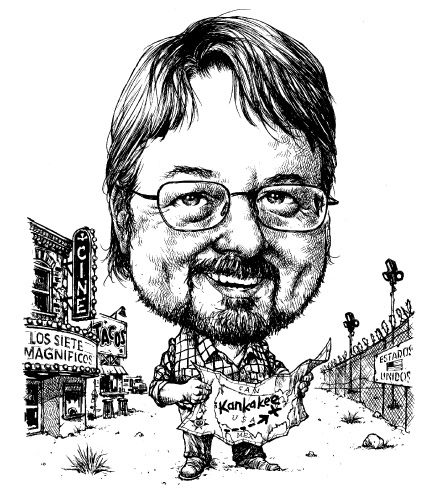

Guest contributor: Luis Urrea

Bad Advice Wednesday: Get Me To the World on Time (Six Thoughts on Place in Writing)

categories: Bad Advice / Cocktail Hour

5 comments

Bill and Dave are thrilled and honored to have the prolific and brilliant Luis Alberto Urrea doling out today’s advice. This talk was originally delivered at the Tin House writer’s conference in Portland, July 2013.

Bill and Dave are thrilled and honored to have the prolific and brilliant Luis Alberto Urrea doling out today’s advice. This talk was originally delivered at the Tin House writer’s conference in Portland, July 2013.

Take it away, Luis:

Here’s what I’ve been thinking: In the real world, we can only visit Place, but in the alchemy of writing, we become Place, and Place becomes us.

I–My First Thought.

I am here to discuss Place in writing. I imagine you are expecting to hear about form and function, critical choices and possible pedagogical formulations to further your theorems about the primacy of Place in modern literature. Well, didn’t Aristotle say that Place is that part of space where you are what is? If he didn’t, he should have.

At its basest level, Place is imagery. Setting. Or, God help us, it is metaphor. Thus do hacks torture us, making the world into bad greeting cards. For a masterful version of Place-as-more-than-setting, see Eudora Welty’s “A Worn Path.” I defy anyone to use landscape and weather and color and sound any better.

For an equally masterful use of Place-as-metaphor, only this time craptastic and besmirched, see the latest colorful TV ad for the mega-three-pound-bacon-nacho-killerburger. In it, you might see cute blonde toddlers frolicking in a field with baby ducks and a puppy, while a manly singer bellows: “Bacon! Gotta have it!” The field is golden, by God. And behind it, the mountains are indeed purple and majestic. The sky is a blue yonder free of pollution, chemtrails, or climate-change mega-funnel clouds.

The advertisers are not promising to grind children and cute animals into their diseased beef patties. No. They are, however, cynically using your love for sentimental landscapes to make you certain, on a cellular level, that gobbling thirty grams of blubber will make you a healthy, happy, patriotic and eternally sinless American.

Place is more than that, of course.

If you’re interested in using Place in your work, try this: stop using it. Try inhabiting it. Your story and its characters need a good hard surface to walk on. You can’t walk on fog. Nobody ever ate a metaphor or built a house on one or made love under one. Once you walk it, you won’t mistake London for Beverly Hills, or the desert for the mall. Make it real. Let it be real.

Imagine how hard it would be to take poor Heathcliff and Cathy seriously in Malibu. Your soul is my own, and your boogie board is bitchen. Dude.

#

How do we get there?

Start with your butt: that small seat you’re in is the world right now. Or Reed College all around that seat. Or the Tin House writers conference. Or awesome Portland. Or my favorite western place, Oregon: the placiest place around. That seat is where you are what is, right now, at the center.

That seat is sacred right now because your body is in it. This building is sacred right now because your seat which holds your body is in it. Tin House and Portland and Oregon and the American west…sacred. Better yet, deep inside this expanse, inside that body, are you. You’re in there. I’m waving at you.

Hi, friend.

This is the place, opening around you to expanding layers of light, like Russian nesting dolls.

If you want to discover this nesting-doll quality of true Place in writing, go find Virginia Woolf’s “Kew Gardens.” Box after box opens, taking us deeper and deeper into the garden until we come down to regard a small snail inside his own boxy shell inside the box of the garden inside the box of the city. It’s like flying from the highest part of the atmosphere–ironically, the world opens to us more and more the tighter our focus gets. That garden is the world and more. After you’re done with Woolf, see Steinbeck’s story, “The Chrysanthemums.” Lids coming off boiling pots, then slammed shut again in the most heart-breaking way. We fly up and out of the story as the world shuts down.

