Dave’s Jungle Adventure! (Really!)

categories: Cocktail Hour

8 comments

DUNGO IN THE JUNGLE

“Now the spoiler has come.” Robinson Jeffers

They were poaching deer and drinking dark rum out of a decapitated spring water bottle, Dungo and his friend. In the front seat were two shotguns–Dungo’s 12 gauge–he’d re-welded the barrel himself with bronze–and his friend Lilpo’s 16 gauge that looked like a Civil War musket. In the back of the truck lay two rusted machetes (pronounced with two syllables–ma-chet–in southern Belize.) Lilpo thought he saw a light far down the trail and so Dungo drove in further over the bumps and ruts, though he didn’t see it himself. But as they got closer, they were sure they made out two or three flashlights.

As it turned out we were the ones waving the flashlights. They stopped twenty yards from us and called out.

“Jake?” I yelled back. Jake was the name of the man who ran the research station we’d been scheduled to hike into that day. We’d been lost for several hours so I thought he might have come looking for us.

“No, it’s not Jake, man,” Dungo yelled back, already laughing. He pulled the truck up to where we stood.

I later teased my wife that she ran up to them as if they were Triple-A rumbling up the interstate: “Oh, thank God you’re here! We’re Americans, we have money!” My friend Mark, for his part, greeted the truck’s arrival by lying down in the mud on the side of the road, the last of his energy spent. By default, it was up to me to play the part of the paranoid; I wasn’t quite so sure we were being saved.

“You want a drink, man?” the driver asked me, holding out the rum.

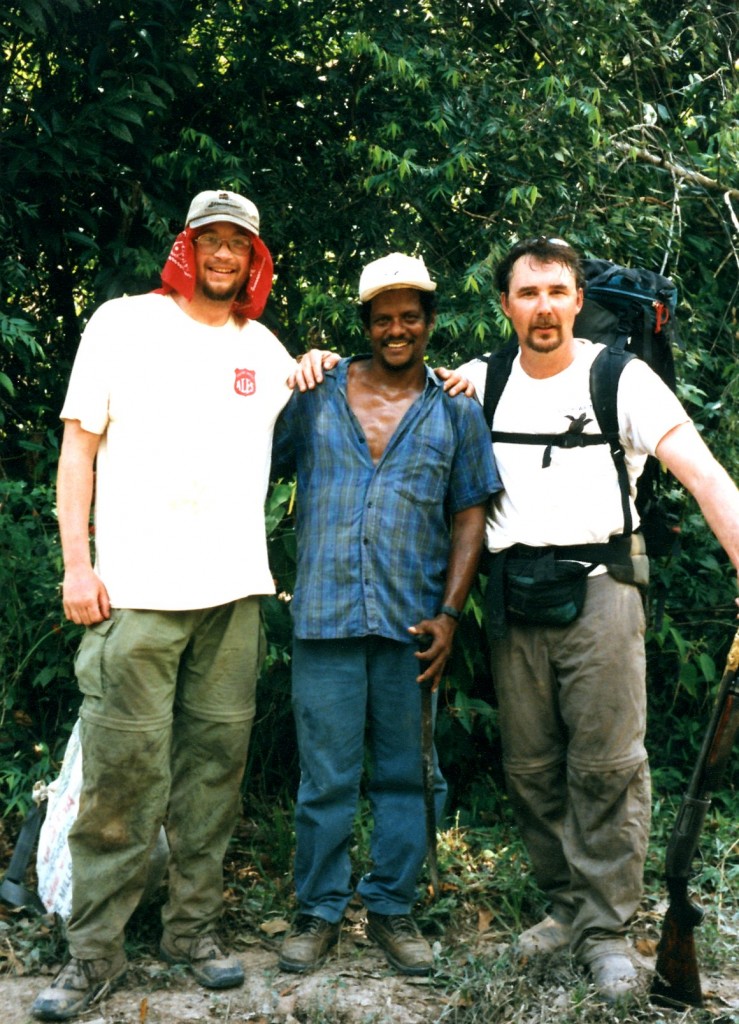

I declined and began to explain our situation. The driver was a black man of medium height who told me his name was Edward, but that out here he went by what he called his jungle name: “Dungo.” Dungo had the distinct look of an Australian aborigine–“What I am they call a ‘Coolie’ around here,” he explained to me later when giving me an ethnic sketch of Belize; “Coolie” being a term for anyone with East Indian blood. He had a ready but wild smile, and a quick laugh. His friend Lilpo was taller–“A Creole,” Dungo said the next day–and more stoic, but his rasta hat seemed to hint at pacifism, despite the jutting gun. I offered them twenty bucks American to drive us back to the nearest hotel, and soon Nina, Mark and I had all piled into the bed of their truck.

What we were doing out there in the first place was another story. Stick to the road, our host had told us before sending us off on our adventure, and so we stuck to the road. Stuck to it when it suddenly veered south, parallel rather than into the jungle; stuck to it when it meant wading through knee-deep water and waist-deep grasses, despite all the snake-warnings we’d been given; stuck to it when it began to weave crazily in and out of the jungle itself, despite the increasingly obvious evidence that it was leading us nowhere. “Snakes love leaf litter,” our long-gone guide had warned us, but as the afternoon wore on leaf litter, specifically the perfectly snake-colored dead palm fronds, was all we walked over. It said everything you need to know that when a six foot diamond-patterned  creature the thickness of an engorged firehose lay in our path, we quickly dismissed it as “only a boa constrictor,” shrugging off the largest uncaged reptile I’d seen in my life as if it were a gray squirrel.

creature the thickness of an engorged firehose lay in our path, we quickly dismissed it as “only a boa constrictor,” shrugging off the largest uncaged reptile I’d seen in my life as if it were a gray squirrel.

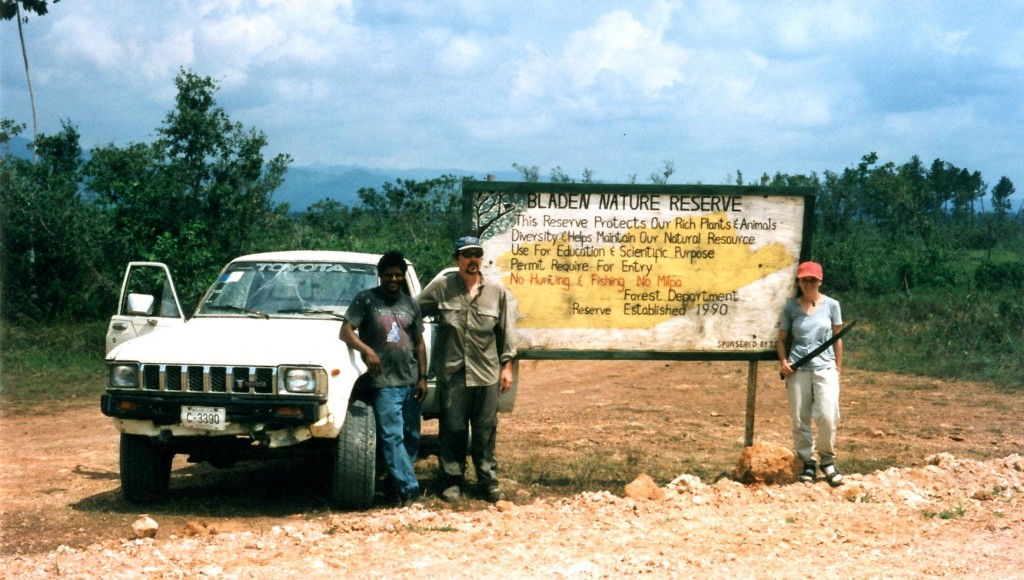

There were three of us hiking into a biological research station in the most remote jungle of Belize–me, a momentarily displaced New England nature writer, my wife Nina, also a writer, and one of my closest friends Mark, who, it was slowly dawning on me, wasn’t quite the young, Ultimate Frisbee-playing jock I still imagined him to be, but was, in fact, an out-of-shape middle-aged man with pale skin never meant to be exposed to the equatorial sun. In other adventures–lost and water-less in the Utah canyonlands, carrying a burning crib (really) full of newspaper and kindling out of our home on Cape Cod–Mark had acquitted himself quite heroically, and he was by far the most survival competent of the three of us, having been given instructions by our former guide to “watch out for Nina and David.” But this would not be his finest hour. By mile two of our hike into the Bladen Nature Reserve, the brown jays scolding down at us, he was already grumbling and stumbling across the pine savannah, the rain forest still some ways off, the Maya Mountains shimmering in the West. When we veered south he began to mutter about the idiocy of the trailmakers. In fact he was sensing correctly that we were going the wrong way, but I just wrote his warning off as more griping. He did perk up briefly when he saw the seven inch jaguar print in the fresh mud, pulling a camera from the knapsack that held

twenty-five pounds or so of photographic equipment that he wore like a papoose hanging off the front of his chest. But by the time we started wading through the muddy water he was all but finished, not even reviving when, after three hours, the track finally seemed to begin heading in the right direction. In retrospect I understand that he was suffering from heat exhaustion, and having since been leveled by it myself, understand what an effort it took to move those many miles while sick, but a the moment I thought him a slacker. More and more Mark began to take unannounced breaks, lying down right on the trail, even on the dreaded leaf litter itself.

My own reaction to his condition, and our predicament, was a fairly perverse one: I was transformed into one of those fanatic conquistador-type characters out of a Werner Herzog film, complete with crazed eye gleam, convinced that we needed to push further and faster into the jungle despite the growing evidence to the contrary. The dynamic between Mark and me had been similar for a while near the end of the time we’d been lost in Utah, when I, pumped on adrenaline, had waxed poetic about the glorious rising full moon that seemed to be leading us home and he had snarled back: “Fuck the Moon.” In the jungle he barely looked up when I pointed out the swirling tornado of white and yellow–both pale and bright yellow with delicate white outlines–butterflies. He did manage to snap a shot of the boa constrictor, that, after posing for us, slithered politely off the trail, but when he sat down to rest again I decided foolishly that Nina and I should charge on without him. After another couple of miles the jungle closed in, the cahoon palms canopying overhead and the chatter of strange birds reverberating. The straps of our backpacks cut into sunburned and bug-bitten skin, slipping on a pool of sweat and slime. Nina called back to Mark and I blew hard on the whistle he’d given me, but there was no response. It was now past Four O’Clock and the sun would set at Six. Nina, the youngest and fittest of us, was also the voice of reason. “We can’t just leave him back there,” she said. “This path is going nowhere.” I had one last surge of Herzogian energy and charged ahead for another mile to discover that she was right. The path simply stopped, swallowed up by green.

It was around this time, the sun starting to drop over the mountains, that we remembered that the most deadly of the snakes we had been warned about, the Fer-de-Lance, which was nocturnal and was likely just yawning itself awake. Later a herpetologist would assure us that the Fer-de-Lance, or Tommygoff as it was known locally, was not “aggressive,” as the guide books all claimed, but was in fact merely territorial, but at the time we knew nothing but what we’d been told. Nina and I turned around and began to backtrack out of the jungle with a new and desperate energy. As it grew dark we walked even faster, crunching over fallen logs and occasionally tripping, leaf litter be damned. By the time we got back to Mark it was clear he was not merely malingering: he was sick, a case of heat exhaustion at the least, and I’d never seen him so lifeless. We lugged him to his feet, and Nina

took his camera pack, divvying the contents up between the two of us. We set short term goals, the first and most urgent being getting out of the jungle before dark. When that was done we briefly considered setting up camp, and began gathering wood and taking our packs off, but that idea was squelched by the look on Nina’s face and the notion of spending a tentless night with the jaguars and fer-de-lance, not to mention the bugs. And so the forced march continued, the next goal being getting back to the water we’d hiked through. In a day full of worst moments my very worst might have been sloshing through two feet of brown water in the dusk, smacking a large stick in front of me to ward off snakes, while my boot was sucked off into the muck. I dug the boot out, and we plowed through the water, but once we got to the other side we all collapsed in the hump of mud between two deep tire tracks of water.

On the back of Nina’s pack she still carried the pineapple she’d strapped there that morning. We considered slicing it open, but finally decided to save it for dinner. By that time we’d been hiking seven and a half hours and were out of water, but Mark’s bottle of warm Coca-Cola gave Nina and me new life as the light faded and dozens of swallows carved up the insect-filled sky. At the point where we’d made our wrong turn we stopped and listened to the wild mockery of laughing falcons, a noise that my field guide rightly described as being like “maniacal laughter.”

It was dark by the time we’d turned back West, with three miles to go to the highway. “Highway” here is a loose term to describe a bumpy dirt road with little traffic. That morning we’d been driven two hours from the biological camp where we’d been staying and dropped off at the sign for the Bladen Reserve. We had no assurances that getting out to the road would be our salvation, or even a particularly good idea, trading the reptilian threat for the human one, but Nina was now sure of one thing: she wasn’t sleeping outside, at least not in this place. So we trudged on, our flashlights reflecting back the eyeshine of our audience, the many animals watching us from the sides of the trail. With the sun down, Mark mustered up a new surge of life and was now moving at a steady clip. I walked out front, smacking my stick on the trail, channelling some ancient tribal song meant to ward off snakes–“Snakes begone…Snakes go away…We kill snakes”–and singing loud, bad renditions of “Rumble in the Jungle,” “Jungle Love,” and, for no particular reason, “I Want to Rock and Roll all Night (and party every day).”

It was in this tattered, ridiculous state that we suddenly thought we saw a light, suspecting wrongly that we’d made it out to the highway. After a second of readjustment, we realized our mistake. The light was coming down the trail itself–headlights, we saw now. An old battered truck was rumbling toward us.

* * *

We must have looked ridiculous as we lay there in the bed of Dungo’s truck. It was a scene I later tried to draw. Mark lying down flat, all 6’4″ of him, his head by the tailgate resting on his pack, next to an uncovered cooler full of fish, snappers that Dungo had caught in the Monkey River earlier that day. Nina up by the cab unknowingly leaning on Lilpo’s machete as we bounced out along the trail, with me next to her, sitting on a bag full of corn and leaning in the window to the cab, keeping up a steady stream of conversation with Dungo, still not entirely sure if he was friend or foe. Maybe I’d read too much Hemingway as a teenager, but I slipped Mark’s fillet knife out of his pack and under my belt as I crouched and leaned into the small window. We discussed the various hotel options and then Dungo said: “We just got to go drop Lilpo off at his farmhouse first.” They talked in Creole for a minute while I tensed, imagining a long dirt road and our executions by shotgun. I suggested we head to the hotel first instead.

“No man,” Dungo said. “It’s right on the way.”

And it was. After we’d dropped Lilpo off, and continued down the Southern Highway, I relaxed and gradually began to see Edward for what he was: a generous, and exceedingly gregarious, man. I took the pineapple we’d carted in off of the back of Nina’s pack and sliced it with the filet knife. You haven’t eaten a pineapple until you’ve eaten one in the tropics, and this might have been the greatest pineapple ever. Mark, Nina, and I ate it all, slice after succulent, dust-covered slice.

We drove to Independence, a small town of dirt roads and shacks with corrugated tin roofs, many of them blown off by the hurricane back in October. A scrawny dog with low-hanging teats jogged down the middle of the road as if interested in a game of slow-motion chicken, swerving out of the way after Dungo hit the horn. We pulled into a cinder block building that didn’t look like a hotel, but Dungo took care of us. Soon he’d helped us carry the bags upstairs, helped me cut a deal for less than the usual price, and told us we could find him later at the bar across the parking lot. Even before we got lost our trip hadn’t been a very tourist-y one, mostly hanging out with ornithologists and botanists, but now, in a perfect counterpoint to the day, we discovered that the “Hotel Hello” was the single most American place we would stay. The room had two queen sized beds; it was air-conditioned with cable TV and, for the first time that trip, hot water. Mark lay still but shivering in one of the beds for a while, but began to stir after about a gallon or two of water. I brought up a plate of fried chicken and soon we were lying down on the beds, admiring our torn up feet, and gorging on chicken, watching “Blind Date” and “Rendez-view” on the tube.

The bar I found Dungo in was equally modern. Five Belizean and one white English Banana sales rep were staring up at Schwarzenegger in “True Lies,” cheering on the preposterous closing helicopter scene. A poster called “Ten Ways a Beer is Better than a Woman” hung on the wall. Dungo slapped me on the back and began to tell his barmates about our escapades. I admitted that I hadn’t been sure at first if Dungo was there to kill us or save us, and everyone laughed. Over the next hour I bought us each three Belikins, the national beer, and soon we were re-telling our jungle adventures with the over-hardy air of drunken camaraderie. Like me, Dungo was a talker, and he knew everyone in the bar. Soon I’d learned about his career as a truck driver who sometimes drove up to the U.S., his days as an apprentice in the bush, his plans to expand his home for rentals, and the hurricane’s disastrous effect on those plans. In the course of that hour I asked Dungo if he would be our guide for the rest of the trip, and he agreed for a reasonable price.

We were in business.

TO BE CONTNUED

Almost epic! Once again, bonds are forged via the international language – BEER!

Those are bitchin’ blisters. I say, stay at the hotel!

I thought we were supposed to call it the rain forest now.

Well I guess I’m just old fashioned…….and it seemed like that’s what people there were calling it.

Great story. I beat you there. I paddled the Macal River in ’78 and ’79 on a crocodile survey. Now it’s under a stupid lake.

What was that, yesterday? 😉

Eli…I don’t get this…. But I want to and I’m sure when I do I’ll nod my head at your wisdom/humor.

Aah so that is the famous Dungo from Sick of Nature!