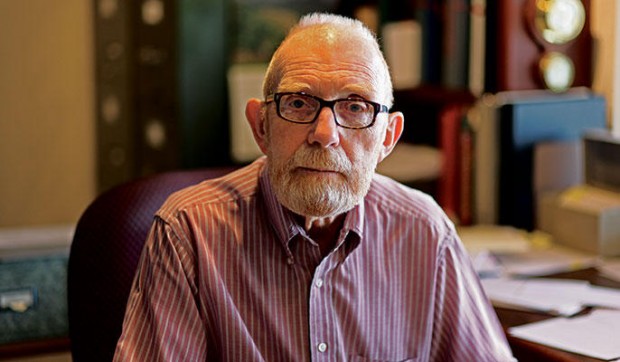

Guest contributor: Mac Bates

Farewell to Ivan Doig, Another Great of the American (North) West

categories: Cocktail Hour / Reading Under the Influence

5 comments

Growing up in the small town of Snohomish in Western Washington in the 1950s, it often felt as if the rest of the world had forgotten about us. Mountain ranges, desert and plains separated Northwesterners from the white hot center of culture in New England, and its glitzy pop cousin, Los Angeles. And Eisenhower’s dream of interstate freeways connecting us all, was 15 years from being realized. Not that I didn’t feel the pull of the world out there as I sat in the Snohomish Theater, transfixed by Around the World in 80 Days or staring agape as a young Elvis pretzel twisted his hips and sneered on our teeny-tiny TV, or tuning in to San Francisco’s KGO at night to listen to Ira Blue at the Hungry I as he birthed talk radio. But it seemed that in the Northwest we were free to invent ourselves. Thank God for parents who allowed us almost free rein to explore the Pilchuck River, or on one Sunday afternoon, to walk across the Snohomish River Valley on the railroad tracks to hunt for fossils at Fiddler’s Bluff; had a train come while we were on the last high trestle, we would have had a tragic Stand By Me moment. And to the east, the glacier-carved valleys and peaks of the Cascade would soon become an even larger playground. Our earliest jobs were outside, picking strawberries and raspberries and later wandering behind trucks in the pea fields with pitchforks or milking cows.

There was no Northwest cultural tradition to speak of. There was Mark Tobey, Imogene Cunningham, Gary Snyder, Betty McDonald, Bing Crosby, Quincy Jones, and Gypsy Rose Lee, but they fled the state at the earliest opportunity. There was no opera, no ballet, no theatre, and the Seattle Symphony, our lone connection to the arts, would often play in the echoey Snohomish High School gymnasium to disinterested farm kids. As much as I loved my home with its gray wet, salty water, Doug Fir forests, and especially the ragged, snowy peaks, I yearned vaguely for something that spoke to me of my northwest, something I couldn’t ever quite articulate. It would happen for me in books.

In college I worked much harder reading Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion than I ever had for any class. I mean, all those pages of hallucinatory dreamy stream-of-consciousness was head-melting, but Hank Stamper, standing against the bastards, chopping down trees, now there was an anti-hero I could get behind. Shortly after, Tom Robbins turned the Skagit Valley into a rain-soaked mystical other-world in Another Roadside Attraction. Then I chose a book at the University Bookstore because it had trees on the cover, what the hell? It was Norman MacLean’s A River Runs Through It, which I have read more times than any other book. And always I saw my father whenever Norman’s father cast his line into the Blackfoot River, as if it were a sacrament. Another Montanan, James Welch wrote Winter in the Blood, which laid out a young Native American’s tortuous psychic journey for understanding and dignity, in a country that seemed hell-bent on muddying understanding and stripped dignity away.

My antipathy to poetry was blown away by Richard Hugo’s What Thou Lovest Well Remains American, David Wagoner’s Collected Poems, and William Stafford’s Stories That Could Be True. There was so much generosity in Hugo’s poems even as he chronicled the lost lives of sad losers; Wagoner’s quiet contemplation in moss-covered forests, along snow-melt streams; and Stafford’s poetic conversations with the reader.

These were Northwest voices, strong and true and I carried them with me wherever I went, and they lent muscle to my arguments for the specialness of my place in the world.

Central to all these writers was the land, land that nurtured, inspired, bedeviled, haunted, trapped, ruined and transfigured. It was land without the gauze of nostalgia, but swelling with the ache of memory.

The last writer I came to was Ivan Doig, whose This House of Sky introduced me to the modern memoir, not to mention the Montana big sky, which I would not believe until I moved there in the late 1980s. It is blue and it is infinite. Doig wrote of a childhood spent with his itinerant ranching father and grandmother. It is a rough life, herding sheep, blistering in the summer, frigid in the winter, the wind a constant. And though it might seem like a lonely life for a boy, he had the company of cowboy characters he met on the ranches or in the bars, where from the age of six he became a regular with his dad: people with names like Bowtie Frenchy, Hoppy, Deaf John, Mulligan John or Long John. These characters I believe came to populate his novels, people dependent on the land, in touch with the land, and inextricably tied to the land, more than to any people in their lives. It is a tale of hardship and love. Doig, realizing that his father’s wanderlust would never be his own, came all the way out to settle in Seattle at the same time I was a young boy in Snohomish. And there he stayed until he died this April at age 75. I have not returned to Doig, although at various times I have had around the house Winter Brothers (My friend Jim says that’s the one), Dancing at the Rascal Fair, English Creek, and Ride With Me Mariah, Montana. There was something slightly loopy about his sentence structure, convoluted and awkward. After rereading This House of Sky I find his sentences to be delightful little winding rivers of words, and I am going to catch up on all things Doig this summer.

Today, there is a whole new generation of Northwest authors/poets writing wonderfully about a changed landscape, to be sure: Timothy Egan, Kim Barnes, Molly Gloss, Jess Walters, Sherman Alexis, Pete Fromm, David Guterson, John Krakauer, Deidre McNamer. Writers have discovered the Northwest, and we are ground zero for connectivity. Parents don’t let their kids explore Snohomish unless it’s an organized field trip. And while our citizens value the land, they are hell-bent developing it, all the way to the foothills of the Cascades. At least we have the work of Doig, MacLean, Stafford, Welch, and Robbins (still feisty and writing in his early 80s) to connect us to varied landscape that makes the Pacific Northwest special, a landscape that inspires me every day.

Mac Bates is a writer, teacher, and mountaineer who lives in Snohomish, Washington

Doig will certainly be missed. He was a representative voice from a generation that thought deeply about, and cared deeply for, the meaning of “place.” His writing allowed me, at least, to ponder the significance of my interactions with the natural world.

I’ll be teaching Doig (along with Snyder, Kesey, McLean, and many others mentioned here) in an upcoming fall graduate seminar — thanks for these thoughts, Mac, which have jump-started my thinking in that direction.

[And I’m sure you meant Sherman Alexie, not Alexis.]

I would love to take that class Sheila, and, no, I was referring to Sherm Alexis, and who will ever forget is bittersweet novella, “Walleye Walleye: a fisherman’s tale.”

Head-melting–lovely phrase.

Enjoyed this so much, Mac. It’s going to take me a moment or two to read this list, but wow, everything sounds wonderful. And Eisenhower’s dream. Now that was a good idea! Hard to imagine not being able to cross the country in a car, my family did so much of that–Roosevelt’s National Parks often the destination.

A book for you–The Meadow by James Galvin. Gorgeous! Set on the Colorado-Wyoming border–my neck of the woods.

Debora, I have ordered Mr. Galvin’s book. Thanks for the suggestion.

Galvin is terrific. He is married to the poet Jorie Graham…