Not Forgotten, But Gone

categories: Cocktail Hour

Comments Off on Not Forgotten, But Gone

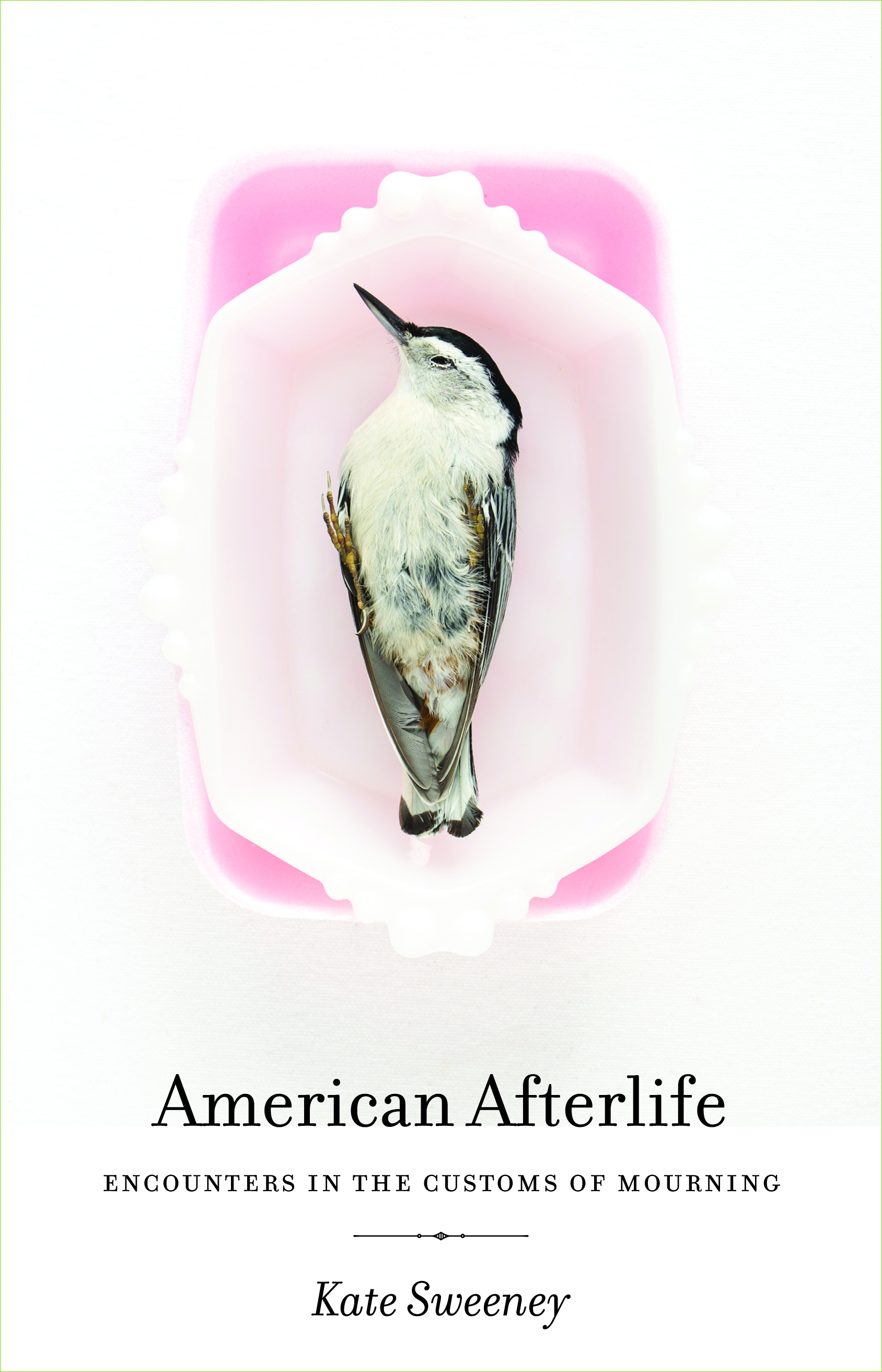

My former student (and current friend), Kate Sweeney, has a new book out: American Afterlife. Here’s an essay about writing the book:

There’s this chestnut that I learned as a college student studying anthropology about “making the strange familiar and the familiar strange.” (I’ve since learned it’s commonly attributed to the Romantic poet Novalis, but I still like to think of it as an anthropological thing.) This phrase characterizes a great deal of my favorite writing: A seemingly foreign subject is found to contain some kernel that rings true in a startlingly personal way. Or more jarring: something you thought you knew is revealed in some curious new light—shifted, now, into something that can never seem quite comfortable again. Making the strange familiar and the familiar strange has a lot to do with my answer when people ask, “Why did you write a book about death?”

Early on, my answer to that question would be this half-truth (more incomplete truth than half-lie): I’m kind of a research geek. And if there’s any subject out there that’s rich in little-known facts you’ve got to do a little digging to uncover, it’s the American funeral trade. Writing this book, I learned all about how coffins became caskets, how home funerals became funeral homes, why burial vaults were invented (grave-robbers!) and why on earth we still have them today (the pursuit of golf-course smooth cemetery grounds and, to some degree, body preservation).

