Table for Two: Interview with Wes McNair

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

2 comments

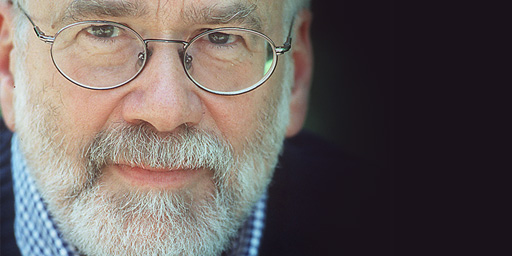

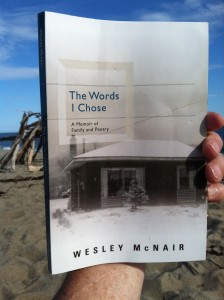

This coming Thursday, January 31, Wesley McNair will launch his new memoir, The Words I Chose: A Memoir of Poetry and Family, at the Portland Public Library in Portland, Maine, always a good venue for writers, now a great one in its new renovation. And a brilliant evening is planned. It wasn’t hard to imagine where Wes and I would sit for our pretend meal–the porch of his camp on Drury Pond in in Temple, Maine, where in fact we sit many a summer’s evening, talking, talking. Wes likes a beer and a whiskey. I just go for the whiskey.

ly moving.

ly moving.Bill: Read us a passage from the book.

Wes: Stands, finishes his glass of whiskey, addresses the gathering dusk on the quiet pond:

” … My mother’s emotional instability and maltreatment were exacerbated by long stretches of work in the years after my father left. When she wasn’t sewing clothes for my siblings and me, she was sewing for a growing list of customers, and on Saturdays, with a pair of electric clippers she bought for the purpose, she cut the hair of boys in the neighborhood, saving our haircuts for last. It was hard not to jump as the overheated clippers grazed our ears. “Stop squirming,” she would say with a hard slap. “Keep up that whining and I’ll give you something to whine about.” We felt safer when my mother worked at her sewing machine, for though she abandoned us for hours as she sewed, we were nonetheless spared her punishments. Eventually, however, her day-and-night bouts of sewing led to her hospitalization for exhaustion. When she returned home and the neighbors who had housed Paul, Johnny and me deposited us, we had two reasons to obey and please my mother, not only to avoid punishment, but to make her less vulnerable to the emotional stress that had dispersed the family. In Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift writes about Brobignagia, the land of the giants, where his hero meets up with an unpredictable, moody girl who is so much bigger than he is that she can hold him in her hand. Frightened she may toss him away at any moment, Gulliver must use all his wit to divert her. Gulliver’s situation with the giant girl reminds me of my childhood, when my psychological security depended on the skills of balancing my mother’s moods.

“Tempestuous as my childhood was, there were occasional good days, when my mother seemed unburdened by her troubles. On some of the best of them she read me the stories of a fictional black boy named Little Brown Koko that were serialized in the magazine Woman’s Day. Why did she choose these stories about a black child? I asked her recently, and why did she purchase black dolls for my brothers and me when we were children? Because, she answered, when she went to Columbia, Missouri, as a girl to live with her cousin, she saw in a neighbor’s house something she had never seen before: a black maid who was treated cruelly by the whites she worked for. “She wasn’t even allowed to have her own name,” my mother said. “They called her ‘Hannah,’ which seemed to them more like a maid’s name than her actual name did. I made up my mind right then that when I had children, I would make sure they cared about colored people.”

Her attraction to Little Brown Koko drew me to him as well and led me to create, with her help, my first book. This slender volume, bound by cardboard, took Koko’s name as its title and contained cut-outs of all the stories she read to me. Significantly, the stories featured two characters, Koko and his mother; the father of the family is absent and never mentioned. In the only story I remember, Koko disobeys his mother by visiting the watermelon patch. As he eats a watermelon, night comes on, and for a time he can’t find his way home. The little boy is not only frightened to be lost, but scared of the whipping he will get for disobeying. But when he arrives home at last, he is relieved to find that his mother speaks kindly, rather than punishing him. Racist as the story of a black boy in the watermelon patch seems to me by hindsight, this episode of Little Brown Koko ended in the very way I might have wished my own episodes of misbehavior to end. Hearing my mother, who had switched me so often, read the outcome aloud has no doubt made the story stick with me all these years. As she read it, did she wish on some level for kindness in her own childhood? Whatever her thoughts may have been, I see looking back that my book about Koko is related to the narrative poems I later wrote, some of them about people outside the social mainstream, and others about the psychological meanings of family and home….”

Bill: Beautiful. And it’s a great book. See you at the library.

Wes McNair is the author or editor of 18 books, including poetry, essays, and anthologies, and now a memoir. When you meet him, say the phrase, “There will be fighting,” and see if he smiles. Hear him talk about The Words I Chose on New Hampshire Public Radio, here.

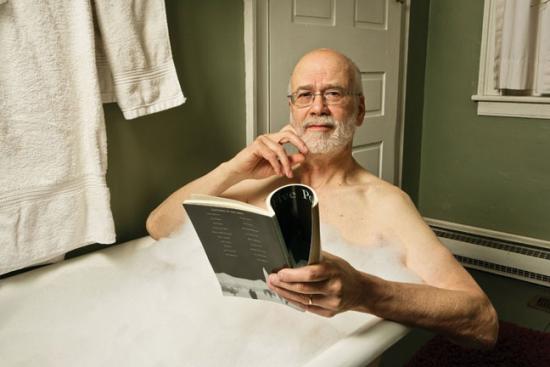

Wes, I mean, Mr. Laureate, I love this deeply! “Take Heart” and “The Maine Poetry Express” are clearly the brainchild (children)of a visionary. Making poetry more available to the general population through a couple of simple initiatives – amazing! And these are ideas, as you noted, that did not die on the branch! Everyone’s a poet. I’ll definitely buy your book to hear more of your story when it comes out. But reading in the bathtub – risky behavior!

PS – I just finished a great book, one of the best I’ve read in a long time, “The Poets of Pevana” by Mark Nelson. Set in medieval times, the main characters are poets who inspire others to act through the passion of their convictions, unleashed in the annual Poet’s Competition at the village’s Hgh Summer Festival. Not my usual genre, I read the intro and first chapter and was hooked. So enjoyable, it was hard not to turn it over and start right back through it again when I was done!