Place in writing is not created with adjectives and adverbs. Those are butterflies flitting around. Place is made of noun and verb. Rock, not ideas. Place smells–sometimes it stinks. It has a sound–sometimes it’s silence. It has flavor–high mountain air to me tastes a little like sugar. Place is specific. Even the sky is specific.

If you turn your ankle on a rock, you know Place can be very small yet vivid as hell–ask Cheryl Strayed.

#

For our purposes here, there is one commandment: you, as Place, must be a shame-free zone.

I repeat: a shame-free zone.

You are as glorious as the great volcanoes on our horizon, as the mightiest rivers pulsing across the northwest. You cannot be too thin here, too fat, not muscular enough, not beautiful, not healthy, not strong, not daring, not correct, not busty enough, not the right party or color or gender or sexuality or ability. For you are the ground and the crown of creation right here, right now. You. Are. Here.

You are the place. And you are made of stories. And so is the place all around you.

Here’s a writing prompt: go rub some dirt on your face.

#

II–My Second Thought.

I am a Place-harlot. It’s true. I’m easy, and I’ll make love to any place I find. It’s embarrassing, and I sometimes think I should get therapy. My kids dread our many jaunts into the world because I am scarfing up real estate magazines and sweating over them like porn. I’m going to live here! I announce it several times a year. Fortunately for us as writers, we can and do live everywhere we love (or hate), and can move there whenever we open our notebooks. Or escape from it.

Most recently, I have decided to have an orgy with Cartagena, Colombia followed by some jello-wrestling with the island of Curacao. I wanted some serious naked hot tub time with San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Well, I did do that with my wife on a rooftop staring at the lit cathedral spires, so– Score!

However, I have also recently decided to live in most of Montana. Cindy and I spent three days living forever in Leavenworth, WA last week. And I will always live out beyond Joseph, in the Wallowas. You might actually find me out there one day, playing out my last years in a cabin. Come on over–we’ll have coffee.

It has often been said that a major feature of Western Literature is the use of Place as a character in the texts. I first read this about Edward Abbey, but you can find such comments about Stegner and Terry Tempest Williams and James Welch and Larry McMurtry and Bloody Cormac and Leslie Marmon Silko and Bill Kittredge and my teacher, Linda Hogan. Place is the gleam behind Thomas McGuane’s most magnificent prose.

Places are people, too.

Just ask the haiku masters and the medicine people.

For example, Basho recommended: “Learn about pines from the pines, and about bamboo from bamboo.”

He also said, “Make the universe your companion, always bearing in mind the true nature of things–mountains and rivers, trees and grasses, and humanity–and enjoy the falling blossoms and the scattering leaves.”

Did you catch that? Universe, mountains, rivers, trees, grasses. Humans. There are those old nesting boxes again. And there we are, in the list of places. But the old monk put us last, after grass! Keeping us humble, something place tries to teach us every time the sun comes up.

Onitsura, funkier than Basho, said:

“To truly know the plums

Own your own heart.

And own your own nose.”

#

III–My Third Thought.

Do you want to meet a great character in a novel? Visit the Overlook Hotel in Stephen King’s The Shining.

I love Place because that’s where the ghosts live.

However, I sometimes doubt the very concept of Place because for humans, I believe the essence of it all is story. We don’t even live in a place: we live in the story we tell ourselves about the location and the land and the far horizon. This is all a story being told to endless night.

I grew up poor and worried in San Diego, California. You couldn’t have placed me in a more heinous and shit-caked glob of slag if you’d consorted with Satan’s housing department.

“Get me to the world on time,” the title of this little essay, was a song by The Electric Prunes. I was an insomniac, set afire every night by the terror of poverty and despair and the nightmare of my family’s implosions. I listened to rock and roll till two or three a.m., then stepped into our sad back yard, where a mother skunk would bring her kits. We had worked out a pretty good deal–she’d threaten to spray me, but wouldn’t. And I’d walk around in my underpants with her family and write poems about her.

