Guest contributor: Sebastian Stockman

Table for Two: An Interview with Julianna Baggott

categories: Cocktail Hour / Guest Columns / Table For Two: Interviews

Comments Off on Table for Two: An Interview with Julianna Baggott

You’ve never heard of Harriet Wolf, one of the 20th Century’s great American writers. But don’t feel too bad — neither had an unnamed faculty member in the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program.

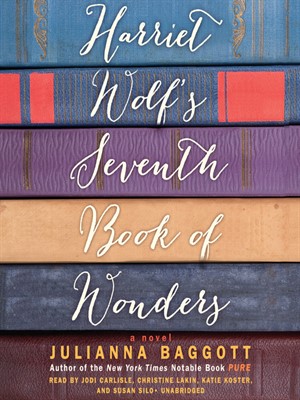

“I gave a reading at VCFA to a bunch of writers,” says Julianna Baggott, whose novel, Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, imagines the existence of a seventh book in the Wolf oeuvre, a memoir that exposes the “true stories” behind Wolf’s six other classics. “And a couple of writers, well-known writers, came up to me afterwards, and said, ‘you know, I’m really not familiar with Harriet Wolf’s work.’

“And I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t think I made that clear — she doesn’t exist.’ So, then I thought, well, let’s not make that clear, let’s build a little bit of her lore…”

Part of building lore included a website for the “Harriet Wolf Society,” comprising academics and others devoted to the study of Wolf’s six novels, a series of books that follow the characters Daisy and Weldon from childhood to death. The genres age with the characters from children’s novel to magic realism to realism to apocalyptic dystopia to a meta-fiction.

Part of building lore included a website for the “Harriet Wolf Society,” comprising academics and others devoted to the study of Wolf’s six novels, a series of books that follow the characters Daisy and Weldon from childhood to death. The genres age with the characters from children’s novel to magic realism to realism to apocalyptic dystopia to a meta-fiction.

In Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, we follow four different narrators: Harriet herself, as she presented herself in her until-now “lost” seventh book, a memoir detailing the real-life love story behind her successful series; Harriet’s lone daughter — Eleanor — who hated the books that, she intuited, kept her from ever knowing her father and gave the world a claim on her mother; Eleanor’s two daughters, the rebellious Ruth and the sheltered Tilton.

Though it centers on a reclusive Great American Writer and her descendents, none of whom exist, the book is full of real-life places and incidents from the Maryland School for the Feeble-Minded (where Harriet spent a big chunk of her childhood) to a plane crash on the Eastern Shore of Maryland (which precipitates the abandonment of Eleanor and her daughters by their husband and father).

This all sounds exceedingly complicated, but Baggott builds a complicated world full of convincing coincidence and conflicts. In The New York Times Book Review, Dominique Browning called the book “a post-and-beam structure, a framework of sturdy supports locked into place with no nails, just fine, firm dovetail joints.”

That sturdy structure is doubtless one of the reasons Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders was named to the Book Review’s list of 100 Notable Books for 2015.

A novelist, essayist, and poet, Julianna Baggott has written 18 novels under her own name as well as the pen names N.E. Bode and Bridget Asher. She has published volumes of poetry and work for young adults. She’s so prolific that it seemed imperative to ask about the time it took her to write the intricate and affecting Harriet Wolf.

Sebastian Stockman: You say in the acknowledgments that you worked on this novel for 18 years, and that it went through lots of different drafts. Is the gestation period always that long for your books? What made this one more difficult, or what made it take so long?

Julianna Baggott: I’d published my first three novels, literary novels, under my own name. And as The Madam was coming out, things were going badly for that book, and … really I thought it was probably the best of the novels that I’d written. But honestly I think what happened was I just got kicked off my game as that book was coming out, and not only kind of lost confidence in myself as a writer — actually, I don’t know that I lost confidence in myself as a writer of literary novels, I lost heart, I suppose.

And, I needed to keep writing, because I’m a writer and it’s how I process the world. It’s how I breathe. And so, from there on out I really tried to create all these different ways to not put myself out, and not put my most literary ambitions out into the world.

SS: Oh wow. That’s really interesting.

