Table For Two: An Interview with John Lane

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

11 comments

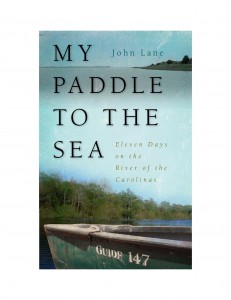

Recently, Dave introduced me to the work of John Lane, a guy who likes to get out on the water as much as we do. John teaches English and environmental studies at Wofford College, in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where he also directs the Goodall Center for Environmental Studies. He is the author of over a dozen books, among them Abandoned Quarry: New and Selected Poems, which was the named the SIBA Book of the Year in Poetry in 2011. His latest nonfiction is My Paddle to the Sea, published last year by the University of Georgia Press, which has just released it in paperback. He’s got a new essay collection, too, Begin with Rock, End with Water, just published by Mercer University Press, too late for this interview.

Bill: Well, John, all my “Table for Two” interviews at Bill and Dave’s start with the same question: where would you like to eat? And what should we order?

John: Conch fritters and Kalik beer in that little bar that hangs over the harbor in Hope Town in the outer Bahamas. There’s a view of the lighthouse and not much has changed there since the Brits left low country SC to settle it in 1780s. They say it’s where Jimmy Buffett got the idea for “Cheeseburger in Paradise.” It’s one of my favorite places and it relaxes me just to think about it.

Bill: We’ll invite Dave, too.

John: He’ll like it. The beer is cold.

Bill: I like it. The view is great, the staff is friendly. They certainly seem to know you—I’ve never seen so many John Lane t-shirts in one place ever. Sailing down from Maine in my Concordia Yawl, yes solo, I really immersed myself in your books, not even looking up for Hurricane Ernesto the other day. My Paddle to the Sea caught my interest particularly, as I’m fond of river stories, river books. I’ll even take a brook, or pretty much a runnel, though I tend to write upstream.

John: All three of us share that love of moving water. Seems I always return to running streams.

Bill: Dave prefers streams of beer, of course. But where is he?

John: He said he was coming. In his new Wal-Mart kayak. All the way from Wilmington.

Bill: Well, screw him, let’s get started. One true story you tell early on is about a trip to Costa Rica, and rafting with your family during flood time on the Reventazón River. The guide dies. It’s natural material, and naturally sensational, but you handle it subtly, make it about family. It’s deeply affecting, also terrifying. I may have focused on it more than most readers, as I’d just gotten back from Costa Rica when I started reading My Paddle to the Sea. But a structural question: Why put that story at the front of a book about the River of the Carolinas?

John: I still have trouble reading it over. What a sad accident. As for how it made it into the book: I was once sitting in a restaurant here in Spartanburg with Barry Lopez and I referred to my work in the 2002 UGA Press collection Waist Deep in Black Water as “essays.” He said, “John, you’re not an essayist; you’re a memoirist.” It got me thinking about the work I do and wondering if Barry was right. Mostly what I write is just various versions of what I remember of my life. Even when I use the present tense, which I do sometimes to spice up the storytelling a little (“We are walking through the shallows of a very large river…”) I’m actually writing about something that happened in the past. My drafts are mostly composed of my sketchy notes and reconstructions through memory. I’ve been good at taking notes all my life, but I don’t tape record my experiences. I’m sure you noticed that this latest book of prose, what they in the business call a “book-length narrative,” is called MY Paddle to the sea. My, my, my, my. So the book actually isn’t about the River of the Carolinas. It’s the story of MY trip down the river. I say all this to get to the question about how the Costa Rica story fits in. From the beginning I saw this tragic week of paddling in late December of 2008 as a prelude to my eleven days on the River of the Carolinas three months later. I couldn’t tell one story without the other. It’s all one story for me. It was just a question of where to put it, where to bring it up. I decided to put I did because in the sequence of events of “my paddle to the sea” we pass that another spot on my home stream, the Lawson’s Fork, where I’d nearly drowned two years later when I was swept under a log. Many ghosts haunt this narrative.

Bill: I thought it was a great beginning, set a tone of danger, gave some real atmosphere, set the stakes. Some people don’t know what a personal essay actually is. I’m not worried about the “my.”

Bill: I thought it was a great beginning, set a tone of danger, gave some real atmosphere, set the stakes. Some people don’t know what a personal essay actually is. I’m not worried about the “my.”

John: But lots of folks who I’ve read to in South Carolina are worried about it. I’ve actually had a few letters from folks who’ve said, “I really liked your book in spite of all that stuff you wrote about yourself. I like the history and all that.” But to me the “my” of the title is very important to me.

