Guest contributor: Richard Gilbert

Bad Advice Wednesday: Three Lessons on the Path to Publication of My Memoir

categories: Bad Advice / Cocktail Hour

19 comments

I was fifty and the marketing manager of a university press when one day I decided I wanted to—had to—write a book. My own book. The story I needed to tell. There I was, bent over a drawer in the press’s endless row of gray-green filing cabinets, and from the radio perched somewhere overhead I heard a writer, a man my age, talking about his latest book. What am I waiting for? I wondered. I’d noticed that one of our recent authors had attended something called a low-residency program for her MFA. We were publishing what had begun as her thesis.

Slamming that cabinet drawer behind me, I headed for my computer to google her college. That’s what I’ll do, I thought. Keep my demanding day job, keep running our sheep farm on the side, knock out this book in a year, polish it for a year, and publish. I figured that picking up an MFA would be a nice bonus credential. Maybe I’d learn a few tips—couldn’t hurt.

Boy did it hurt sometimes. Early on, after my first MFA residency, there came a day when I hit a problem I hadn’t faced and didn’t understand—now I see it was dramatizing a particular event, bringing it to life, when I had some memories but some gaps and too few images. I experienced a little meltdown. Maybe I couldn’t write the book. I sent my wife a despairing email, which she wisely ignored. Then, later in the winter, I ran to my desk each day in eagerness to write another chapter, one about my father. So the average day during initial composition was pretty good. Fourteen months later, I emerged with a 500-page manuscript, which I set about paring to 300 pages.

The lessons continued as the years went on, post-MFA. The pains were trivial and passing compared with the joy of learning and of creating. And I now look back fondly on that clueless guy on the cusp of starting. More ignorant than egotistical, he didn’t know what he didn’t yet know. Before entering publishing he’d been a successful journalist and columnist who’d won awards for investigative series and depth profiles. The craft of writing, he reckoned, was pretty much a given. He couldn’t foresee the winding path ahead. The levels of the game.

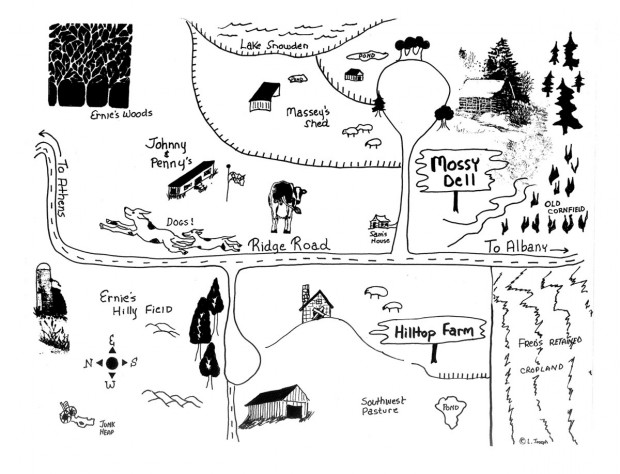

I recall that when he returned from his first MFA residency in late August 2005, having pressed his family into covering farm chores and having taken vacation time from the press to attend, he was chipper and in good voice. Sometimes I miss him. And I’ll say this for him, his intent was worthy. The book, a memoir, would be about how he, a guy who grew up in a suburban beach town in Florida, ended up operating a sheep farm in the Appalachian hill country of southern Ohio. It would be about his obsession with his charismatic, distant, farming father and about his father’s traumatic sale of their farm. It would reveal how he was even more scarred by something else—the effect of his grandfather’s suicide on his father—but couldn’t see that. It would depict the trauma he put his own family through as he tried to become a farmer himself: how he got into financial trouble, struggled with fatal and disgusting sheep ailments, and got seriously hurt trying to save a dying ewe. In the wake of his injury he had to sell his first farm and retreat to a neighboring property bought in his early lust for land. Finally he became a respected shepherd and supplier of breeding stock.

My story wasn’t quite so crystallized at the start, especially its emphasis on my father. What I really wanted to do—and this was my project’s worthy seed, I believe—was to try to explain, so someone else would understand, what it was like to win the farm of my boyhood dreams and then to lose it. That’s really what my literary ambition came down to. I yearned to tell about losing a magical farm so that someone else would understand, to fashion from my loss a beautiful song, a gift to the world.

Now, after seven-plus years of work on that book, I’ve just signed a contract to publish Shepherd: A Memoir with Michigan State University Press. The book is due a year from now, in Spring 2014. For me it’s a natural moment to reflect on what I learned. On what I still have to learn.

Learning the Craft

“I don’t think writers go to college,” my father informed me as I prepared to leave home for college. His unsparing honesty was one of the reasons I hadn’t revealed my ambitions, of course, but my dreams were obvious.

