Guest contributor: Jim Lang

Bad Advice Wednesday: On Getting It All Wrong

categories: Cocktail Hour

2 comments

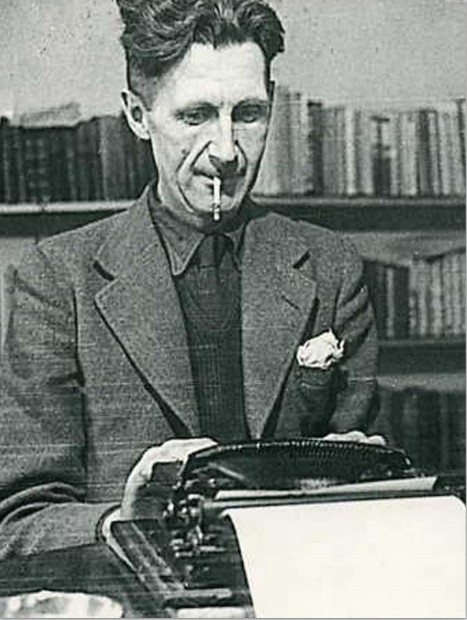

I re-discovered George Orwell in a Paris bookstore in July of 2013. I was scanning a case of books about Paris, hoping to find a title that would help me better savor the pleasures of the city, when I spotted a forlorn copy of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London on the bottom shelf, eclipsed by the glitzier travel offerings. I brought it back to my hotel and started it that afternoon.

I re-discovered George Orwell in a Paris bookstore in July of 2013. I was scanning a case of books about Paris, hoping to find a title that would help me better savor the pleasures of the city, when I spotted a forlorn copy of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London on the bottom shelf, eclipsed by the glitzier travel offerings. I brought it back to my hotel and started it that afternoon.

As I read Orwell’s nonfiction account of living and working among the lower classes in two of Europe’s capitals—washing dishes in the basement of a swanky Parisian hotel, sleeping with the homeless in Trafalgar Square, picking hops with migrant workers in the London suburbs—I was astonished at how beautifully and insightfully he captured the lives and conditions of the poor and marginalized members of his time. His analysis of poverty, its causes and effects, struck me as deeply relevant for today, since Orwell was writing at a time of swelling industrialization and an increasingly globalized economy.

Down and Out sent me into Orwell’s other writings about the poor and oppressed classes of his time. He chronicled the horrific working conditions of miners in the north of England in The Road to Wigan Pier; he gave an account of sleeping in homeless shelters in “The Spike”; he depicted the oppressed peoples of the British empire in “Shooting an Elephant” and “A Hanging.” I found all of these analyses equally penetrating and eloquent.

What a prophet, I thought to myself! Everyone knows that Orwell accurately prophesied things like the rise of the police state, the failures of communism, and the denigration of the English language; but it seemed to me that the world had yet to see his equally brilliant analyses of poverty. I became totally convinced that, eighty years after he wrote them, his arguments on this topic deserved a fresh airing. I envisioned a book project in which I would present the world with Orwell’s trenchant analysis of poverty in a capitalist society, and highlight how vital his work remained for us. My tone would be reverent—I would be a humble acolyte broadcasting the genius of the master.

So I dug into Orwell more deeply. I read his early, mostly forgotten novels (ever hear of The Clergyman’s Daughter or Keep the Aspidistra Flying?); I ploughed my way through a four-volume collection of his essays and journalism; I read several book-length volumes of his letters.

And did so with an increasingly sinking feeling.

While I continued to find powerful insights into poverty, and especially the debilitating effects it has on those who suffer in its grasp, I began to see that the prophet Orwell made many predictions that have turned out to be dead wrong. Worse still, he usually made them publicly and quite confidently.

Many of his ill-made prophesies stemmed from his conviction that World War II would destroy Christianity and capitalism. So here, in an essay on the novels of Henry Miller called “Inside the Whale”:

“What is quite obviously happening, war or no war, is the break-up of laissez-faire capitalism and of the liberal-Christian culture . . . Almost certainly we are moving into an age of totalitarian dictatorships—an age in which freedom of thought will be at first a deadly sin and later on a meaningless distraction.”

