Stay Awake for the End is Near: Literature Meets Slumber Party at a Moby-Dick Marathon

categories: Cocktail Hour / Reading Under the Influence

4 comments

Call me Willy. My father does.

.

I traveled down from the forests of Maine through Boston and further yet to the sea like a young man in another century looking for his ship. My paler but still daunting adventure was simply this: attendance at the sixteenth annual marathon reading of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Twenty-five hours, 160 readers, “light whaleship fare” the only sustenance promised.

The museum is situated within sight of the Acushnet River, from which, 171 years before (and nearly to the day, January 3, 1841), the young Herman Melville embarked on his own great adventure, sailing with the whaling vessel Acushnet on a trip that would take three years. His dispatches from that voyage, especially his reports from the Marquesas Islands (where he jumped ship), and then Typee, his first novel (with its “savage” but noble maidens who wore nothing but “the garb of Eden”), quickly made him the Hugh Hefner of his day. Typee was a bestseller. Moby-Dick, however—published five years later—bombed, and would have to wait for posterity to catch up.

I forgot about rush-hour traffic through Beantown and so arrived at the museum barely in time to catch the marathon’s keynote talk by Professor Timothy Marr: “Moby-Dick in American Popular Culture.” I have a flock-counting compulsion from my days as a birder, and subtly as possible I determined that there were nearly 190 souls in the museum’s well-appointed lecture hall, more than I’d expected. Mostly they looked like professors and professionals, NPR listeners—like me, that is—well dressed and well heeled and in their fifties or over, not a monkey jacket in the crowd, not an ivory peg leg, not a harpoon and no whale pikes, not so much as a cannikin of spermaceti, though the speaker bade a young man in the front row roll up his sleeve to expose a huge tattoo of a leaping Moby Dick (Melville gives the animal no hyphen, only the book’s title gets that).

Polite applause, approving nods.

And the lecture, well, it was funny and also prodigious, plenty of fair-use PowerPoint proof that Moby-Dick is deeply embedded in the American psyche, from film to video games to television to Moby-printed sleeping bags, which Dr. Marr suggested some of us might need come the wee hours of the marathon.

I mingled with the crowd, found Melville people from all over the United States, but also from Holland and England and Mexico, and even Tahiti (in the person of Keitapu Maamaatuaiahutapu, who is the fisheries minister of French Polynesia), all come to New Bedford to take part in this most obsessive of celebrations. The talk was not small talk,

but all Moby-Dick, which, perforce, is big talk, and I found myself explaining over and over again that though I hadn’t read the damnable book for over three decades, I counted it as one of the great influences on me as a writer. It was Moby-Dick, in fact, that had helped me separate my fiction from my nonfiction, that made me look to nature for my subjects, that set me free in the language. I adored great Melvillean sentences like this: “And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.”

I put my name on a standby list of readers in the not exactly soaring sixty-third slot and asked the volunteer on watch what my chances were.

“Unlikely,” she intoned. “Very unlikely.”

“But not impossible,” squawked a private parrot in my ear.

Late, having found some dinner in the beautiful historic district around the museum, I paced the cobblestones down to the waterfront, gazed upon the idled fishing fleet (with fisheries depleted and even crashed, voyages out are strictly regulated), then headed home to my pleasant hotel to get a good sleep: I sorely meant upon the morrow to hear as much of the reading as possible, to snooze little, to prop my eyes open with marling spikes if that were what it would take.

That night, tossing and turning in anticipation of the voyage ahead, I had a vision of a tattooed cannibal bearing a shrunken human head and crashing into the room—he appeared to have his own keycard, a scrimshawed thing as slim and shiny as a Javanese baleen shoehorn!

“Your roommate,” said the front desk when I called down. The intruder’s name, as it turned out, was Queequeg (straight from the first chapters of Moby-Dick!), and he joined me in bed, no care that my sleep number might be different from his, threw his leg over mine, and faces close, we talked the glistering stars away.

#

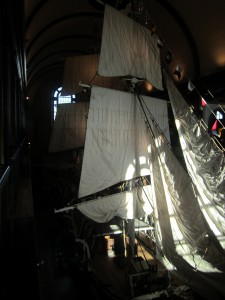

The elegant Bourne Building at the New Bedford Whaling Museum houses a single tall room dominated by a half-size replica of the whaling vessel Lagoda, built by a daughter in honor of her captain father—half-size yet enormous—the biggest ship model in existence: fifty-nine feet from figurehead to stern, fifteen sails fully rigged and reefed, mainmast fifty feet high, very nearly touching the high, vaulted ceiling.