Bill: It’s your paddle, bro. And you’re a writer. Historians and scientists don’t always get that. I think Lopez is wrong, by the way, though a writer he is. He’s narrowed the definition of essay to fit what he does, which is more formal, less personal, but no more an essay than the narrative approach or the personal. Our stories are evidence for certain arguments–yours is about nature. And what is an essay but an argument?

John: So much of this book seems to me about other things– like getting old, fear, friendship, nature and human nature… But then I have a bad habit of believing that everything other people tell me about my work is right, and when Barry told me he thought I was a memoirist, then it freed me up for awhile. Thank God, I thought. I don’t have to sit at AWP in any more of those “future of the essay” panels and figure out what a braided essay is after all!

Bill: Memoir is one of the great arts, storytelling one of the greatest modes of human communication. I was glad to see your interest in the Rivers of America series, all those great authors and popular authors sent out to write about the great drainages. Some were pretty good, and the series, sixty some books all in all, was wildly popular. Could we even conceive of such a series today? What would it look like? Would our books fit in?

John: The idea of the river book has changed so much. I can’t imagine a river book being wildly popular today. I think ours would not have fit in back then. Too much use of the “I” for that time. I think we’ve inadvertently started our own series. To tell the truth, I actually conceived of my book because I was so disappointed with Henry Savage’s River of the Carolinas: The Santee. I admire Savage but I read his narrative and thought, “Well, I sure do know a bunch of human history now, but where’s the damn river?” I wanted to know what it felt like to paddle the Santee and he never actually does that. He’s always flying at about 5,000 ft. I feel that way with many of the books in the series. But that was before the day of the personal narrative.

Bill: Before the day of the personal narrative? I think Thoreau was all about personal narrative. Also rivers. As in The Concord and the Merrimack.

Bill: Before the day of the personal narrative? I think Thoreau was all about personal narrative. Also rivers. As in The Concord and the Merrimack.

John: OK, before the day when the personal voice of the first person nonfiction narrative was the ruling genre of nonfiction, as it seems to be today. That sort of objective “expert’s” voice that Henry Savage chose to write from was more common in popular nonfiction books of his time. And to tell you the truth, I think Henry D’s A Week on the Concord & Merrimack coulda used alot more personal voice in it as well. I seem to remember very, very long digressions in that book that leave the river far behind. It’s deadly to try and teach that book. I’ve tried it two or three times.

Bill: Just the book Savage wasn’t writing.

John: My first draft was called River Letters to a Dead Writer. I wrote a series of letters to Henry Savage as I floated downstream telling him what he had missed by not canoeing the length of the Santee. In some ways I still wish I had written that book. I wanted each letter to start with an actual GPS coordinate of some spot where I was writing from on the real river.

Bill: What happened to that idea?

John: I kept the journal on the trip, using this writing machine I bought called an Alphasmart, a lightweight green moulded plastic keyboard with a memory card to hold about 60 single spaced pages, maybe 20 of my “letters.” It runs on AA batteries. I typed on that thing every night at camp for a solid hour, sort of a modulated modern Kerouac with his teletype roll. When I returned I told my wife about the idea of the River Letters and she said, “I don’t think this is a good idea if you want people to read about his trip. It’s way too literary.” So I used the 20 letters as my first draft. There are paragraphs that didn’t chance much still there.

Bill: Where are those conch fritters? We’re not waiting for Dave, are we?

John: The conch fritters are on the way. In the islands you’ve got to settle into their time, even if you’re hungry!

Bill: How has it been publishing with Georgia? They do such a good job, and have loyally published your books as they come. What brought you there in the first place?

John: What brought me to Georgia was that they wanted my work, they treated it well, and they keep it in print. Barbara Rass was my first editor and she’s a genius and believed in a big thick environmental list. When she left, Georgia continued in that tradition. New York has never wanted anything that I have written, though I have tried. I’m a university press kind of guy. Georgia has been great to me. I’ve done five books with them now, an anthology I co-edited with a colleague on Southern Nature Writing, a book of “personal narratives,” and three book-length narratives. All have sold out their hardcover editions and been published in paperback by Georgia, which means they sold about 1000-1500 copies. That doesn’t mean much on the literary radar, but it’s been gratifying for me.

Bill: And certainly to Georgia! We should talk about your teaching, especially any ways it intersects rivers and nature.

