Guest contributor: Alise Hamilton

Bad Advice Wednesday: To Binge or Plod?

categories: Bad Advice / Cocktail Hour

5 comments

As literary crushes go, Aimee Bender is definitely in my top ten. I discovered her short stories as an undergrad—the first one I ever read, a bad photocopy of “The Healer,” featured a girl with a hand of fire and a girl with a hand of ice. It was bursting with two of the things I value most in fiction: imagination and heart. I was hooked.

So of course I read Aimee Bender’s recent article, “Why the Best Way to Get Creative Is to Make Some Rules,” even though it was categorized in the “spirit” section of Oprah’s website, and even though a banner of three white women hugging and smiling, the text glowing “Empower Yourself” floated at the top of the page. Even though I find the word “rules” to be something of a turn-off, and am especially suspicious when the word is being applied to creativity.

In the article, Bender makes the case for maintaining a strict, daily writing routine, complete with set start and stop times, and even goes so far as to suggest drafting a contract. She makes her argument by citing psychotherapy and Hemingway, and by using words like “discipline” and “structure.” It is a method that has, without a doubt, worked for Bender. But the article isn’t meant to be a peek into her writing process; it is a call to action.

Bender’s counsel will not be unfamiliar to anyone who has studied, or even dabbled in, writing. Developing a daily writing routine is a widespread piece of craft advice, one given especially to novice writers. Bender goes on to say:

With all its wonderful bureaucratic stick-in-the-mud specificity, the contract is then also a fighting gesture against the ever-present idea that writers walk around with alchemy boiling in their fingertips. That we are dreamy wanderers carrying a snifter of brandy, with elegant sentences available on call. It’s such a load of crap. Sure, there are writers who work this way, who embrace their writerliness and are still able to get work done, but most I know have found their voice through routine, through ordinariness, through some kind of method of working.

The writers who keep a daily schedule—let’s call them Dailies—often take this tone of superiority to writers who work in fits and bursts, who have long stretches of no writing followed by intense periods where they do nothing else, sometimes forgetting to sleep and eat. The Bingers.

The language between Bingers and Dailies is reminiscent of the Mommy Wars. The Dailies fancy themselves disciplined and dedicated. They have conviction. If they happen to have day jobs or children—or both—then they are doubly superior. They make sacrifices. They practice “a method of working.”

Which is to say, or at least imply, Bingers don’t work. They are the “dreamy wanderers” with their brandy and their bohemian tendencies. Like the Mommy Wars, each side feels the other receives more praise and admiration. Bender writes of the “ever-present idea that writers walk around with alchemy boiling in their fingertips.” And yet Bingers are often painted as less serious and less authentic than their structured comrades. Among other writers, Bingers are mostly in the closet lest they be painted as frauds merely wanting to look like writers, of not putting in the time.

I’ve lied about being one of the Dailies for quite some time.

“Do you write every day?”

“Oh yes,” I answer, indignant that there was even a question. Of course I write every day! What do you take me for?

In fact, there was a time where I did write every day. I thought that to be a “real” writer, I must. (What is this preoccupation was being “real” with writers, anyway? Like we are a bunch of wooden puppets praying for the Blue Fairy to visit us.) I was guilted into developing the habit. For three months of so, I showed up at my desk, every day, for at least thirty minutes. During this period, I spent a lot of time staring at the wall and fidgeting in my chair. I would write a few awkward sentences and then put my head in my hands. I would never be a real boy writer!

Finally, I gave up and went back to my messy, disorderly ways.

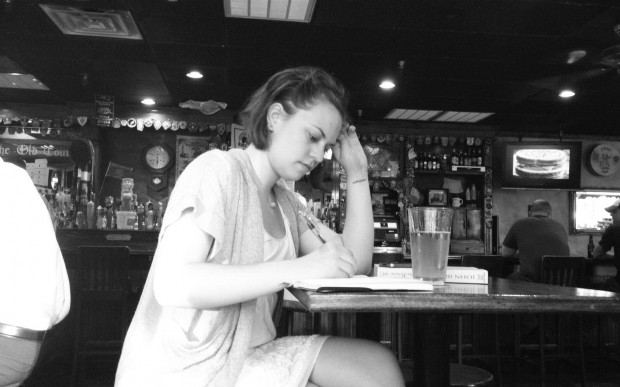

The trick to binge writing is that, unbeknownst to others (or maybe even yourself), you are “writing” even when you are not. Before I start a new story or project I spend days or even weeks letting it tumble around in my head. I do most of my writing while walking, “dreamy wandering,” if you will. Once I went for a walk in my neighborhood, looked up, and realized I had no idea where I was. I write while I’m driving, I write in the shower, I write, sitting very still with my cat in my lap on the couch, staring off into space. The story builds and builds until I feel like I could just boil over, and when I go to sit at my lap top—which could be anywhere, by the way: my bed or the kitchen table, a noisy coffee shop or my couch—I need to know I have a long stretch of time ahead of me. I need my calendar cleared; I need to have nowhere to be. I enter into what psychologists call “flow,” a mental state in which time disappears and I am fully immersed. Flow is, supposedly, the ultimate state of happiness.

Louise Glück, reading from her new tome of a collection, “Poems: 1962-2012” said she couldn’t believe how much work she had done. “I feel like I’ve spent most of my time not writing,” she said to a packed room at Harvard Bookstore in Cambridge.

