Reading Under the Influence: A Look Back at Antonya Nelson’s Expendables

categories: Cocktail Hour / Reading Under the Influence

1 comment

.

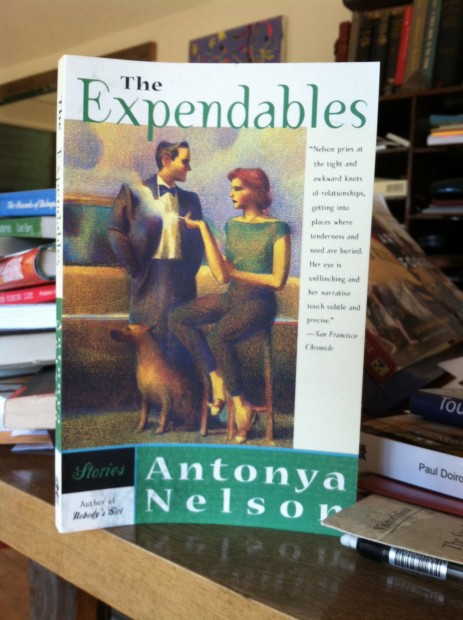

Some years ago, in 2000, to be precise, I won a Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. I rented a fancy tux and headed Milledgeville and a grand award ceremony. But the real prize was seeing my collection, Big Bend, beautifully published. This yaer marks the 30th anniversary of the prize, and the editors asked us winners if we’d write brief posts about one another’s books for their blog. They are also offering a pair of e-anthologies of work from all the winners, coming soon. And before long, an e-book of Big Bend will finally be available, hoorah! Below, I’ll offer my post for the “30 Days of the Flannery O’Connor award,” this one about Antonya Nelson’s winning collection from 1990, The Expendables.

Possibly the best way to discuss Antonya Nelson’s stories would be to quote from one. Even better would be to reproduce a whole story, maybe the whole book of stories: then you’d know more than I can ever tell you. Like the woman (who is a friend, this post a toast), they’re funny, they’re deep, they’re weird at times, with powerful narrators who aren’t quite sure what to make of things, and huge casts of characters swirling around them like dust devils, and all the stuff of life: pets, food, dirt, love, disaffection, appointments, family, friends.

But I’ll just quote a paragraph from the title story (whose narrator is male, not something the reader needs much to think about, as Nelson makes it clear immediately and keeps it clear: this guy’s no girl in disguise):

Yvonne’s roommates pulled up and I cringed along with my mother, though we’d both seen their car plenty of times. They’d hand painted an old Falcon purple and gold. Over the hood was an enormous silver cross. Other identifiable shapes dotted a landscape of gold clouds and purple hills. A rainbow broke in half when the passenger door opened. Neither of my sister’s roommates had a driver’s license or insurance, and whenever they parked they always left the key in the ignition. They’d once told me they believed responsibility had to come from within.

This comes in the early middle of the story, but it could easily be the first paragraph of a great story or the last. It carries within it the whole story as any great paragraph should, and all the genius of Nelson (did I say she’s a friend? Clink!). There’s the management of a large cast, the disruption of order, the central object, in this case a Ford Falcon, which was the budget Ford of its day. Its paint job tells us who these people are with clarity and precision and economy. That a rainbow breaks in half, well, that tells us about the dreams of youth, impossible to begin with, no better now that the paint has been spread, breakable and unreal. The whole crew (along with the story) is clearly headed for trouble, or at least life. The narrator decides he could easily live with these young women, all but one.

Down the street from the wedding of the sister of the narrator a funeral is going on in the home of folks who might be gypsies, anyway, that’s what the narrator’s family calls them. The sexy jerk his sister is marrying arrives with his cohort just as the funeral procession comes down the street toward the church at the other end, also just as the narrator is attempting to park the Falcon, his job for the day. And the groomsmen don’t bow their heads in respect, far from it—instead they shout and taunt the so-called Gypsies. “No more dying today!”

Wow. The big people, here, the gypsies, ignore them utterly, carry on. Later our narrator smuggles a huge fruit basket off the gift pile and down the block and offers it up in apology. That’s enough: this guy, we love him. Why? Because he’s good, he’s kind, he’s transcended his destiny.

Meanwhile, the new brother-in-law gets shot in the face, whether by friends or enemies it’s unclear, hit or hazing, doesn’t matter.

You can tell a great story when it’s impossible to read on. You need a day to think. Then on to the next story and then the next, never in order, often more than once, in this case readings two decades apart. But let me tell you: This is a collection that holds up. And Tony is better than ever.

Dear Bill… Congrats! I didn’t know that.

LB