John: I came to teaching by an odd path and that path continues. Wofford’s a good school. I went there and was the campus poet with no ambition to do anything but be a wandering bard. I graduated, ended up in the late 70s/early 80s dropping out of a few good graduate programs (Breadloaf, UVA, Arkansas) and then ended back at Wofford teaching freshman classes in ’88. The college hired me year to year for almost a decade with only a B.A. degree. I’m a lucky man. How many folks get to teach college with a B.A.? I kept writing, heading out west every summer. Then I went back and finished my MFA in poetry in first low rez class at Bennington. From ’96 to present I’ve been a more traditional college prof with tenure, committees, and investment in all things academic. I’ve been a program builder, as I was always unhappy with the system as it was. So I worked with a colleague to build a concentration in creative writing (I taught poetry and the personal essay), then with another colleague I created a 3-year program (highly funded by a big grant) called “Cornbread to Sushi” where we taught seminars on the changing South through the eyes of its living and dead writers and toured and visited and ate meals with writers in January with the students. I also got involved for 10 years team teaching a freshman class (we called it a “learning community”) with a biologist. It was a class we called “The Nature & Culture of Water.” Every Thursday we’d take them on day-long excursions– we paddled rivers, visited sewer plants, did water quality work, talked with priests about Baptism. Out of this grew the idea for an environmental studies program, which I developed three years ago, and now has three faculty and 49 majors and minors. I teach the humanities and writing part of the core. Recently we got another huge grant and we’ve designed a 3-year project called “Thinking like a River” which I’m deeply involved with. We’ll work to get every one of our students to take part what we are calling floating seminars. So my teaching “career” has been very dynamic. Way, as Frost said, leads on to way.

John: I came to teaching by an odd path and that path continues. Wofford’s a good school. I went there and was the campus poet with no ambition to do anything but be a wandering bard. I graduated, ended up in the late 70s/early 80s dropping out of a few good graduate programs (Breadloaf, UVA, Arkansas) and then ended back at Wofford teaching freshman classes in ’88. The college hired me year to year for almost a decade with only a B.A. degree. I’m a lucky man. How many folks get to teach college with a B.A.? I kept writing, heading out west every summer. Then I went back and finished my MFA in poetry in first low rez class at Bennington. From ’96 to present I’ve been a more traditional college prof with tenure, committees, and investment in all things academic. I’ve been a program builder, as I was always unhappy with the system as it was. So I worked with a colleague to build a concentration in creative writing (I taught poetry and the personal essay), then with another colleague I created a 3-year program (highly funded by a big grant) called “Cornbread to Sushi” where we taught seminars on the changing South through the eyes of its living and dead writers and toured and visited and ate meals with writers in January with the students. I also got involved for 10 years team teaching a freshman class (we called it a “learning community”) with a biologist. It was a class we called “The Nature & Culture of Water.” Every Thursday we’d take them on day-long excursions– we paddled rivers, visited sewer plants, did water quality work, talked with priests about Baptism. Out of this grew the idea for an environmental studies program, which I developed three years ago, and now has three faculty and 49 majors and minors. I teach the humanities and writing part of the core. Recently we got another huge grant and we’ve designed a 3-year project called “Thinking like a River” which I’m deeply involved with. We’ll work to get every one of our students to take part what we are calling floating seminars. So my teaching “career” has been very dynamic. Way, as Frost said, leads on to way.

Bill: Do you have kids?

John: Betsy had two boys when we got together, and so I have a great family. Both are in their mid-20s now.

Bill: Wasn’t Betsy in a class of mine up in Vermont?

John: Yes, she took your class back in 1996. She says you are a great teacher. She’s a very good writer and the director of the Hub City Writers Project here in Spartanburg, and now mostly a writer of grants.

Bill: How do you find time to parent and teach and write?

John: I’ve always been very disciplined with my time. I have always taught mostly afternoon clsses and I divide my time between writing and teaching. I do my writing work first, in the mornings, rising early (like now, it’s 8:15 and I’ve been up working since 5:30) and then I go to school at lunch time and disappear into that world. The parenting has mostly been Betsy, though the boys tell me that I’ve influenced them in many ways, especially in my willingness to take unconventional paths. One son is a gifted musician who took a leave from college, toured successfully nationally with his own band for almost five years (now he’s back in school at Fordham in New York City), and the other son graduated from Tulane with a political science degree and teaches sailing and does sailboat charters on the Hudson River for Atlantic Yachting. They are both excellent kayakers. We’re headed off on Monday on a family sailboat adventure in the Virgin Islands.

Waiter: Conch Fritters.

John: Ah, here they are now! Dig in! Golden brown orbs from the sea! The pounded flesh of armored bottom feeders!

John: Ah, here they are now! Dig in! Golden brown orbs from the sea! The pounded flesh of armored bottom feeders!

Waiter: There’s a man in a kayak down there.

Bill: It’s Dave!

John: Dave!

Bill: David!

Waiter: He’s only paddling faster!