One sees here glimmers that will result in the storyline of 1984—but not the storyline that would play out in the real world. Still, while Orwell feared the rise of the totalitarian state, he was quite happy with one positive result he foresaw from the death of capitalism. Separate economic classes, he predicted, would disappear:

“This war, unless we are defeated, will wipe out most of the existing class privileges.”

Ahem.

Orwell wasn’t just wrong about the big economic issues of the day. For several years he wrote a weekly newspaper column called “As I Please,” and one of those columns takes up the pressing question of whether or not humans will ever be freed from the drudgery of washing dishes. Orwell envisions that the eventual solution will be communal dishwashing:

“Every morning the municipal van will stop at your door and carry off a box of dirty crocks, handing you a box of clean ones (marked with your initial, of course) in return.”

Mistaken predictions like these can be found all through his published and unpublished essays, on topics large and small. But one of the reasons I love Orwell was that he was his own best critic. Writing while the war was winding down, he looked back at his own work and noted how wrong he usually was:

“One way of feeling infallible is not to keep a diary. Looking back through the diary I kept in 1940 and 1941 I find that I was usually wrong when it was possible to be wrong.”

So Orwell was not quite the infallible prophet that I had first imagined I had found. Part of that may stem from the fact that he was such a prolific writer—his collected writings total more than 8,000 pages—who frequently engaged with political topics in magazines and newspapers. But part of it stems from the fact that he was a human, and humans aren’t perfect.

Once my initial disappointment at Orwell’s humanity wore off, and I continued to dig my way through his collected works, I could see how much valuable insight still remained from his early nonfiction writings, and a new way to think and write about Orwell, and his continued relevance for us, began to take shape in my mind. I’m still writing the book, even if it won’t quite be the one I first envisioned.

But reading his collected works, and seeing how often he got it wrong, has changed my relationship with Orwell. I no longer see him as an untouchable genius, as the author who produced masterpieces of political prophecy, and who perches atop his literary throne above the rabble of the rest of us.

Nope, Orwell was a writer who sometimes got it wrong—among his other faults. He also liked to make fun of people he referred to as “sandal-wearing vegetarians” or “fruit-juice drinkers.” And he made occasionally baffling remarks like “you can only love your enemies if you are willing to kill them in certain circumstances.” Some of his essays have really terrible endings. His early novels are mediocre at best—a fact which he also recognized, requesting that one of them never be reprinted.

As a writer myself, this was all quite liberating to discover. Orwell was a writer, and he did all the things that the rest of us do: struggle with words every day, write occasional bad sentences, get things wrong, haggle with editors and publishers, plead with his agent for better deals, and churn out essays when he didn’t have much to say. He did, in other words, the same stuff that I do.

So for my bad advice this Wednesday, I recommend that you read some really terrible shit by your favorite canonical author. Get a collection of their letters, their early essays, or that first or last novel that nobody reads. Read James Joyce’s poetry, or David Mamet’s political screeds. When your heroes have been knocked off your pedestal, you might find that hanging around with them becomes more enjoyable. They’re not perfect, and neither are you.

But don’t let that stop you from writing—Orwell never did.

James M. Lang is the author of four books, the most recent of which is Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty, published last fall by Harvard University Press. His current book project focuses on George Orwell’s nonfiction writing about poverty. Visit his website at http://www.jamesmlang.com or follow him on Twitter at @LangOnCourse.

I really enjoyed this piece. As someone who frequently spouts off about things large and small and often gets them wrong, I found it comforting. The dish-washing prediction was funny, too, though considering we ship raw materials from here to China and finished products back here in big metal containers, the idea of transporting crockery to be washed isn’t really so far fetched:)

Hi James. Well I started to read this piece when it first aired BUT I was in my first throes of writing a new essay that included a moment in Paris THEREFORE I had to abandon you since I didn’t want my thoughts to absorb someone else’s Paris. Now that I’ve returned to your piece I wanted to say, IT’S GREAT.

Yes, it’s really true that we start to allow people we trust or admire to become the voice of greatness and righteousness and that’s just lazy and dangerous–especially when we are speaking of politics. But personal choice too. And artistic choice. Oh, this all leads me back to the word responsibility…I hate it when that happens.