The crowd gathers as Saturday noon approaches, first a few, then a score, then a hundred, and still they come, record numbers—not enough seats—so they’re sitting on the floor, on the window benches, on the stairs, and finally in the Lagoda itself, odd perches on half-size barrels and half-size buckles and hatches and capstans, everyone bearing a copy of The Book, four hundred people or more, part of the twenty-six hundred that will come through the museum this auspicious weekend.

Management is glowing. You can pick out board members by their grins.

The sound guy tests the mike: “Call me, um. Call me . . . what is it?”

And no one laughs. In fact, no one pays attention. He’s not funny. He’s certainly not Ishmael, and we’re waiting for Ishmael. At about eleven-thirty, one of the Melville scholars on hand begins reading the etymology that starts the book—the word whale traced down through the centuries and across the languages—declaiming unnoticed and unheard from the very high balcony, a grand oval running around the room at about crow’s nest height (make that half-size crow’s nest height), over the great, echoing chatter below. After the etymology, the scholars turn to Melville’s “Extracts,” page after page of quotations about whales and whaling, which he claims were collected by a “sub-sub-librarian.“ The scholars do their best to make it loud. The crowd begins to notice, starts to turn pages, to find the quotations at hand in their rare first editions, their Norton critical editions, their Folio Society editions, their dog-eared college paperbacks, but few stop talking: the extracts aren’t the opening we’ve all been waiting on, and it isn’t noon yet, the advertised starting time.

And no one laughs. In fact, no one pays attention. He’s not funny. He’s certainly not Ishmael, and we’re waiting for Ishmael. At about eleven-thirty, one of the Melville scholars on hand begins reading the etymology that starts the book—the word whale traced down through the centuries and across the languages—declaiming unnoticed and unheard from the very high balcony, a grand oval running around the room at about crow’s nest height (make that half-size crow’s nest height), over the great, echoing chatter below. After the etymology, the scholars turn to Melville’s “Extracts,” page after page of quotations about whales and whaling, which he claims were collected by a “sub-sub-librarian.“ The scholars do their best to make it loud. The crowd begins to notice, starts to turn pages, to find the quotations at hand in their rare first editions, their Norton critical editions, their Folio Society editions, their dog-eared college paperbacks, but few stop talking: the extracts aren’t the opening we’ve all been waiting on, and it isn’t noon yet, the advertised starting time.

Finally, an actor takes the stage in sailor’s duds, red scarf. The crowd hushes. The fidgeting quits. He’s my age, too old by a couple of decades for a voyage of more than an afternoon’s bluefishing, or maybe a largemouth bass competition on the sports channel.

“Call me Ishmael,” he says plainly, and we’re off, reader after reader, all shapes and sizes, and more importantly, all levels of projection, enunciation, and diction, from none to tons.

#

At about one-thirty—we’re only fifty pages in—the entire gathering wanders across the street to the Seamen’s Bethel, an old wooden church that Melville knew well and that has a place in the novel. When we’re settled in the gorgeous historic pews, the actor playing Ishmael comes back for another turn and begins the reading of chapter 7, “The Chapel.”

The preacher arrives, an actual minister playing Melville’s, and this good man acts out his fictional counterpart’s climb to the pulpit; in fact, he climbs the pulpit, which is built as the prow of a boat. “Starboard gangway there!” he cries. “Side away to larboard!”

The Book has come to life!

The novel’s famous hymn, nothing more than a poem on the page, looms ahead. Ishmael tells us it’s going to be sung, and just as he says it, a wheezing organ begins to play. All heads turn to the back of the Bethel—the man playing the tiny keyboard looks the part, modest and reverent and shabbily shorn. A dashing fellow in ascot and knickers stands, strides to the front, hat at his breast. According to the program (a lot of rustling in the room), he’s the acclaimed operatic tenor Jonathan Boyd. And just as the book says, he “burst[s] forth with a pealing exultation and joy” (never mind that it’s supposed to be the minister): that is, he sings the actual hymn in the book! (To music written for the Gregory Peck movie version, ca. 1956, but never mind again.) My heart could burst, the make-believe moment is that real. Our tenor rattles the old timbers of the church with his high notes, the preacher muttering along, enraptured.