John: Sometimes he hates this kind of literary talk.

Bill: No, that’s a submarine coming up next to him!

John: There’s a hatch door opening! They’re dispatching a zodiac to catch him!

Bill: He’s been eaten! Kidnapped!

John: I get his fritters!

[We eat. The conch is, indeed, delicious. John and Bill divide Dave’s portion.]

Bill: Poor Dave.

John: Those BP submarines are so stealthy!

[We eat, we drink, we ponder.]

Bill: Dave would want us to continue.

John: I will drink his beer.

[More eating, more pondering.]

Bill: What are some of the great river books?

John: My basic list starts with Concord & Merrimack (though I still think Thoreau digresses too much), runs through Huck Finn, Powell’s canyon book, Heart of Darkness, Hemingway’s river short stories, “Big Two Hearted River.” And lots more: Deliverance, A River Runs Through it, Death of a River Guide, The River Why, Lopez’s River Notes, Frank Burroughs’ The River Home, Ann Zwinger’s Run, River Run, and on and on. Of course there is your Temple Stream, which I love.

Bill: I believe I’m the only woman on that list.

John: Pretty male heavy, I know. Janisse Ray starts out her recent river book Drifting into Darien (about the Altamaha in Georgia) saying, ‘I know this river story has already been written. Over and over it has been told… but those who were not transported by water will never know what really happened.’ I like that, the idea of being “transported” (literally and figuratively) by water. Why are men transported more than women? Have we just had more opportunity?

Bill: Maybe women are just better at keeping it to themselves.

John: I once had a colleague at Wofford who said, “The only reason you go out and do all those crazy things is so you can come back and write about them.” I guess he was right.

Bill: You’ve talked about Goodbye to a River. Is all nature and environmental writing elegy these days?

John: No, not all. I think of Lopez’s River Notes. That doesn’t strike me as elegy. And I wouldn’t call My Paddle to the Sea elegiac. At least it’s not an elegy to the river. I celebrate the experience of floating and thinking and the river’s in no danger. It’s been degraded and dammed (damned?) and dirtied but it’s still running. I don’t think David’s book about the Charles is elegy. I wish he could be here to comment on this.

Bill: I’m afraid they’ve already got him in the BP undersea laboratories for a mind scrub. He should never have crossed those fuckers.

John: Dave’s Tarball book is one powerful piece of nature writing. In it he brings together all the best we can do. It’s got spot-on description of the natural world, great characters, humor, and an important story. No wonder they sent that submarine to capture him. Didn’t you love the way those osprey rallied to his defense to dive bomb the approaching zodiac as it was chasing his kayak down? It’s like a James Bond movie crossed with Wild Kingdom!

Bill: But alas, no osprey is a match for BP.

[We eat, we drink. We check our cell phones. Have a long look at the latest post on Bill and Dave’s, which appears to extol BP! Photos of Dave shaking hands with its new CEO! We eat, we drink. Bill casts about for questions, his heart heavy.]

Bill: You’ve been visible online a long time. Tell us about the Kudzu Telegraph.

John: The whole Kudzu Telegraph thing started when I became an activist around the issue of the development of a local girl scout camp. First I wrote an essay called “Something Rare as a Dwarf-flowered Heartleaf,” about sneaking into the camp with a botanist and looking for a federally endangered wildflower, and I made a pamphlet and mailed it out as an appeal to the 100 most powerful folks in Spartanburg, urging them to stop the sale of the camp, a sort of Tom Paine appeal to the community. Then I revised the piece and it appeared in Orion Afield and was a close runner-up for the SELC Philip Reed Prize for Southern Environmental Writing.

Bill: Which Dave later won for Tarball Chronicles.

John: Yes, Poor Dave.

Bill: He should never have crossed them.

John: I published the Orion Afield version in my book Waist Deep in Black Water. Then soon after, about 1997, I created a environmental e-newsletter called the Kudzu Telegraph (the name came from corrupting Jimmy Buffett’s “coconut telegraph”) alerting folks to local issues. It was very popular, a sort of early blog, distributed via an email list every week. I think the blog lasted about 6 months until I started tangling with local politicians (one guy I knew pretty well called me on the phone when one issue came out and screamed at me, “you used to be a poet and now you’re a damn journalist!”) and I became uncomfortable with how much time and energy it was taking being the local “watchdog.” Then beginning in 2005 I revived the idea in a print column for five years, a local column for a local paper, mostly about local environmental and outdoor recreational subjects. It went out to about 80,000 readers in Spartanburg, Greenville, and Anderson. I liked the idea of the short form—my editor gave me about 600 words per week. It felt almost like writing a sonnet. People loved it. I’d get stopped on the street all the time by strangers (my picture appeared at the top of the page in a hat) and I ranged far and wide with the columns. I never missed a Monday deadline in five years.

Bill: How did working that way inform your thinking and writing?

John: When I was in graduate school the final time (after dropping out of three programs as a youngster, when I finally finished an MFA in poetry at Bennington’s first low-residency class in 1996) my mentor Liam Rector called my view “hyper-local,” and it was hard for him because he believed very very deeply in a “national” or even “international” (ala old Ezra Pound) literary culture and worked until his death to create one through AWP and through the Bennington program. This interested me, but didn’t compel me. I was deeply interested more in how one can practice and live a high quality local literary life, one that imagined one’s audience as local first. I saw this as the winning hand I’d been dealt. I teach at the Southern college I graduated from in the South Carolina town I grew up in and for over a decade I could stand at my office window and look out and see the smokestack from the mill where my great grandparents had met and married. I was rooted. By this time I’d also begun to work with Betsy, the woman who would become my wife on the Hub City Writers Project on a local press and literary organization. Our first book, which I co-edited with her, came out in ’97. (Note: John wrote about all this in great detail in a piece that just came out in an anthology from UGA called The Bioregional Imagination, and the piece is up online on Southern Spaces. Since that time Hub City has published over 50 books, many of them about local history and such.

Bill: Great place to visit, thanks.

John: So this e-newsletter and column grew out of these deepening feelings about the local. Spartanburg was growing in that late 20th century ugly suburban way. I didn’t like it, so I fought sprawl in my own way. I went toe to toe with the developers sometimes. Other times I just wrote about animals or river trips I’d taken or local natural history. Each week I toiled to write a good piece but I imagined my audience as my neighbors, not some abstract literary audience spread over the whole country. Now you’ve got to remember I’d been publishing prose for a decade by this time and poetry for twenty years and spreading both through the literary quarterlies and journals. I had been fairly successful in that national scene, and I was deeply embedded in a eco-writing scene that revolves around the group called ASLE (the association for the study of literature and environment), but I wanted something else. I wanted to explore the near-by for the near-by. I never gave up writing the pieces I’d send out to more national markets, but I put a great deal of thought into keeping this local conversation going with my neighbors. (One old conservative high school friend once told me, “John, I love to read your column each week. It lets me keep up with what the Communists are thinking.”) In an odd way this led to my book Circling Home, a book where I place a cracked saucer on a topo map with our house at the middle and explore for a year the “layered” history, human and natural of this place, a book a great deal like your Temple Stream, or something I would imagine Dave will write about that little shack he has on the marsh in Wilmington, or Walden, or that great book by John Hanson Mitchell, Ceremonial Time or another book I love, Wyoming’s Mary Back’s Seven Half Miles from Home.

Bill: Or how about William Least Heat Moon’s Prairy Erth? Or just about anything by Terry Tempest Williams?

John: Yes, and a dozen other books that have been produced all over the country. I never abandoned my eye for the other scenes. After all it was Ezra Pound who said, “Intelligence is international, stupidity is national, and art is local.”

Bill: Ezra Pound was crazy.

John: Yes, he was crazy, but he also knew things, deep things, crazy-like-a-fox things.

Bill: Too anti-Semitic for me.

[The waiter comes with the tenth order of conch fritters, and cold beer. Much pondering and eating and drinking ensues. High thunderheads mass at the horizon, gorgeous.]

Bill: Here’s a question I ask everyone: Tell us about your career?

John: Where and how to start? I’ve published poetry for 35 years, including many collections from small presses and a New & Selected Poems, Abandoned Quarry, out last spring from Mercer University Press. I’ve had a play published and produced at several colleges called “The Pheasant Cage,” and co-written a country song that have appeared on Hollywood sitcom (“Split-level Woman,” sung by Baker Maultsby & Peter Cooper. My co-writing cut on the royalities? $100), and written unproduced movie scripts and toiled at unpublished novels, and I’ve thrown myself at nonfiction prose now in four collections of shorter pieces (Weed Time, Waist Deep in Black Water, The Best of the Kudzu Telegraph, and out this fall from Mercer, Begin with Rock, End with Water) and three book-length narratives (Chattooga, Circling Home, and My Paddle to the Sea). I’ve also edited five collections of personal essays by other folks. So I’ve been at prose for twenty-five years now. I’ve taught now at Wofford for closing in on 30 years. At Wofford I’ve moved from teaching creative writing to teaching the “environmental writing and humanities” classes in a quickly expanding environmental studies program. I’ve written and written and written. I worry sometime it’s too much. I always remember that great quote from Ford Maddox Ford about how he wished he’d written many less words and planted many more kitchen gardens.

Bill: And eaten more conch fritters. I keep thinking of those “river letters” you mentioned, the ones you wrote to Henry Savage. Let’s have the waiter read one to us.

Waiter [mellifluous tones]:

RIVER LETTERS TO A DEAD WRITER

For Henry Savage, Jr. (1903-1990)

Letter I

Dear Henry: We’re now about four miles below Pacolet, South Carolina, on your Santee River. I say “your” river because as a literary property, I’ve decided you own the Santee. It’s your literary ghost I’m chasing on this trip. Writers are always chasing ghosts, and often they are dead men or women who achieved something great or compelling or shocking in their lifetimes. Sometimes it’s a writer’s craft that makes them a quarry worth chasing, but sometimes it’s simply the subject matter they choose. In this case what associates us and makes us kin is this river I’m on. It’s called the Pacolet here in the upcountry of South Carolina, but it will be called the Santee by the time I get to the sea in eleven days.

I’ve got your Santee: River of the Carolinas in my sights with every paddle stroke on this personal journey to the sea. You published your book in 1957, the 51st title in the now legendary Rivers of America Series. With its publication you took your place among other chroniclers of the noteworthy river systems of America. That book, your second, sold well, though it didn’t exactly make you, Henry Savage, into a household name. I had to find my copy on the used book market, and I probably paid too much for it because I wanted your signature so that I could ponder your handwriting and wonder what it said about you, the man.

Buying that fifty-year-old book began this conversation between us. I read it in one gulp. Though I admired much about it, the book left me with too many questions about the river. This was good in a way because if writers are always chasing ghosts they are also looking for ways to put ghosts to rest.

What I was looking for in reading your book was not information about the Santee. I was searching for an opening, a place where I as a writer could add something of my own to the river’s literary life. Every place has its story, Henry, and after reading your book I knew that I wasn’t about to tell yours. I have my own voice and I want it to be heard along-side yours.

After a few pages I’d judged your book lacking in what I want today from a river book. I want to sense the writer’s been there—I want to smell, taste, see, and hear the river and feel as if the writer has dipped a paddle in as many miles of it as possible. I want the river to have a body all its own and a presence that somehow pervades space beyond the cover and pages. I think what I’m looking for always in a river book is what your daughter Hope Savage left home to find back in the early 1960s—pure experience. I’m after the same sensations she sought in New York and India. It’s just that I’m out to find them close to home.

I imagine Hope probably disappointed you since she took up with the Beat poets and wandered through India with them, but since discovering her about the time I discovered you I’ve thought her life heroic and interesting through the little fragments that I know. She, like you, lives now on the edges of literary history, and I’ll admit that’s where I’d like to end up years from now too. I’ve got time I think to improve my literary lot. You do not. Time left you marooned in a thousand used bookstores and private collections. Your seven books are all out of print, and your archives are kept off-site at the Caroliniana Library in Columbia, SC. I’m sure you are affectionately remembered by kin, and there are a few who pick your books up—like me—and attempt to reconstruct your sensibilities. With you it’s a little like Auden said of Yeats in 1939, “he became his admirers.”

Well, I’m one of your admirers. In time I hope this work of mine on the Santee will take its place on some shelf next to your book.

Time’s a funny thing, Henry.

And river time is even funnier. When you are in a boat paddling along the world slows to the pace you set. It’s nothing like being in a car. Take today, my first on an 11-day river trip from my backyard, high up in the Santee system, to the South Carolina coast. I sat with the river drifting onward. How long has it been since this flow has ceased? Dams haven’t stopped it. (And didn’t I sense from your book that you too are no fan of damming rivers?) Dams impound a little of the flow in a conspicuous puddle but they don’t really stop anything. Every time the river rises the flow continues. Flow never stops, Henry. Flow just keeps on going.

Our river has been at it for 160 million years, since Africa and North America pulled apart and what we now called the Atlantic Basin opened up. You’d find all that the geologist have to say about river formation interesting Henry, but continental drift and plate tectonics was before your time. I’ll give you this. You did have a knack for natural history in your time, though the editors of your book made you cut out so much of it out. They didn’t think that’s what would sell.

It’s now over 50 years after your book’s publication and 20 years after your death down in Camden. So here’s a question I’ve been wanting ask you for years: Did you ever spend a day canoeing on the Santee when you were writing your book? I couldn’t imagine writing it any other way than this. You see, for me the river is not a score by which I sing human history, as it seems to have been for you. I’m interested in what humans have done on or close-by the river’s course, but I’m more interested in trying to show the river itself.

Don’t get me wrong, Henry. I’m no scientist, so I’m not going to tell you about my research in hydrology or warblers breeding in the riparian zones, or coyote use of river corridors. I’m a poet like your daughter Hope was, and you might find some of my flights of fancy on this trip hard to digest. I guess for me every journey on a river is like Hope’s travels in India. They take me away. They show me that the world is bigger than we are, even we as a species. They let me travel back in time and believe (feel?) for a day or a week that the modern age was held at bay. One of my friends, a religion professor, says that’s the myth I live by, that Eden myth, that belief that there was some moment deep in the past when things were more perfect than now. There’s something about being on a free-flowing river that makes me believe even deeper that there is a better way than modernity.

But back to the river, Henry. As I said before, up here this branch of the Santee is called the Pacolet. I think you mention it maybe three or four times in your book. Did you ever see that old New Yorker cartoon where New York City is the center of the universe and everything loses resolution as the eye wanders farther from Manhattan? As someone bred in the upcountry I feel a little like that when I read your “history” of my river system. The way you tell this story we in the upcountry are bit players in a play that unfolds century after century at the coast. Not much happened above Columbia. But more about that later.

So what did it feel like to be on the Lawson’s Fork and then Pacolet Rivers for nine hours today? Rainy, Henry. We had showers off and on all day. It wasn’t the weather that I ordered up for my paddle to the sea. I wanted sunshine and mild temperatures, but instead we got rain and it might continue for days. So it’s chilly and wet and all day there were low clouds and showers.

Five of us paddled down today from my backyard on the east side of Spartanburg. There was my Alaska friend Venable Vermont. There were my video making friends Chris Cogan and Tom Byers, who wanted to shoot the first few days of paddle to the sea and meet us at the coast to document it when we reach the ocean. I’d also had enlisted a friend, Louie Phillips, to sort of act as “best boy” on the video shoot. His main job was ensuring that Chris got downstream with his expensive equipment dry.

We left from behind our house at 9:15. A friend of mine, Ron Robinson, came to bless the canoe and gave a great prayer. He even read something he’d found I wrote about the very river we started on: “A ruined river road forms our southern property line, /risks flood when the Lawson’s Fork rises. /Yesterday walking down slope, I slipped off my shoes and waded/the orphan current, glimpsed upstream/ a flowing, a future, and the run-off moving through.”

Henry, when you’ve written as much as we have, sometimes something sounds foreign and distant. Well, that’s how those lines sounded to me. But I listened really close and they became like a mantra I kept tucked away for later in the trip when I might need them.

Ron’s my college chaplain at Wofford College but he’s also a mountain boy, part Cherokee, so I took seriously what he offered in a way my lapsed Methodist spirit would find odd.

After Ron’s prayer we launched and we made our way down from the house. Just downstream we stopped for a few minutes at a huge pile of trash caught behind a down tree. V and I talked about how terrible it is that people do this—throw all their trash in the river. Maybe that’s what you were getting at Henry. Maybe we up here in the upcountry have never gotten beyond those old habits. In that trash flow there were bottles, balls, kid’s toys, etc. That trash stop was something. A few minutes later we had a good run of a 19th century industrial cut in the bedrock a half-mile below our house. Wee call it “the shoot.” Then there was the portage at Glendale ended up being pretty easy. V carried our canoe on his shoulders all the way to the put-in near Steve’s house. He looked like one of those animals the Greeks believe in—half man and half canoe. Everybody put back in below Glendale and we headed down what we call the “Hall of Waves.” Fun one. The level was good. Everybody was impressed with the yellow oil tank in a little rapid a mile downstream. A little further along, “Little Five Falls” was a little difficult. Not so much water there, so we didn’t really run any of the drops. Too shallow.

Lots of great birds today: blue herons, lots of kingfishers, an osprey, a bard (sp.) owl in a tree near Glendale, red tail hawks, warblers in the flood plain. What did we talk about? We talked mostly about the difference between up country and low country; told paddling stories, and wondered whether we would make it to camp tonight in time to cook dinner before dark.

It was quite beautiful as river days go. If you had ever seen this river system from the cane seat of a canoe like I did today you would have liked it—the mountain laurel bluffs, the dark banded gneiss in the riverbed, wild cherries blossoming in the woods. I know enough about you to know that’s true.

I thought about you many times as we paddled because I want to see this river from my end, my upcountry end, rather than see it the way you did in your book—from the coast, as if all history, even mine, started down there. I guess some of my history did start there—the rich people’s history—but I’m not very interested in rich people’s history. I want people to know this river in a different way, from a different point of view—from here a few dozen miles from the headwaters all the way to the sea.