JB: Yeah, so I mean, I might have already been writing for kids by that point, but N.E. Bode existed by that point. Bridget Asher was born shortly thereafter. I would collaborate with others. Honestly … the Pure Trilogy ended up literary and had good critical success, but that was for me definitely another way to disguise myself to myself. That was me writing what I thought was a thriller. I think it ended up to be a poetic thriller, or something. <laugh>

But, I really had an incredibly specific kind of writer’s block. I couldn’t come to do the job that I really thought I was meant to do. … But, I found all these other ways to continue to write.

SS: In any case, it sounds like you put Harriet Wolf aside for quite awhile.

JB: Yeah, well, I would come back to it, and every time I came back to it, I would fall into it, but I was a slightly different writer.

You know I would come back to it, and it was Eppitt’s story for a long time, and I actually had the beginning of the novel published in 2001 from his perspective.

I would come back to it in all these different forms and all these different ways. And every time I came back I would figure out a new way in, and I would bring with me my slightly different ambitions with language, and my slightly different obsessions and what was important to me. And then I would walk away from it because I would say ‘well, I don’t actually want to publish this.’ ….

So I would write something else — happily so … . Writing those other novels taught me an incredible amount. I love those novels. I stand by them.

But then I would come back, and I would come back again. And once I came back I was collaborating not with just my initial attempt at the novel, I was collaborating with the person who came before me — who was me but a different version of me. And it just got more and more layered. And then of course it kind of became too big in my head to tackle.

I’d written a screenplay, actually, that’s kind of the present day — not present day, but set in 2000 — from Tilton’s perspective. And at that point Tilton was a male character. Then I kind of figured out that piece of it, that the historical novel was set against this present-day narrative. And then I figured out that they were all women. Then, I eventually just sat down and wrote it.

It’s funny because people have been writing to me saying “it’s such a relief to hear it took you 18 years.” And I say, “No no no no no no no, you misunderstand. Do not — this is not a good way to write a novel. There’s nothing to learn here, look away.”

SS:

Although, I would say, I think the layering effect you talk about shows up in these Rashomon-like versions of the same events from various perspectives.

But it’s not — it feels so organic, I guess is the word I’m going to use even though I wanted something better.

We get these certain concordances where it all feels really natural. One of the things that struck me was between Chapters 9 and 10 when Harriet is going home. The young Harriet is leaving the Home for the Feeble-Minded, and chapter 10 starts with Ruth, Harriet’s granddaughter, arriving decades later, at that same house, after years of her own estrangement from her family.

Things like this made the coincidences feel right without feeling overdetermined.

JB:

I don’t think I understood that the house was a character until long after. … In my head it wasn’t until I rewrote the book that I really thought ‘this is the same house. … You have to make this the same house.’

There’s this Tom Stoppard play called “Arcadia” which ends with multiple time periods, and the actors are all on stage at the same time. There’s one present-day narrative and one past narrative.

And the actors being on stage through time and at the same time was so resonant with me. And by the end of the final draft I really did want the reader to feel that things were happening at the house almost at the same time, even though they were in different time periods. I wanted you to feel this character moving through this room even though it was many many years before this [other] character was sitting at the dining room table that [the first character] is passing.

SS: The house is almost a member of the family.

JB: Well, it has an umbilical cord. It squats over them like a bird in a dream that one of them remembers the other one had. It has a lung. It is very alive.

SS: The other thing I love about this book are its convincingly complicated family relations. When each woman in turn becomes a mother, Harriet and then Eleanor and then Ruthie, it’s almost as though they’re fighting the last war in some way, you know?

It’s about the ways our parents mess us up despite the best of intentions. Or — no matter their intentions, there are always unintended consequences.

JB: And that sometimes your parents are in an argument with their parents. And sometimes you’re arguing with them in daily life, ‘I’m going to parent in contrast to you.’

SS: There’s also the way Eleanor fails to protect Ruthie, her older daughter, and then overcompensates with her younger daughter, Tilton. This is what I mean about the structure’s seeming so natural without being forced. Eleanor overparents Tilton, and that gives Harriet and Tilton something in common because they were both overly-sheltered people.

And what about this photo in the frontispiece? It’s captioned “Harriet Wolf with the man presumed to be Eppitt Clapp. (date unkown).

JB: My daughter, my 20-year-old … went back to my parents’ house and spent a month one summer scanning old photographs; she’s an artist.

And so when she came back she had these photos all scanned, and I saw this photo, there were a couple of them, and they’d say “Ruth and Rosebud.” Who the hell is Rosebud?

