?

Grandma: Please, no shouting! Eat!

Lauren (quietly): Read Old Filth, read The Man in the Wooden Hat, read Last Friends. Also read Double Feature by Owen King, Save Yourself by Kelly Braffet, Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, Another Marvelous Thing by Laurie Colwin, A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra, and if for some reason you have yet to read Lolita stop reading this and go read that.

Bill: Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

Bill’s Mom: Buncha perverts, if you ask me.

Bill: What’s something else you are good at?

Grandma: She is surprisingly good at getting babies to stop crying.

Lauren: It’s true.

Bill: Tell us a secret.

Lauren: Well I won’t bother to state the obvious, that if I tell you it’s not a secret, but okay—one time I was in Portland and forgot to bring enough clean underwear and decided the best choice was to jam myself into my son’s Spiderman undies. I spent the day with an enormous wedgie and still feel a sort of formless shame about the whole thing.

Lauren: Well I won’t bother to state the obvious, that if I tell you it’s not a secret, but okay—one time I was in Portland and forgot to bring enough clean underwear and decided the best choice was to jam myself into my son’s Spiderman undies. I spent the day with an enormous wedgie and still feel a sort of formless shame about the whole thing.

Grandma: I could tell you more.

Bill: Answer a question you would actually really love to answer, in regards to your book or to anything else.

Lauren: This is how I make my famous roast chicken: I buy a kosher bird, not for religious purposes but because kosher birds are presalted so the skin gets crisper. I separate the cloves from an entire head of garlic, rub the garlic over the bird, then stuff the cloves into slits I make in the chicken’s skin. Then I mix up a sort of soupy mixture of smooth (not seeded) Dijon mustard and olive oil and drown the bird in it. I use almost a whole jar of mustard. That’s really the secret. Then I quarter a lemon, squeeze the lemon juice over the bird, and stuff the spent quarters in the cavity. If I’m feeling fancy I toss some sprigs of rosemary over the whole thing. I roast for a little less than two hours at 375, then serve over sturdy greens like escarole with crusty bread for the roasted garlic and red wine for the thirst. And now you know.

Grandma: My roast chicken was different: salt and pepper and paprika. That’s it. Eat, eat. Here you go. Mashed potatoes, too, eat.

Lauren: Roasted, sometimes, too. In the tiny kitchen where my dad slept after he was too old to share the living room with his sister, my aunt. I make the second best roast chicken that has ever been made. It’s clear who made the first.

Grandma: And yet you don’t eat!

Lauren Grodstein’s books include the novels The Explanation for Everything, A Friend of the Family, and Reproduction is the Flaw of Love and the story collection The Best of Animals. Her pseudonymous Girls Dinner Club was a New York Public Library Book for the Teen Age. Her work has been translated into German, Italian, French, Turkish, and other languages, and her essays and stories have been widely anthologized. Lauren teaches creative writing at Rutgers-Camden, where she helps administer the college’s MFA program. She lives with her husband and son in New Jersey.

Bill Roorbach is an unpaid intern at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour.