Caught in Cuba

categories: Cocktail Hour

2 comments

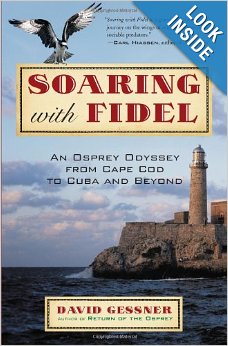

The following is a small excerpt from my book, Soaring with Fidel. The book follows ospreys as they migrate from their summer homes on Cape Cod to their winter ones in South America with a stopover in Cuba on the way. The birds require no passports to do this, which is more than I can say for me. My own trip landed me in hot water with both the Cuban government and my own. After a week in Cuba I was ready to head home when the following occurred:

The following is a small excerpt from my book, Soaring with Fidel. The book follows ospreys as they migrate from their summer homes on Cape Cod to their winter ones in South America with a stopover in Cuba on the way. The birds require no passports to do this, which is more than I can say for me. My own trip landed me in hot water with both the Cuban government and my own. After a week in Cuba I was ready to head home when the following occurred:

I was about to carry my bags to the cab when the manager came out of his office and walked up to me with a piece of paper. It was a ticket, a summons from the immigration office inSantiago. My plane left in two hours and I had been told to be there early. I felt a mild panic rising.

“It is not uncommon to get this kind of ticket,” Freddy said calmly. “And the office is just a kilometer away.”

He volunteered to accompany me, but the directions sounded easy enough. Rather than take a cab, I headed down the street on foot, carrying my backpack and suitcase. The streets were crowded, and I watched as a commuting businessman with a briefcase climbed up into the back of an old truck with two dozen other men. When I got to the address on the ticket there were just a series of rundown houses, nothing that looked even vaguely like an office. I stopped a woman holding hands with a five year old boy, and asked where the immigration office was, and she said the office had moved and pointed down the street, making a leftward sweeping motion with her hand. I took the street and the left, lugging my bags, and found nothing except another crowd of people. The next two strangers I questioned offered up completely different answers to my query and by then I was covered in sweat and tamping down a deeper panic. My trip was over; I’d seen my birds; I wanted to go home. But instead I was walking through the crowded maze of Santiago, lugging my luggage, sweating through my clothes, and getting different directions from every person I met. Finally I found myself standing at the door of a yellow trimmed Victorian home–no doubt the home of a wealthy individual before the Triumph of the Revolution. Though there was nothing to identify it as the immigration office, a man out front assured me it was. Inside a grim-faced woman told me to wait in the hall and then returned to her wooden seat behind a small desk. She was typing out a form on an ancient typewriter, filling in answers given by a woman sitting across from her. An old, creepy feeling came over me there in the dark hallway, one I barely remembered despite the impact it had on me at the time–that of being called to the principal’s office as a kid. My hair and Hawaiian shirt were drenched in sweat from the walk and I couldn’t imagine the principal was going to be very impressed. I pictured my plane leaving and my being stuck in Cuba with my money running out.

Twenty minutes later I was in another room sitting in a hard-backed chair across from two women and a scary-looking man in a suit and tie. The scary guy asked for my passport and I handed it to him. One of the women wrote down everything I said, and the other explained that she was there as a translator. The translator looked friendly enough but her English was not much better than the bad Spanish I had learned back in Senor Shepherd’s class in high school, and so the interrogation took place half in Spanish, half in English. The questions started: What do you think of Cuba? Me gusta mucha! Have you talked to people about the government while you were here? No, no! Did you take only official taxis? Si, si.

As the questions continued, the scene grew more creepy and Orwellian. But at the same time it still partly felt like a game, like when I was in college and was pulled over by the college cops, not the real cops, after tearing down a street sign as a prank. These people had stern looks on their faces but that had to be perfunctory, right? I had a feeling that it would all end well.

And then that feeling passed.

Why did you go into the mountains?

Here is where I thought I could really win them over.

“Porque me gusta mucho las aguilas pescadoras. Yo escriben una libre de las aguilas. Parame las agilas es muy importante….”