The skunks and the night were a ritual that made that space sacred. And the hours sitting on the floor of that bedroom with my notebooks and music made that space within the larger skunk-blessed yard sacred as well. I did not know that this was a journey that made the place within me sacred too. And I walked many miles inside myself on those nights.

That place appears in its ten thousand faces in all my writing.

Me and the skunks and the Electric Prunes.

Imagine my shock when, later, I found out the stories people told themselves about San Diego were stories of sunlight, blue seas, warmth, joy, freedom. Was this really the place? It was.

It was both. And once I earned a penny or two, by gum–I liked the hell out of their story and it became a sunnier place that I visit as much as I can.

#

IV–My Fourth Thought.

This piece is being written by the Wallowa mountains of eastern Oregon. Also, the town of Joseph out beyond Hell’s Canyon in Eastern Oregon. It is being dictated by the rushing river outside our back door. And whatever beauty and haunting to be found in it is being dictated by the great lake lapping near the foot of Old Chief Joseph’s grave.

I have been teaching writing here with Kim Stafford and others since 1997. But this summer, I am hiding out, working on my own writing. And the place is teaching me.

Across the river from our cabin is that damned Benjamin Percy. With that damned voice. I told my kids, “Ben’s the werewolf of the family.” It was great here till the Percy clan arrived. Their kids start howling in a blood-curdling chorus when the moon comes out. Ben murmured in my ear, “Keep your windows locked.” Jen Percy and I talk about demons. Fun times.

It’s the light here. The light is home, the way it goes green from the trees. And the deer stand at the foot of the back deck stairs looking up at us and hoping somebody will drop Cheerios. The story grows rich with the pile of bear scat between us and the river.

Fifteen years ago, it was country wives and potato farmers. I was nobody. I still am nobody, except people have been convinced otherwise by videos and newspaper stories. Now, people truck the many hours from Seattle and Portland and Boise and northern Utah to write. I’m hiding out for once, not teaching, enjoying invisibility.

Our children grew up here. Our youngest learned to crawl here. The first thing she did upon rising to hands and knees, was to back out of the cabin and commence to screaming when she realized she was all alone. She learned to ride horses here. And to drive go-karts here. And last summer, she learned how to write poetry here. I’m not sure our kids have yet learned to sit by the river and hear all about the appaloosa horses that were bred here, or the struggles of Chief Joseph and the People, or of the water’s long tumble from the snowpack to the burly channel rushing past, or the many stories of the fish trying to outsmart the fellows with poles and hooks and beer. But Place is teaching them.

The little one is no longer little and back this year to learn more poetry–a couple of sessions ago, the bear snuck down the mountain and stole her workshop’s M&M’s. Imagine the story he told when he got back upslope. He and Bigfoot are workshopping haiku now:

“Crunchy sugar berries

every color with dark centers

give me diarrhea.”

Be here long enough, truly enough, and you will be here again in a Chicago winter, trapped in brown snow and jammed traffic in the smoke from the I-290 smelters. The stories the rushing river keeps repeating will suddenly make sense in a rain storm when the Illinois drought breaks and the tornado sirens are about to send you to your basement. There is a rushing river in my spine. There is an appaloosa behind my ribs. I have drunk the water and it has formed a small lake inside me, where the fishes move silver and pink, slowly waving their great tails. If there weren’t, would I write?

I have always been here, the river says.

You will always be here.

#

V–My Fifth Thought.

I mentioned medicine people. And ghosts. I have seen ghosts, and I have been touched by ghosts. So I’m a little goofy in this part. But bear with me.

If story is Place, and stories are ghosts, and we are also Place, full of story, made of story, surrounded by story, making story–then writers are haunted houses.

How can you ever have writers block when there are spirits cavorting in your rafters? And when there are aspens and junk yards and glaciers (albeit evaporating) and swimming holes and Sears Towers and abandoned playgrounds all around you? Inside you.

Trust a place and it will bring you stories.