And while Dad was trying to be helpful, he was wrong. Not totally, in that his knowledge reflected what he knew of writers such as Jack London and Mark Twain and those of his generation—probably Hemingway and Faulkner. He didn’t know about Fitzgerald attending a prestigious Catholic prep school and then Princeton or about Dos Passos at Choate and then Harvard. Dad was a man of action. Though he’d graduated from a famous prep school himself, earning today’s equivalent of a fine college liberal arts education, he’d been thrown out of Cornell for landing an airplane on a campus lawn.

Afterward, he’d educated himself. He believed writing was about gaining experience in the world and then putting butt to chair. That’s how he’d written and self-published his own book, Success Without Soil: How to Grow Plants by Hydroponics

There’s some truth in my father’s vision of the writer, but it’s ignorant about the degree to which writers must be highly educated, through some process, by other writers. Hemingway, again, is the case in point, though he famously turned on all those who’d helped him.

“I think you can be big in this business,” my father told me as I, newly graduated, headed off for my first job. “But learn the craft.”

Today the writers are in colleges, and that’s where craft lessons usually start. I’m not building up here to say that an MFA is necessary, not at all. But education in craft by fellow writers is. For most, that tutelage continues long past one’s undergraduate years; the guild of writers schools its apprentices by means of chummy conferences, by stray remarks about their work, and by sharp blows to the snout—those cold, comment-less rejections.

Creative writing, in whatever genre, is an endless education, which ultimately does become self-directed, through reading books and from practice. But there’s nothing sadder than a man who sits down to write a big book, the book of his life, thinking it’s just a matter of butt to chair. I had been such a boy and almost was that man. And while I like to think I’d have gotten a draft done without my MFA program, I might have lost heart without its craft lessons and its affirmation. Because at Goucher College I gained an instant supportive community—students and mentors who live and breathe literature—and also began my long-overdue apprenticeship in the craft of book writing. I learned so much afterward, in writing draft after draft of my book—it’s true that the only way to learn to write a book is to write one—that I risk falling into the common trap of undervaluing my MFA as part of my process.

There are many paths, but the consistent key is learning, at first with help—with lots of help. I know a writer who published a fine memoir, with a big New York trade house, after taking post-college on-line classes (Stanford’s are great) and after attending writers’ conferences. (Then she got an MFA, desiring to write fiction and probably wanting the degree to teach.) After a while, reading deeply in your chosen genre is the main thing, and reading and raiding everything else, as you write. Plus all the other things you’ve always heard you should do and finally find yourself doing: looking up words, counting syllables, reading your work aloud.

So many times I thought of my father as the years went by: I’m learning the craft, Dad.

Emphasize Love Over Discipline.

“There’s a common notion that self-discipline is a freakish peculiarity of writers—that writers differ from other people by possessing enormous and equal portions of talent and willpower. They grit their powerful teeth and go into their little rooms. I think that’s a bad misunderstanding of what impels the writer. What impels the writer is a deep love for and respect for language, for literary forms, for books.”—Annie Dillard

Thankfully I came across this advice in The Writing Life early in my work; an MFA mentor had admired Dillard so I was reading her. Love, Dillard continues, is much stronger than discipline: only love gets a mother out of bed in the night to tend a crying baby. Discipline has its place—after a writer has gotten in shape, built his muscles. After he’s made himself ready, in other words. You don’t set out to run a marathon on your first day jogging,

I used to wonder why it took writers so long to finish a book. I didn’t realize they were producing multiple versions of that book. Mine took six complete versions over seven years, with each sentence, paragraph, passage, and chapter worked over so many times I lost count. While part of me can’t believe it took seven years, using Dillard’s figures in The Writing Life the average length of time is six years to produce a publishable manuscript.

Honestly, I thought my fourth draft would kill me. I had to force myself to the keyboard each morning. (More about that draft below.) Then the usual happened: it took an hour to re-enter the work, and in this case to overcome my resistance born of fear of failure as well; in the next hour I started producing; in the third and final hour, all I’m good for, came the good stuff. My usual hourly rate held steady, a page an hour.

When I was a journalist, an author of many books said to me during an interview, “It’s not that I’m talented or hard working, but I can sit there hour after hour. A lot of people can’t do it. They’re smart and talented but just can’t.” I learned to my relief that I could do that, sit there. In the first year I worked five days a week, and then increased that to six, and in the final years usually worked seven. Luckily, I like making sentences. And after a year and a half of writing for hours daily I noticed that my sentences seemed better somehow. They felt more fluent, and I’d learned the secret of varying their structure for rhythm, musicality.

In the end, the self that apprehends meanings, the part of us that would say this is true, is all-important. While it is difficult to face the blank page day after day with the self, much of that grandiose problem seems simply the difficulty of thinking: writing is concentrated thought. Yet it’s true as well that one writes in Kierkegaardian “fear and trembling.” You’re trying to make something out of nothing. One wants—no, wishes—to be worthy. All one can do is put one’s head down and try, hope that the work itself will call forth—and in some way help supply—any necessary personal transformations. One must begin humbly but bravely wherever one is. And try.

But ideally not try so hard that you lose the fun and let fear win. Because that’s what “lack of discipline” usually amounts to, fear and confusion. Maybe it’s all confusion, because ignorance creates fear that can only be remedied in the practice itself and through education, both willful and accidental.

No wonder Bill Roorbach counts birdwatching and gardening as writing. Writing is fed by what lies beneath the straining ego; I think of that vastly larger continent as—there’s no better word for it—soul. Or, if your prefer, Jung’s collective unconscious.

Don’t Submit too Early

If you think your book is ready for publication, it isn’t. You must know it’s ready.

A rookie mistake, which also afflicts writers at every level, is sending off a manuscript too early. It’s hard to see your own work, but I can now see my un-admitted doubts when I began to submit my third draft. I’ve read that Philip Roth sent his novel drafts to five people, and I like to imagine who they were: three wickedly good fellow novelists, a sensible and erudite lay reader, and, what the heck, a Rabbi. Don’t we all hunger for absolution?

Okay, maybe just me. But everyone needs a writing posse. At some point, however, your chief deputies can fail you if they too have read the work, or its pieces, so long that they’re blind to its faults. Plus, they want its and your success. I was fortunate that an editor, in a roundabout way, kindly directed me (actually he was none too kind, but accurate, in calling my book “plodding”) to obtain the services of a developmental editor. So I found one. Namely Bill Roorbach.

Development? That isn’t a big enough word for what Bill did to my book. I mean for my book. From sentences to story arc, he laid about with a heavy sword. But with a strangely positive energy and kindness—he believed in my story! All the same, when I got his report I crashed for three months. My persona wasn’t working—there was blurring between me then, the guy in the action, and me now, at the desk recalling (plus he mentioned a meta-level of me beyond all that: the me creating the me at the desk; that one still tests the limit of my cognitive abilities). The narrative arc wasn’t working because I’d bring up a key element, my hired hand, say, and dispose of him right away, as if the chapter were a stand-alone essay. And my scenes were not sustained enough to fully dramatize my experience.

Whew. Bill’s markup in Word looked like the Fourth of July. I say I crashed for three months, but the actual fetal position surely lasted only about three weeks. Then I got up and sat and thought, and walked and thought, and read voraciously. I questioned myself down to the soles of my feet. I grasped what Dillard said about sitting with a book as with a dying friend. I decided I’d worked too long and hard to quit and let my book fully expire. Though I’d cobbled together an awkward narrative homunculus, I still yearned share the loss of my farm. And my monster’s heart was there, weakly beating. Bill said the creature just needed major surgery.

So I began writing a new version that truly was new, the fourth draft, and about a year later I had it, another baby whale, the manuscript having grown again to 500 pages. Eventually I cut it to a svelte 360, and broke up that chapter on my father and dispersed him throughout the book. Where he should have been all along—as an MFA mentor had mentioned the better part of a decade before. I went through the book a couple more times, smoothing sentences, looking at persona, and clarifying timeline.

Finally I knew my memoir was ready, and thankfully hadn’t burned too many bridges with my early efforts. Because that’s the problem with submitting a book before it’s ready, not just initial rejection but permanent rejection. It’s natural for neophytes to think, This may need some work, but they’ll see it’s a diamond in the rough. They’ll want to work with me. Nope. Not unless you are Bill Roorbach or Dave Gessner. There are too many other manuscripts that are ready, clamoring for editors’ and publishers’ attentions. They cross you off and move on.

Now, bearing a book contract, here I am, this putative font of wisdom who’s really just trying to advise himself. Trying to codify what I fear I’ll forget. Because I sense levels to this game I can’t articulate. I have questions none but a fellow writer can even understand. I wonder, for instance, how one manages his own nature in order to write a particular book. Which you, and how cultivated and cajoled, will it take to express something wholly new and even at odds with the person who wrote the last book? Not to mention his three personas.

My twentysomething son says my writing would be so much better if only I’d reveal how weird I am. He’s the one who caught me laughing, during ignorance-is-bliss draft one, at something I’d just written. And the kid’s got a point—maybe for my next book. Will it be a novel? Might I gin up a plot and use my weirdness to animate half a dozen characters? Or will I, poet- and purist nonfictionist-like, hoard my weirdness and other gifts and pains solely for my lone creative-nonfiction-prose purpose?