But it was investigating what I imagined would be one of the strangest phenomena of all that brought me thundering back to the shock of the familiar.

Memorial photography. You know: those photos of family dead that were especially popular in the second half of the 19th century (and which remained popular in rural areas and parts of the South into the 20th). I relished this investigation; I even looked forward to shocking my friends with morbid facts. After all, it’s easier to view something as odd when it’s removed from you by years and years. And it’s easier still when all of American society agrees with you: Memorial photos are creepy. Odd. I didn’t even pretend to understand. Why would anyone want photographs of their dead?

Kate!

Then I met Oana Hogrefe, and things started to change. Oana volunteered for an organization called “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep,” for which she took “remembrance photos” of dying or deceased infants. A hospital chaplain would call Oana, telling her that a baby had hours to live, or that they were planning to unhook whatever apparatus was keeping it alive; could she be there? And she would go.

I talked with her on the phone and I understood these basic facts, but I still didn’t understand why. We set up our first interview. Then I began researching the history of memorial photography, and the “strange” started to shift.

In the 1800s, people saw a lot more death. Death by TB, flu and childbirth were all common. In those days, the Grim Reaper showed up fairly often at home. And this was what people preferred. Think of this way: You knew you were going to die. All your life you’d experienced deaths of siblings, friends, and maybe even a parent. You just hoped that when it happened to you, you would be in your own bed. This hope evolved into an ideal known as the “good death”—death at home, surrounded by loved ones, and ideally, saved. (The whole thing stemmed from Evangelical Christianity and the Second Great Awakening, but pervaded American culture. Even people who weren’t Christian hoped for death at home with family.)

The good death found its way into books, plays, and later even movies. The tradition that began with Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop, and Beth in Little Women continued with Jenny in Love Story and Billy in The Champ. (Have you watched that scene from The Champ, by the way? Little Ricky Schroeder just tears your heart out and then drowns it in his little-boy tears.)

In the late 1800s, the new technology of photography made it affordable for the nation’s new middle-class to have portraits made of their dead. Memorial photography was, in essence, proof that a “good death” had taken place—no matter how awful the actual experience had been. The dead could be posed in positions of long-awaited rest—eyelids shut, hands placed peacefully on chests. These mementos, taken out and looked at again and again, shaped families’ final memories of their dead, and often they were the only visual depictions of their loved ones people owned. Survivors hung them prominently in their houses and carried them around in lockets. They were proud that their son/daughter/mother had died well. That death was the capstone of a life well lived.

Which brings us back to today.

Oana Hogrefe’s memorial portraits are almost all taken in hospitals, but you can’t tell that from looking at them. They’re close-ups, and in each, all you see is a parent and the dying or deceased infant locked together in intimate connection. A head against a chest, hands on impossibly small hands, but no wires and no monitors. Sometimes you can see the faint impressions on infant skin left by tubes that have just been removed. Sometimes these are parents’ first experiences of holding their infants without them. It’s also their last. Like early memorial photography, Oana’s photographs are dreamlike images, stamped in film, of trauma erased.

There’s another parallel, too. These are usually the only photos of their infants these families will own, the only evidence of a relationship brand new but marked by all the hope and attachment of any parent. In essence, these photos serve as evidence that this relationship matters. This person lived, they declare. They also say, This person died. In the book, Oana tells me a story of a surviving twin who will later be able to look at the photo taken with his deceased sibling, and see: This was real. There we are together.

Before I met Oana, memorial photography in any form had seemed the very definition of strange. Why? Because who wants to think about death on purpose? Who wants to remember someone they love as dead? But now I saw the peace these photos brought those who were left, and I began to understand the motives of the sad-eyed mother holding her daughter in 1890 and those of another mother in 2004.

Memorial photography is sad. It does focus on death—something most of us 21st-century Americans just don’t do until the moment we have to, and even then, the experience isn’t just sad. It’s often alienating. Even though death is the only guaranteed appointment in the datebooks of our lives, and grieving the next one penciled in, our culture does little to prepare us for that. We have our pick of violent movie deaths to watch, but the heyday of the deathbed scene is long gone. For one thing, it’s fairly sentimental for 21st-century tastes, and for another, it’s unrealistic: Who dies at home anymore? These days, our deaths are usually handled at hospitals, nursing homes or other institutions, by professionals who do not know us.

This was the familiar made strange. We’re blessed with excellent medical facilities and the germ theory, but these do not stop death. And when a loved one does die, which is odder? Death at home surrounded by family who is then excused from all social duties for up to two years? Or death handled by strangers, and family members taking a few days or a few weeks off from work, after which they’re expected to return to life and behave just like everyone else? We can call the Victorians death-obsessed all we like, but this generation is downright death-phobic.

And that includes me. Because sure, I’m a nerd who enjoys treasure troves of weird facts, but I’m also a nervous human being who has not yet experienced real loss. So in this book, I collected the stories of people who had, and those who had shepherded people through it, in order to gain some sliver of the familiarity that life had not yet taught. The woman tending a roadside memorial for her daughter, the family holding a memorial weenie roast for their son and brother, the nineteenth-century widow sweating over strands of hair making a piece of hair jewelry—None of these had the answer, I knew that. But for matters without easy answers, we tell stories and we listen, in hopes of making the strange a little less so.