Once, when I was struggling on my 26 year hike through the writing of The Hummingbird’s Daughter and Queen of America, I was lucky enough to live in Boulder, Colorado. Yes, I was Colorado’s harlot-man. I lay on her sunny slopes and grunted up and down her mountains and ate her wild apples off trailside trees. I ate lunch in the middle of elk herds and I gossiped with marmots. You will find her aspens everywhere in my words: the sunlight bouncing off aspen leaves like a dance party of mirrors taught me how I wanted to write. I should dedicate every book that came after 1995 to one tree.

Basho would be laughing right now: college degrees? A million craft lectures? Screw that. One breeze and one aspen taught me more. The mountains behind it helped.

So one of my teachers (not professor–big difference) was Vine DeLoria, Jr. You might know of Vine. He was an Oglala Lakota thinker and author–wrote the classics, God is Red and Custer Died for Your Sins. He was a cranky man. But he knew how to laugh. Oh, yes. He knew Place.

We were standing outside one day, staring up at the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. These Rockies are the baby Rockies–the real monsters that rose a mile or more before the Rockies we know now were so ancient they already rose and fell to pebbles. Did I mention story? When you know the story, you see ghost mountains. Storm clouds over the Divide tell you the story of the ancient mother mountains–they rise as hauntings, echoes of the vista. A mirage.

Basho would tell you mountains have ghosts, too.

Because like you and me, mountains are also dying.

Have mercy, they cry in church. Yes, have mercy. When you honor the place where you stand and dream, you have mercy for every transient thing–grandmother, child, aspen, mountain, marmot, poet.

So Vine said, “What’s your problem writing this book?”

“It’s an indigenous story,” said I.

“So?”

“Well, I don’t get it.”

“What’s there to get?”

“Like,” I said, “the spirits. Right? You guys have these spirits all over the place. I’m not sure I get it.”

“Spirits,” he said. He was as always smoking, but this time it seemed like the smoke was from the irritation burning inside him. We were near my writing-teacher aspen. It was sparkling. “You know,” he announced, “when you Christians still had faith, you had a holy book. Haven’t you ever read your own book? In it, it says that everything in creation is given its angel. Its guardian. My God, man, read your own book! Our spirits are the angels of place.”

I probably said something like: Uhhh….

He pointed at the baby Rockies with his cigarette. “These peaks are alive with angels. But they are lonesome. Do you know why these peaks are lonesome? Because these spirits speak Arapaho. They don’t speak the language of the invaders. The Front Range does not speak English. And nobody has spoken Arapaho to them in a century. Go up there,” he said. “Learn to speak Arapaho. And sing to the mountain. I promise you, you will receive a miracle.”

The rest is between the Rockies and me–but I never forget the place, and the place does not forget me.

#

VI–My Last Thought.

Everybody knows what Mary Oliver said. But I’m not sure everybody thinks about it. She said:

There is only one question:

how to love this world.

OK, Shaman-Boy, you’re probably thinking: how does this help me when I’m facing my frigging lap-top?

Well, start again with your butt. I am very fond of your butt: it’s so real. No pretense. Be there. Because you are the place inside Place, and the largest place is inside you. And there you sit, holy.

We are afflicted with MIND. We are so busy being intellectual and brilliant and firing off our lasers and whisking up yummy merengues of incendiary language that we forget that we don’t write with our brains. Not completely. Unless we are trying to impress those desiccated vampires on PhD committees. We work with our bodies. We work with our hands. We are perhaps carpenters. But we are surely gardeners. We have our fingers in the dirt and the muck. That crap that befalls you, in whatever Place you wish to escape from, goes into the mulch pile and turns rich and black and moist and you pile that on your sprouting seedlings, baby.

That crazy homeboy Chekhov pointed out that to chemists, dung and roses are equally valuable to a landscape. Writers must be the same.

Work with your hands and your feet and your bootay.

Place–landscape, for example–can dictate two thirds of your story if you let it. If you trust it. If you honor it and tell the truth about it. Place won’t forgive your lies. It will probably grow some nice vines over your errors until they soften and blend in. Insults? Watch out, man. Place can be a real bastard.

Our venerable Tin House main man Rob Spillman never tells a lie. But he was recently in Chicago and dissed the crap out of it in a tweet. Then Chicago, all offended, summoned tornadoes to stop his train mid-track. TAKE THAT! Chicago said. I think it was a draw.