Time will tell. One thing’s for sure. I’d better ratchet down my advice until I’ve produced another book. Then, watch out. But don’t hold your breath, either, because I am one slow learner.

Richard Gilbert teaches writing at Otterbein University. His short memoirs have been published by Brevity, Chautauqua, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, and other journals. His essays and articles on gardening and farming have appeared in Sheep Canada, Stockman Grassfarmer, Farming: People, Land, Community, The Shepherd, and Orion. For five years he’s written about storytelling at his blog, Narrative, which he’s renaming Draft No. 4 for obvious reasons. http://richardgilbert.me/

Richard, This is a fabulous piece. I plan to share it with my students. As a fellow graduate of Goucher’s MFA still struggling to complete a publishable manuscript, I appreciate all your advice, as well as your father’s. One lesson I’ve learned is that the longer you wait, the harder it is on the lower back and hips to sit for those three hours/ day. You were fortunate to find a good mentor and smart enough to take his advice. Three months is not a long time to be crushed. Believe me. I keep quoting to myself a line from The Tortoise and the Hare: Slow and steady wins the race. Hope it’s true.

All best, Judy, Class of 2001

Great to hear from you, Judy. Your comment makes me realize my TRUE first lesson: get a good chari! I’m serious. I have back issues but started by sitting on a plain wooden dining room chair. After a few months, my back just kind of broke down, went out, very painful. My wife and I went out and got me a good one. In later years we moved and I’ve written all over the house, most of it reclining in a La-Z-Boy.

I also tell myself, You’ve got to love the process, because it’s all process. I think of all the late-blooming middle-aged and elderly painters out there. They are artists! Many are talented and some are gifted. Never gonna get famous or probably even close to whatever the equivalent is to being published. I admit I wanted it, but the project and its process should be more important than that. To a degree, I think, art for art’s sake. It takes almost everyone so long, why make this profound activity dependent on others. While of course trying to reach and please others. A paradox.

Thanks for this – a wealth of information and experience! I’ll reread this a few times to grasp what you’ve shared, see how I can apply it to my work in progress. Off and on for 14 years of research and information-wrangling, some big gaps where life got in the way… frustrating to me until I (finally) figured out that I needed the time away to gain emotional distance from my interview subjects. The Annie Dillard quote about love trumping self-discipline serves as that approval-seeking you mention.

Congrats for persevering and for listening to those who who could help.

Thanks, Martha. Best wishes in your work!

This is a fantastic post. I’m in the middle of this story, an award-winning journalist wrapping up a low-res MFA program (VCFA) in which I started a memoir-in-progress over from the beginning and has now become a different, more personal, and I believe more literary story. Yes, I sent things out before I should have; as a nonfiction writer I knew you could secure contracts when the book wasn’t written; now there are some publishers my agent likely can’t go back to when I am actually done because they already said no to something that wasn’t ready. And yes, it is about writing multiple versions of the same book. I now have version two complete, and this month I’ll start going through it, culling, connecting, weaving, polishing, hacking, whatever it takes, for however long it takes. Thank you for helping put my path in perspective.

I appreciate the endorsement, Patrick. And hang in there. I found that my own writing background was equal parts a help and a hindrance, or maybe just meaningless, in writing something so different, a memoir. Persona is so much more important, for one thing.

Congratulations, Richard! This is a wonderful accomplishment. Thought of your literary interests recently when Tom and I went to see Lincoln. Hi to the fam.

Hi, Karen! So nice to hear from you in this way. You’d sure know the landscape I mention.

Sometimes a posting here comes exactly when I need it–like this one. Thanks!

Great news. I loved reading this post.

Thanks so much, Steve. I enjoyed writing it, felt like clearing the decks.

I loved this! In a twisted sort of way, I would much rather hear about how hard someone’s book-writing experience was than how easy it was – it makes it seem more doable somehow. Thanks for giving a peek into your process.

You are most welcome, Louise, and thanks for your comment. But, hey, there’s a lot of bragging between the lines of this too, you know. I did make every mistake in the book, and think I invented two new ones, but persevered because I believed so strongly in my story. That alone is not enough. Not for publication. Hence the suffering!

Congratulations Richard. I look forward to reading your new book. Doug

Thanks so much, Doug—me too! I wonder if I will like the narrator? He sure put me through hell. Though which persona is guilty, per Bill Roorbach’s analysis, it’s hard to say. Actually, all three of the bastards did: me then, me at the desk, me above the desk . . .

Congratulations, Richard! I can’t wait to read it.

Thanks, Tim! I sure enjoyed your memoir.

This blog gets better and better. I love the guest posts. (But I still love Bill and Dave!)

You should write one for us.