Ruth, I figured out, was my Aunt Ruth, who never had children and whose sofa we were probably sitting on when we were looking at the photographs. But I was like ‘Damn… Rosebud is fine.” Who the hell is he?

I asked my mom, and she said, ‘That’s your Uncle Jesse.’ Ruth and Jesse married. I only knew Rosebud, my Uncle Jesse, as an old man, not as … this gorgeous gangster.

SS: And the decision to use it in the book? It really does the job of smudging that line between fact and fiction, because that photo and I knew you’d done a bunch of research, and I thought “Wait, these people she definitely made up. I know this.”

But it put this little seed of ‘I’m not sure’ in the back of my head. Like, ‘is there a Harriet Wolf?’

JB: Right as the book was going to press I sent this photograph to my editor and I said this is the photo we’re going to put on the [Harriet Wolf Society] website — you know, a “found” photo of Harriet and possibly Eppitt, we’re not sure who this guy is — and he’s like ‘Let’s put it in the book.’ So we put it in the book

SS: Well, yeah, I think it totally works, because it did throw me.

Also, it made me wonder, this photo is something your daughter found after you were well on your way to finishing. But you made up another artifact we don’t see, but that Harriet describes — one photograph of her family.

But I’m also wondering: because you did research, and because this book was with you for so long, were there any sort of artifacts or talismans that you used or carried with you to help orient you to the world of the book?

JB: Yeah, there is a big fat envelope. And we’ve moved six or seven times in the last 10 years …

SS: That’s not fun!

JB: It’s not fun. But I’ve kept this — Eppitt was the name of the book, and it has “Eppitt” written on it. Inside there’s a plane crash article … and just a number of different artifacts. One is that 1911 biennial report which I had gotten a copy of when I went and visited [The Maryland School for the Feeble-Minded].

I had that for so long. As soon as this book was coming out we moved again last October, and that’s the one envelope I can’t find. The universe sucked it up.

But there’s one photo [Harriet] talks about, of the children on the lawn, and she feels like that’s her. There are pictures in that 1911 report, of children working and children in classrooms weaving. So that might actually be a photograph, the one of children running on the lawn. It’s so vivid to me, it might actually be a real photograph.

SS: In Harriet Wolf you’ve created this fixture in American letters, sort of a J.D. Salinger-type, or maybe Fitzgerald, somebody who had an influence on generations of schoolkids or generations of readers.

And, while we get some plot summaries, we don’t see much of her own words. Because you went through so many drafts, how much of Harriet Wolf’s oeuvre did you write, or did you just sketch out plots?

It seems like there’s a tricky thing there, right, of telling the reader this is a classic of American literature and —without seeing much of the prose — we sort of have to take the author’s word for it.

JB: Right, and in the previous draft, before Ben edited it, there was much more. He wanted me to cut. My first job was just to cut 9,000 words. But even then, he felt like less was more in terms of the books behind this book. So I knew that I was going to have to trim those back, but previously there was much more of them.

I can’t say that I know the plots; it’s not that I plotted them. It’s much more like I imagined things.

SS: The arc. We don’t get plots, I guess, but we get the flavor of each book, as the series moves through genres and sort of grows up with the American reader. It grows up with the 20th Century, almost.

JB: Right.

SS: When you did write more of the Harriet Wolf stuff, was that also pressure, or was it more like donning one of your pseudonyms?

Because obviously we don’t sit down and consciously try to write a classic of American literature unless you have a character who has written one.

JB: Right, The last book is memoir, so she’s in a different genre again. The final genre is memoir.

I think that my main thing was just to have the images sustained for the reader. And also there’s a line that goes throughout the whole thing, her most famous line, and you figure out who said that line in real life and what it meant to her in the moment.

SS: Some of her secrets are revealed, in a way…

JB: And I think that’s one of my kind of great sadnesses as a writer. … I don’t get to tell you guys where the great lines come from.

My own life, I’m never going to share with the reader. I’m not. I’m never going to write memoir. I mean if I could barely write this, I’m certainly not going to have the courage — I can barely hand myself over as an author; I’m certainly not going to be able to hand myself over as a human being —

And so, you know, there are so many times when it’s really like this incredible love affair that I have with my husband, this incredible life that I have with four kids that’s just like, amazing and hard and I love them so much and

<silence>

SS: Did I lose you?