#

Back in the museum, the readings continue: impressive children, dramatic teens, many a middle-aged enthusiast, a man of ninety-six, people of special needs, deep Taunton accents, overseas accents, too, mumblers and stumblers followed by elocutionists and hams, all in front of a Moby mural and under loomingly impressive humpback skeletons—enormous ribcages, plenty of room for Jonah in there, and for a score of the rest of us, too. Those vertebrae, they’re the size of car tires, all linked in the frozen suggestion of power, something to lean back and study when the words grow fuzzy in my hands, when the old neck needs stretching.

The watch officers don’t seem to be calling anyone at all from the standby list. Conversation is not tolerated. My dream of snarky background interviews has been harpooned. A volunteer holds paddles at ready, one saying “Shhhh,” the other “Hush Please.”

As the afternoon progresses into evening, I fall into a kind of literary hypnosis, begin to dream my way into Melville’s obsessive descriptions of men and equipment, the endless (and endlessly wonderful) considerations of whaling lore, the aching philosophical threads, the soaring spirituality. Suddenly, completely, Melville grabs me by the soul. This way of life gone past! These lives gone past! Life itself going past! The very possibility of life, passing! Even in its throbbing optimism, Moby-Dick is an elegy, a threnody, a tragedy, our own.

In its time, Moby-Dick represented a shift in humankind’s relationship to the world. No longer entirely powerless before nature, merest people had begun to tip the balance in an age-old war of survival, me and you against the wild, the stakes tilting toward what looked more and more like dominion, as promised in the Bible. And the more thoughtful observers of the time—Melville among them—had come to realize that people were capable of destruction so thorough it was godlike. In the mid-nineteenth century, the North Atlantic whale fishery was already done for. Thus the years-long voyages to the far reaches of the globe, the Pacific deeps. And to waters so clear that a sailor as humble as Ishmael could look down even through carnage to hope itself: “For, suspended in those watery vaults, floated the forms of the nursing mothers of the whales, and those that by their enormous girth seemed shortly to become mothers.” Newborn whales, nursing! With fulsome and poignant detail of how this was accomplished, no less.

Melville was aware of what would soon be lost, and keenly aware that in the end, the winning of Ahab’s hubristic war on nature would be suicide on a global scale. He wondered “whether Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc; whether he must not at last be exterminated from the waters, and the last whale, like the last man, smoke his last pipe, and then himself evaporate in the final puff.”

The whiteness of the whale is a horror to Ahab. But what could the whiteness of the whale mean to us today? Self-destruction is an alluring path. Our wants are boundless, our multiplication unstoppable. I clutch my iPhone, think of the five hundred miles I will have driven by the time this adventure ends. Our harpoons are more thorough, the devastation more complete, the whiteness like blindness.

We stagger on unseeing! Toward the abyss!

You can’t help thoughts like that (nor the exclamation points) after nearly twelve hours of Moby-Dick.

#

About eleven p.m., a man in a yarmulke steps up and reads from a Hebrew translation (others have and will read in Italian, Spanish, Japanese, and many other languages—Moby has had a world audience for over a century). I find myself dozing, not the reader’s fault; I’ve just got too many sentences in my head. But he can’t see me and those who can don’t mind. There are other snorts and starts around the room. I get up reluctantly and step out for air, get a coffee up the street, find familiar museum faces at the bar, shots of grog, no doubt, a copy of Moby-Dick in every hand, bartender delighted: this is January, and she’d expected a dead shift.

I don’t normally drink coffee. Very suddenly, I’m ripped.

By two in the morning I count only twenty-six people in the seats before the dais, another twenty or so on a roomy landing upstairs where sleeping bags are allowed—“Occupy Moby,” they’re calling it. By three it’s nineteen intrepid souls, older folks, mostly—the stamina of age. And the number never goes below that, starts rising by five o’clock as the windows lighten with approaching dawn.

I am drifting, drifting like Queequeg’s coffin, drifting on rough waters. I sleep and wake; I take short, somnambulant walks; I peek into the museum’s galleries, the sublime collection of paintings, the stuffed seals, the walrus head, the many gargantuan whale skeletons and humble dories, the depressing collection of whale-oil products (some fairly recent), the hooks, the knives, the boiling vats, the gear I’ve been hearing about, the rigging, the endless photographs, this record of carnage, careless greed upon careful commerce.