Glück isn’t the only writer who has come out and openly admitted to not writing every day. In an interview with The Paris Review, Susan Sontag said, “I write in spurts. I write when I have to because the pressure builds up and I feel enough confidence that something has matured in my head and I can write it down. But once something is really under way, I don’t want to do anything else. I don’t go out, much of the time I forget to eat, I sleep very little. It’s a very undisciplined way of working and makes me not very prolific.”

Cheryl Strayed in an interview with 99U said, “I’ve always been a kind of ‘binge writer’ even in my waitressing days. After not writing for a few months I’d apply to a residency in an artist colony and just go and write for months.”

The very existence and artist colonies suggest that there are more Bingers out there than the Dailies would have you believe. Why go away for block of time if not to, hopefully, write in a great burst?

This is not to say that writing every day is necessarily a bad thing. There is a mystique and kind of superiority, too, to binge writing. Writing in bursts does not make one more inspired, does not mean you are closer to the muse. It does not make you more authentic. Frustratingly, and like most aspects of writing, there is no “right way.” You listen to other writers, you try out their techniques. Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t, but in the end, no one sees you working. In the end, it doesn’t really matter how you get there. When a reader come to your story, she doesn’t care how much time you spent picking at your cuticles instead of slamming away at the keyboard. She doesn’t care if it was night or morning when it was crafted. She doesn’t care if it took you one year or if it took you ten.

[Alise Hamilton is a writer and bookseller (Andover Books, Andover, MA), and she’s not kidding around.]

This a thoroughgoing and wise exploration of a conflict we’ve all experienced. I particularly like the examination of the implied morality and judgments attached to the writing process. It reminds me of the Christian distinction of whether you’re saved by grace or saved by works. I long ago accepted that people can consider themselves writers whether they’re a Daily or a Binger — yet, rational or not, I feel better about myself when I’m working in one of my Daily phases.

It’s not like you have to be one or the other, either. I have heard writers say they take on different tractics for different project, or just at different times throughout the years. Anyway, you’re right to say that the reader doesn’t care how you got anything on the page. Good essay.

A great essay. I once read an interview with Toni Morrison who called herself precisely that (a binge writer), and said she goes to a motel room and holes up for days. Funny that you mentioned artist colonies as evidence that there are a lot more Bingers out there than one would expect. I just returned from 8 weeks at The MacDowell Colony and noticed that there were a fair number of Daily types even in that intensive setting. While it’s true that everyone at places like MacDowell probably works pretty much every day, and real life doesn’t intrude, even there one sees a difference: there are the 9-5ers who take 3 meals a day and get a good night’s sleep and require fresh air and even a bit of healthy exercise, and then there are the red-eyed maniacs who throw themselves into the work and barely surface to shower. All a matter of degree, I suppose. For a binge writer like me, it was heaven. I even had time to bathe.

Wonderful stuff, Alise.

You’re right, I think; it’s wrong to talk about writing habits in anything but a case-by-case basis. What works for you works for you. I remember in school I would sit and research and outline and draft and draft and draft, and still get the same grade on a paper as the kid who never even created a word document until the day before the paper was due.

Even if I was a great writer, I wouldn’t try to advise people about schedules. If you do your best work standing in the shower, steam billowing up and around you, or staring into space while crunching on a Panera panini (which was me ten minutes ago), more power to you.

But I will share just what works for me. For me, the physical act of putting pen to paper steadies, reinforces, and encourages me. So for me, a screenwriter, writing doesn’t always mean opening up Final Draft and plugging away at two characters’ stichomythia. But it does mean always carrying around a tiny notebook and a pen. It provides me with the sense that I’m working toward some kind of end. It’s almost like when math teachers in high school would give you some credit for showing your work, even if the solution to the problem was wrong. Personally, if I have nothing to show for all my dreaming, I have a problem taking myself seriously. So I’ll just show my dreaming.

“I am a writer, see? I’m writing right now! What am I writing? Well, I’m writing about how I feel my career is a kite whose string is held by a selfish chubby kid. I don’t know, it’ll probably fit somewhere. But I’m writing, that’s the important part, right?”

And I need that notebook because honestly I don’t trust myself to remember things. So when I’m at a bar and my ridiculous friend says something that absolutely needs to be a line in a movie, or I’m at work and my hilarious boss (who could be a successful standup comedian) outlines a situation that could totally solve the tonal problem at the beginning of my romantic comedy, it won’t pass me by. Or when I’m lying in that surreal space between waking and sleep that some major life realization that thematically applies to my work visits me, I can capture it like a firefly in an empty tomato sauce jar.

(Yeah weak. Don’t judge me, I’m pretty hung over.)

So for me, even if I’m not knee deep in some sort of word processor, I feel I must write, in the literal sense. It helps.

What do you think?

Alise, I like this piece very much–I’m a binger and can say you describe me well. I have never found any point in writing until I have a collection of ideas that are important to me, and I love the feeling of being fully engaged in my creative spin, once I arrive at the writing-it-down place. This “you’re not a writer” energy you have noticed coming off people is definitely out there…and so interesting for what it reveals about them.

Speaking of picking cuticles, I forced my salon friends to read my last essay. Knowing one of them hates to read, I had hoped to impact that. I saw her yesterday, she said she was glad she read it because she has never learned to ski or snow board and now she knows what that is like. You are right, Alise. When a reader comes to your story, she doesn’t care about the crafting, she cares if there is something in there for her.

What is in “To Binge or Plod” for me is that I enjoyed hearing what other writers have to say about their own processes, and I think it’s a valuable concept to break down the idea that to be a writer means a given set of things that add up to some sort of certainty.