And so on and so forth in my mutilated Spanish trying to explain my love affair with ospreys and the books I had written, and would write, about them. What could be more winning? Who wouldn’t love the story of a simple guy who loved birds–innocent little birds? Caught up in the momentum of my story I painted a picture of a future when people from all over the world would flock to La Gran Piedra to see the great river of ospreys.

But strangely, instead of smiles and nods, the three brows across from me began to furrow and the three heads nodded sternly. I had meant my spiel to sound enthusiastic but now I worried that perhaps it had carried a whiff of fanaticism. Finally the man in the suit spoke to me in the English, a language that I hadn’t realized he understood.

“In our country, this is not allowed,” he said. “You can come for tourism in our country, but not for birds.”

A cartoon lightbulb went off over my head. Instantly I became a sixties sit-com husband who, caught in a lie to his wife, furiously backpedals.

“But birds are my tourism,” I said, deciding to stick mostly to English now. “It was all just for fun. Touristo!”

The man scribbled something else down.

“Did you meet any people up in the mountains?” he asked.

“I met people. But it wasn’t deep. Just hello.”

With that he got up and walked out of the room carrying my passport. A second later the stern woman stood and followed him. The translator just sat looking at me. She shook her head slowly and sadly. She said: “To work here you need a visa.”

We sat there for ten, fifteen minutes in silence. Visions of Hadley and Nina and home swirled in my head. I wished I could beam myself back to the United States, or like Castro on the Granma, wished I could fly. I looked down at my watch and mentioned the time of my flight to the translator. She stood up and left the room, and I sat alone for another fifteen minutes.

This was long enough for me to dissolve in a puddle of sweat, sweat that now came from both my walk and my panic. I wondered how I would stand up to torture and decided the answer was “not too well.” But then suddenly the translator was walking back in, wearing a smile and waving my passport. She sat down and then leaned toward me and patted my leg.

“It will be all right,” she said. “They are just calling the airport to hold your plane.”

She asked me if I had any children and I pulled a picture of Hadley from my wallet, and by the time the other two returned we were having a great time of it talking about our kids. In a spasm of relief I went on about how Hadley was learning to talk while I was away and then she started to describe her two girls, one older and one younger than Hadley. Then she interrupted herself.

“We must stop now for you to catch your plane,” she said. “You had better hurry.”

* * *

A direct flight from Santiago to North Carolina is, as the osprey flies, about eight hundred miles. The tagged osprey, Tasha, could do it in two days with the right tailwinds.

It took me longer than that to get home. First it was back to Havana for a night and then to Cancun for most of the next day. In HavanaI spent the night in the same crappy hotel, and wondered again how that city had achieved its romantic reputation. Maybe I was just in the wrong part of town, but in my mind the city paled next to la Gran Piedra. The bed was uncomfortable, the room hot, and after I finally fell asleep in a pool of sweat I was awakened by a great roar coming up from the streets. The next day I would realize that this was not due to some great rally for the glory of the Revolution but because the Yankees, the dreaded baseball Yankees, dire enemies of my Red Sox, had won a playoff game in extra innings. Thanks to their Cuban players, especially El Duque, the Yankees were a local favorite.

The next day was spent flying from Havana to Cancun, where I passed an unpleasant six hours in the airport listening over and over to a recording of a woman’s voice, apparently the same one used worldwide, repeating “Unattended vehicles will be ticketed and towed” in both Spanish and English. My nerves were shot from the interrogation and travel, and I was both longing to see my family and dreading dealing with American Customs. Though I didn’t have a stamp in my passport, I had two stamps for going both in and out of Mexico through Cancun, and that would take some explaining. I had decided not to lie about where I’d been, feeling it was better to take whatever penalties they were doling out than to perjure myself.

Even though I was nervous, a part of me, the writer part, sort of hoped that the interrogation in the United States would mirror the one in Cuba, just for the poetry and symmetry of the thing. But the truth was that, even in the age of Bush, I never felt quite as worried when they questioned me in Charlotte, in part because I was in my own country and in part because it all took place in English.

Once I admitted I’d been in Cuba I was shunted off toward a desk where a chubby black woman in uniform stood. She took my passport and asked me if I knew that it was illegal to travel to Cuba.

I said I was a journalist and a researcher and that I believed I qualified under the general permit.

“There is no longer any general permit,” she said sharply.

She asked a dozen more questions and had me fill out some forms, but the truth was she grew friendlier as we talked and I never felt the real fear that I’d briefly experienced in Santiago. The only creepy moment was at the end, after she had handed back my passport.

I said goodbye and she said the same. But then, as I was walking away, she spoke a line I thought people only said in movies. She was not a particularly impressive woman but she delivered her line impressively.

“They’ll be in touch,” she said.

Some nice things people have said about Soaring with Fidel:

Soaring with Fidel is a grand and cheering journey on the wings of one of nature’s most sociable predators. It’s impossible to watch an osprey hovering above a crystal calm bay and not envy the great bird’s freedom. Now, thanks to David Gessner, we are invited to follow. Carl Hiaasen

January 29 issue of Publishers Weekly

At the outset, Gessner tells readers that “[t]his is not a bird book”; indeed, it’s more about what Gessner came to understand about himself by spending day after day studying one particular species of bird, the osprey. Gessner, who previously wrote Return of the Osprey , which focuses on the effort to rescue ospreys from DDT annihilation, this time turns his attention to migration-why ospreys migrate to Central and South America every winter, and what they do when they’re there. He tracked ospreys on one basic migration route-from Cape Cod to Cuba and back. While Gessner weaves in the science of tracking the birds, it’s his rowboat-and-binoculars approach to the subject that will most attract readers. Spending days watching ospreys and chatting with other bird-watchers, Gessner discovers the “joy in reducing life to one thing.” Gessner writes beautifully, with grace and humor.

January 15 issue of Kirkus

One man’s serendipitous adventures and misadventures as he follows the annual southern migration of his favorite birds.

Longtime osprey observer Gessner (Creative Writing/Univ. of North Carolina Wilmington; Return of the Osprey, 2001, etc.) began his journey on Cape Cod in September 2004. Armed with the usual birding equipment, plus a cassette recorder and journal for recording his impressions, he seems to have also taken along Lady Luck as a traveling companion. On a tight budget and schedule, he was repeatedly given advice, directions to good sites and even room and board by fellow birders he met along the way. While focused on the behavior of a particular species, this is also about birders and their highly competitive sport. The author himself was in competition with a British television crew that was tracking five ospreys on their southern migration with the aid of a satellite and sophisticated telemetry. One osprey, dubbed Bluebeard by the Brits, Gessner renamed Fidel, hoping he would see it in Cuba. Getting to Cuba was an adventure in itself, as was getting around the country once he arrived. The author went back to North Carolina for a brief stay with his wife and daughter before setting out for the jungles of Venezuela, taking along as a sort of bodyguard a friend who resembled “a large, hairy scarecrow.” Much beer and many birds later, they returned home safely.

Gessner’s account is filled with nitty-gritty details about the days and nights of an itinerant birder and beautifully detailed descriptions of ospreys in action. When actual observations were not possible, he imagined what the ospreys were doing and writes intelligently of that. In the final chapter, while summering on Cape Cod, Gessner learned that Fidel had been tracked back to Martha’s Vineyard, and it was there that he got to see his special bird.

A grand adventure, not just for birders and nature lovers.

I haven’t read this book, but this sounds interesting. I have often thought of traveling to Cuba from Latin America, but never followed through. Enjoyed reading this snippet of your perils (and you left us at a place where we will have to read your book to find out what will happen!). -Jeff

I enjoyed this book. Especially the part where you found themall wintering around a lakei in enezuela, I think., and then, the meal your character, Honerkamp, ate. Or was that at the Gulf!? It was also fascinating to learn how the migratory birds all back-up at Cape May, I never looked at water and land like that before.