#

Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian could not have happened in Vermont. “That loathsome cadre beswarmed the earth from another realm entire, slouched upon its hellion horses bedraped with the reeking pelts of their huddled victims, until The Judge–his necklace of human ears and teeth rattling in the tubercular sunlight–reined in and desaddled at the shadowy door of Ben and Jerry’s.”

Kim Stafford speaks of “eloquent listening” as a path to good writing. I tried to take a page from him and surrendered to eloquent looking.

Look. Just, look. But look like you’re on fire and seeing is water. Pay attention. This is sacred work.

Not religious work. Don’t worry, atheist amigos. I’m not talking about religion. That’s a different lecture, and one I am dying to give. After all, religion as a word comes from the same Latin root as ligatures. To be tied down. Pretty specific. Pretty physical.

The good news is that Place has such nice sharp edges it cuts through ropes and sets you loose so you can get to the work of true praise.

#

One last story about Place.

My friend “Sonny” is a Pima warrior who has lived some hard times. He is well known in Oregon, so I have changed his name, because he is suspicious of people crowding into his story. Vine introduced us.

He lives in a teepee in wilderness between Northern California and Oregon. Firmly rooted in Place, and this is the place from which his thought grows. He knows the night sky and he knows the woods and he knows Bigfoot. Yep. He can sit all night watching the Milky Way. I think he can. I went to bed after about six hours.

Sonny is a university-trained restoration ecologist. He goes into his beloved Place and works to heal the story that has been imposed upon it by some ham-handed late-comers who have destroyed the sacred text of the land. Clear-cuts and pollution fill Sonny’s work-days. He is the only scientist I know who uses both the lab and the Good Red Road in his work.

I once saw him embracing a giant cottonwood, whispering to it.

“Tree hugger!” I joked.

He said, “He’s 150 years old. What’s wrong with hugging someone you love?”

In his wilderness, there is a tribe whose land has been ravaged by the newcomers. But the tribe is scattered from its birthplace, and only two or three old-timers remember the tribe’s words. Most have been forgotten. English is the new story.

Sonny did the following, before restoring the land: he brought tribe members back to Place. He reinstated the ancient tradition of the morning gathering, where members spoke communally of their dreams. He brought the elders and facilitators in to teach the young the few original words still extant. And at night, they dreamed. And slowly, each morning, the names returned. People dreamed the names of the plants in the mother tongue. And Sonny kept a chronicle.

As the dream-words came back, the songs returned. And the prayers. And rituals returned as the place awakened. Words became flesh and dances returned.

Only then, only after Sonny had the glossary written out, did he begin to restore the banks of the creeks. Planting the right bushes with their real names. And the trees with their names. And he has never told anyone outside this tribe what the words are. And the waters cleared, and the trout and salmon and steelhead returned.

Words are landscape.

That’s the best I can offer you about Place.

Speak the right words, and the dragonflies and otters and aspens will return.

It can be terrifying, as I learned writing The Devil’s Highway. It can be transforming, like our little outdoor amphitheater here at Tin House. But it must be yours. Completely. In making it yours, you make yourself part of it. Even the most slipshod reader will know if you don’t. Only you can whisper your Place’s true names. If it is utterly viscerally yours– then it can also be min

And I thank you.

Rumi said:

“Let the beauty we love be what we do.

There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.”

A 10th anniversary edition of Luiss Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway, is coming out this year, and Ecotone was lucky enough to publish the new Afterword.

(Please take a second to “Like” Bill and Dave’s up there in the upper right hand corner. We are both kind of needy. “Like” this post, too, upper right.)

I cried in several places reading this. I don’t have words for how moved, and encouraged, I am. But I will say, despite being from Chicagoland, and currently living in Maryland, I have a special relationship with the Sandia Mountains in New Mexico. Lovely to find someone else I can say that to who understands.

“Trust a place and it will bring you stories.” Oh, yes.

Thanks, Luis–This is beautiful. Great to have you in our place, even better when we can gather someplace real. Till then, my friend!

Refreshing, that’s what your words are, and encouraging and playful. Thank you for this article. I like the way you think…and consequently write.

I can’t “like” because I don’t have a FB account. But if I could, I certainly would. For all of you.

This piece is balm, indeed. Thank you, Mr. Urrea.