JB: No, …

SS: [belatedly and thickheadedly realizes she is crying] Oh, goodness, I’m sorry, take your time. Take your time, I’m sorry.

<silence>

JB: Anyway, it’s just a privilege to be alive.

ME: Yeah, absolutely. Gosh.

JB: And I never get to… I never get to share that part, you know? And so in some ways, I am a liar. You know, as a writer.

And I’m not courageous. So, in some ways I’d love to hand over some secret book of the truth of how messed up and painful and incredibly gorgeous and heartbreaking my own life is. But I never will and so I guess maybe that’s the main wish fulfillment of this book.

In other interviews I’ve said that the wish fulfillment of this book is that she gets to be a hermit. God, I’d love to be a hermit. I’d love to make enough royalties to be a hermit. But in fact maybe the real wish fulfillment is that she got to be honest.

As a fiction writer I’ll never be that honest. Maybe to my kids or whatever. But each book I write, in almost every line, every place on every page, I write from memory.

So every. single. thing — is my life. It’s what happened that day, what happened that morning, y’know? It’s me as a child; it’s my mother. It’s my own daughter. It’s just such a strange—I guess that is the wish fulfillment — that I will never be able to express that to readers, to explain how intimate we’ve been.

We’ve been intimate for all these books and all these pages. And they’ll only think I made it up.

SS: You have those hints through Harriet: “I would like to say that I made up all of the books, invented everything. But really I’m more like the addled priest who wakes up each morning and picks up his wicker basket to fill with every dirty thing he finds and then spends his nights hunched over polishing buttons and spoons.”

I thought that was a beautiful image of fiction-writing. It made me think of something the poet Kay Ryan said how she spends her days gathering string.

JB: That works. I mean this book is about a knot.

ME: I was trying to avoid that hacky interviewer question of “how much of this book is you?” But really I like that notion of Harriet’s manuscript as wish fulfillment. So, Eleanor hates fiction, or maybe that’s too harsh?

JB: No, I think she hates fiction.

SS: So Harriet loves fiction because it’s her chance to sort of fix the world she’s been handed. But for Eleanor fiction is what’s keeping her father from her, in some ways?

JB: She hates fiction like one might hate a stepfather because he takes up so much time and attention, and because he’s not the truth.

SS: And is there — since we’re on this idea of taking things from your own life — is that a sort of not wish fulfillment, but is Eleanor saying something there that you sometimes maybe want to say, too?

JB: Oh, my feelings about fiction, or about my father? I have this incredibly lovely father.

But yeah, about fiction, I hate it, too. I got to say a lot of things that I wanted to say about writing. The first version was much harsher, much harsher. And that was another thing, Ben was like ‘maybe you shouldn’t quite hate the reader so much’?<laughs>

But I think that I’m a writer who very much loves the reader. And I dote on them and I think about them and I adore them. It’s definitely my worst flaw as a writer: I completely over-love the reader.

SS: Why is that necessarily a flaw?

JB: I don’t know — where do their desires start and where do they end? And where do my instincts and desires start and end? And do I sometimes discount my needs as a storyteller and my stylistic needs…?

And sometimes I write a draft for me and say “OK, that was for me, now actually translate it for the reader.” …

That overlove — they [the readers] have too much of my attention sometimes. I bow to them instead of what might be to my needs. … Steven Spielberg talks about this: “My early films are all about my relationship to the person seeing them.”

He’ll never give up on the viewer. He’ll always overlove the person who’s watching his films. In writing my goal is to try to find ways to be of service to my characters … and those are the best writing days, when they take charge. And sometimes the reader is not the best person to be bowing to.

Definitely I have a love relationship to the reader and I certainly think about them, but also there’s the counterpoint to that. My relationship to the reader is not an easy one. I don’t know what book they’re reading.

If this is a collaboration… the St. Louis Arch was off by a few inches when they built it. I’m building the St. Louis Arch, hoping to meet them perfectly. There’s no way our arches can meet in the middle.

That’s a very, very strange collaboration. And also, because I’m a writer, I’m someone who is the composer who never hears the audience clap. They’re just not there. There is no audience. I write in a vacuum. It’s a strange thing to think so much about someone who is so imagined.

SS: They’re not there and you love them too much.

JB: Right. Exactly. That seems doomed!