That the book continues when I return to my seat each time is comforting. I hear new depths in the text, remember odd details from readings long past, keep being surprised by how little story there really is: guy is obsessed with the whale that took his leg; guy destroys himself and his entire crew in pursuit but gets the whale, too. I’m surprised yet again by the way even those scraps of plot are so brilliantly illuminated by the supposedly discursive and supposedly endless expository sections that by the time you hear about, say, a harpooneer in action, you are an expert on man and equipment alike and can judge for yourself the steadiness of his hand, the quality of his game.

#

Noon Sunday and the crowd has swollen back up to nearly four hundred people. Locally beloved Massachusetts Congressional Representative Barney Frank is reading. He looks well rested. We’re only pages from the end of The Book. Barney (on the verge of retirement) gets a big hand.

The penultimate reader is Peter Whittemore, Melville’s great-great-grandson, an appealing, lanky fellow. He chokes and sobs openly as he reads the last words of the body of the book: “Now small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its steep sides, then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.”

Ahab has completed his self-destruction and the destruction of his crew.

Ishmael, though. Where’s Ishmael?

Melville added an epilogue after British critics asked (derisively) how a dead man could have told the tale. And so our intrepid narrator is found floating on Queequeg’s coffin, and delivered home to his desk.

Finis.

We bleary listeners file out, muted talk, the air outdoors a relief, very like leaving a funeral, a funeral that you suddenly realize has been in progress a long time and yet has only just begun. The couple ahead of me falls into one another—I recognize them from the overnight—cheerful, stocky folk from Stone Mountain, Georgia, thick accents, she in improbably high heels. He laughs at her groan and she laughs at his boom and the rubbery-legged college kids ahead of them turn and laugh too, and one of them stumbles. He catches himself on his friends’ shoulders but the momentum’s too great and all of  them go down. The couple can’t avoid them, can’t stop in time, and they stumble too—but the young men prop them up in self-defense, laughing, all hands raised, and the Georgians manage to stand. The folks behind us pile into me (we’re all in the same boat), and I bump the couple back into the kids, have to bear-hug the man to keep us both on our feet—and now I’m laughing and he’s choking with it, big arms around me, his wife a fit of giggles, the college kids shouting in fun, the people behind pressing up laughing and yelling ship stuff—Gangway! Gangway!—and the laughter is itself funny and such a relief, really a relief, and we’re all laughing harder yet, all trying our best just to get out of the way, just to make room, laughing and shouting, sailors giddy with leave, with visions of the sweet, great, abstracted calves of whales as they suckled in Melville’s clairvoyant deep, oblivious seamen all of us, full of the future all of us, the sunlight brilliant and shocking, the long night far behind, the language of Melville oddly ahead, forever ahead, always ahead.

them go down. The couple can’t avoid them, can’t stop in time, and they stumble too—but the young men prop them up in self-defense, laughing, all hands raised, and the Georgians manage to stand. The folks behind us pile into me (we’re all in the same boat), and I bump the couple back into the kids, have to bear-hug the man to keep us both on our feet—and now I’m laughing and he’s choking with it, big arms around me, his wife a fit of giggles, the college kids shouting in fun, the people behind pressing up laughing and yelling ship stuff—Gangway! Gangway!—and the laughter is itself funny and such a relief, really a relief, and we’re all laughing harder yet, all trying our best just to get out of the way, just to make room, laughing and shouting, sailors giddy with leave, with visions of the sweet, great, abstracted calves of whales as they suckled in Melville’s clairvoyant deep, oblivious seamen all of us, full of the future all of us, the sunlight brilliant and shocking, the long night far behind, the language of Melville oddly ahead, forever ahead, always ahead.

[Stay Awake for the End is Near originally appeared in the gorgeous May/June issue issue of Orion Magazine. Subscribe!]

[Follow me on Twitter: @billroorbach]

[And Like Bill and Dave’s on FB, for heaven’s sake, right up there^!]

This is so rich and pleasurable, Bill. You deftly weave a dozen threads masterfully, handing the reader fine linen to turn in their hands. From your dream sequence, you’ll have to pardon me, instead of Queequeg entering your room, I expected to hear, “Oh no, it’s Dave!”, from your Oct. 12th post.

When the last ax cuts the last tree

When the last drop of oil spills into the sea

When our children wonder what it was like, and long to be free

When they lay the last stone, where will you be

Thanks, Tommy!

Lovely and powerful, Bill. What a book, what an experience captured.

What a book is right… It was wonderful to hear it, dream it, live it all at once…