So Henry, tonight our camp will be high and dry, three miles on down the Pacolet. Tomorrow is a day without a portage, and we’ll sleep tomorrow night on Goat Island, about a mile after the Pacolet’s confluence with the Broad. It’s time to stop writing for now. Good night Henry. I’ll talk to you tomorrow.

Bill: Love it.

Waiter: Your friend is coming up the hill.

[Sure enough, full stride, here comes Dave, dripping wet, huge grin on his face, glowing like sunshine, with an osprey perched on each shoulder.]

John: Just quickly, then: Never thought about it until now but Henry Savage was a typical old-time Southern intellectual, who masked the life of the mind with something else– doctor, lawyer, planter, exile, idiot. As Tara Powell puts it in her wonderful recent study The Intellectual in 20th Century Southern Literature, “The South has never been noted for its deference to the intellectual.” Powell even calls these intellectuals “beleaguered.” In Savage’s case he was a lawyer and came to writing natural history books later. His idea to write the Santee river book was a blind submission to the Rivers of America series and the editorial letters in the archive in Columbia show it was quite a struggle to get them to accept it, and with the form of it, and finally with how much natural history to include. Henry wanted more nature and the editors wanted less. So he had to struggle with being a writer and with the demands of the publishing (and intellectual?) capital of the time, New York. There’s even one moment when the sales department of Rhinehart & Company suggests that there can’t be more than a couple hundred readers in the whole Santee watershed to buy Savage’s book!

Dave: Gentlemen, hello. I bring urgent tidings. I have wronged a great and benevolent company called BP. This must be made right. [He pours us brimming glasses of Corexit oil dispersant. We toast and drink.]

John: Arghh. [Falls to floor, kicks a few times, is still]

Bill: Got him.

Waiters: [removing their John Lane t-shirts to reveal BP logos on biceps, Dave logos on chests] All hail!

Dave: Aw.

Enjoyed this. My favorite part, though their were lots of good ones, that an entire department grew from the brilliant creation of a “nature and culture of water” class. I believe if one environmental science class were required curriculum in every undergraduate education, just as you would have a required reading list for a lit. class – there’d be a greater understanding of our own impact on the world, and some understanding, or at least awareness, of the sustainability Dave struggle with in his travels.

As David Suzuki says, we don’t even know where our drinking water comes from, where the electricity comes from, and at what cost. Or where the garbage goes.

Cartoon Dave learned, on his submarine adventures, the folks at BP are good guys and gals, just providing a service. A service WE demand at great peril to the workers who provide it and the environment (and there’s a word that’s been beaten to death with over-use) which is exploited for it.

Great body of work. John, but this bit about being trapped under a submerged log while out recreating, scares the crap out of me! The power of water!

Well, I didn’t get trapped on purpose. I understand the power of water better than most (canoes and kayaks on moving water for 30 years) but as the full story illustrates (to be found, as Rick points out, in CIRCLING HOME) That lapses in judgment happen and when they do it’s possible you’ll pay a big price. Those moments on water always go a long way toward showing me that the wild world isn’t a Six Flags ride!

Do you know there’s a whole philosophy of water department at the University of North Texas?

My favorite title of a book of poetry: THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF RIVERS by Jim Harrison.

I really appreciated John’s comment: “I imagined my audience as my neighbors, not some abstract literary audience spread over the whole country.” It seems the slogan of the past few years (especially) is to [fill in the blank]”local”–especially in terms of food and the restaurant scene–and I like how this idea applies to writing, too.

Local– it’s something I got onto early. I really talk about literature and localness in a great deal more detail in the piece SOUTHERN SPACES republished from The Bioregional Imagination anthology. The link’s in the interview.

I’ll definitely check out the link, John. “Local” is definitely something I’ve been getting into only more recently. I find it helps me summon my cnf “voice” slash “I” when I think of writing for a local audience…

Hey Rick! That piece about the Charlotte whitewater park is in BEGIN WITH WATER, END WITH ROCK, along with about 12 more river narratives. (It’s a watery book!) Hope you’ve had a chance to get on the water this summer.

Love the infinitely dynamic and changing force of water too—always makes me feel humbled. It seems that the most memorable experiences (and stories) are when we end up in the drink. The near disasters are what get the heart pumping, and John captured one on the Lawson’s Fork well in Coming Home. Looking forward to reading the latest book and essay collection. I flipped at the Whitewater Center after wrongfully assuming it would be something like a water slide. John was there to help pick up the pieces, and later sent me a good essay (with an argument, but some memoir too) on this “recreational Oz.” Hope it and others like it are in there . . .

Circling Home (I meant)

Love your books, Rick, A Natural Sense of Wonder, about bringing kids into nature, is terrific.