Guest contributor: Crash Barry

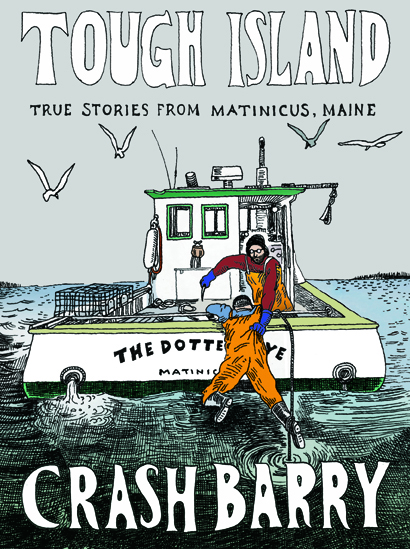

Serial Sunday: Tough Island: True Stories from Matinicus, Maine, by Crash Barry

categories: Cocktail Hour

Comments Off on Serial Sunday: Tough Island: True Stories from Matinicus, Maine, by Crash Barry

Episode Three

[To read Episode 2, please click here][To start at the beginning with Episode One, please click here]

Four-thirty a.m. came quick. I was awake and ready instantly, thanks to my rigorous Coast Guard regime of pre-dawn drug boardings and search-and-rescues. Donald and I drank a cup of tea and ate toast with margarine, then headed to the shore in his beat-up Chevy. It was still dark as we climbed down a ladder attached to the Steamboat Wharf and into his 14-foot aluminum skiff powered by a 10-horse outboard. He stood in the stern and motored us to the mooring. Other men were also en route to their boats. And a couple were already steaming out of the harbor into the dawn. Donald didn’t wave or acknowledge any of them. They ignored him back.Aboard The Dotted Eye, we pulled on our oil clothes, boots and gloves. Donald started the boat, then showed me the way he wanted the bait bags filled. Six fish per bag, more or less, depending on the size. He showed me how to attach the wash-down hose to the lobster holding tank. And how to use the banding pliers. Then he told me to release the mooring and we were underway.

Standing on the bow, I inhaled deeply and tasted the mix of salt air, rotten bait and diesel. As Donald headed past the breakwater and bell buoy, I absorbed the amazing early pink light and energy reflecting from the sky and sea. I was glowing. Vibrating positively. Joyful. In the zone of happiness, reveling in the scene and the scenery. I felt so lucky and happy. To be alive. To be working on a boat. To be living in Maine.

In his mid-sixties, he looked like a caricature of a Maine lobsterman. Salt and pepper beard with no mustache. Arms the size of legs. Legs the size of trees. Hands of a giant.

“WHADDYA DOIN’?” Donald shouted over the din of the engine and gestured for me to join him in the cuddy. “You better fill as many bait bags as ya can,” he barked and pointed sternly. No smile. No glint in his eyes. “ ‘Cuz we’ll be at the first string in five minutes.”

By noon, we were done hauling and tied up at the bait scow. Donald decided to go easy on the new guy and only haul 100 traps. He usually hauled 250 to 300 a day. From a huge bin on the scow, I shoveled herring and refilled the bait box, then washed and scrubbed the boat while Donald dealt with the lobsters.

I knew I could handle being a sternman. Not a hard gig, especially for a fella who could roll with the rhythm of the sea. Easier than being a deckhand on a Coast Guard cutter, that’s for sure. All morning, I filled bait bags, emptied traps of various fish and underwater fauna, while measuring and banding lobsters. My forearms were greasy with fish guts and my hips were black and blue from slinging traps port to starboard, but it was simple work.

“After bait and fuel, I’d guess you made about fifty bucks,” he drawled as we slid a couple wooden crates filled with lobsters into the drink. Donald tied them off to a cleat on the scow. “Whaddya think? Can you do the job?”

“Yes sir!” I said. At the moment, flat broke, fifty bucks was a fortune. Even though the first $200 was paying for my new gear, I knew it wouldn’t be long before I’d need a bank account. “No problem.”

“All right then.” Donald looked at his watch. “Time to go home and have a lousy sandwich.” He coughed and spit into the harbor. “Then we’ll move you to your room.” He spit again. “I’ll tell ya, I’m getting sick of friggin’ turkey bologna.”

Up at the house, in the center of the kitchen table, was a pitcher of the red beverage, three glasses and a bowl of potato salad. Mary-Margaret was busy at the counter. I couldn’t stomach the Kool Aid again, so I grabbed a cup and headed for the sink.

“Be sure to take it from the filtered spigot,” she said, as she placed sandwiches on plates. “The one on the right.”

“Something the matter with the water?” I asked.

“Years ago we had a kerosene spill and it tainted the aquifer,” she explained. “Been ten years and the well hasn’t been the same since.”

“Twenty,” Donald grumbled, pouring himself a glass of Kool Aid. “Twenty years ago.”

“Really?” Mary-Margaret said. “Seems like yesterday. Anyways, 500 gallons of kerosene from the…”

“By Jeezus!” he interrupted. “Mary-Margaret, you’re numb as a hake. How could it be 500 gallons? Our tank only holds 250.” He grunted and spit into his handkerchief. “It was 250 gallons. Besides, there ain’t nothing wrong with the water no more.”

“If you say so, dear.” She nodded and sighed. “Still, we only drink from the filtered spigot.” She smiled feebly. “How’s your sandwich?”

“Great,” I said, even though the turkey bologna on store-bought bread with light mayo and runny yellow mustard was dreadfully bland. “I was starving.”

“You only worked half a day,” she snorted, “can’t be too hungry.”

“I got a surprise for ya.” Donald grinned. His mood seemed to improve after lunch. “I like my sternman to have transportation.” He led me out to a shed in the backyard and slid the door open to reveal a motorcycle. “As long as you’re on the island, working for me, the Hondamatic is yours. One of the perks of the job.”

“Wow.” I had zero interest in motorcycles. My only experience on a bike resulted in a parking lot crash back when I was a Coastie. Pedal power was more my style. “You know, uhhhh,” I stalled. “I really don’t have much luck with motorcycles.”

“Easiest bike in the world to ride,” he assured me. “It’s a Hondamatic. No clutch. Two speeds. Bought it new in ‘78 and it ain’t never been off Matinicus since.”

“Well,” I said. “It’s just that I’m kinda…”

“Jeezus, boy, my granddaughter’s 12 and she loves this bike,” he patted the saddle. “Take her out. Go nice and easy. Look around. Get a feel for the place.”

After driving back and forth in front of Donald’s house ten times, I was ready to go. I rode down to the harbor and took the road out to Markey’s Beach, where I parked and walked the length of it. The tide was halfway to high and the surf broke gently on exposed ledges. I had the entire place to myself, except for a few seagulls frolicking on the wet sand.

After a couple smokes, I drove back to the harbor and parked by the post office, which shared a building with the lone island store. Both were closed. I peered through the windows. Seemed the stock consisted mostly of beer, soda and bags of snack food. The rest of the shelves looked barren.

I wandered over to the end of the Steamboat Wharf to get a good look at the harbor: A rugged little village of brightly painted fishhouses and wharves, mixed with a couple derelict buildings, crumbling, dark and forgotten. A charming postcard.

There was an old-timey telephone booth in front of the post office, so I decided to give my folks back in western Massachusetts a jingle because they had no idea where I was. The answering machine picked up.

“Hi, Mom and Dad, it’s Crash calling.” I paused, trying to think of an accurate way to describe my new situation. “Everything’s great. I got a job on this island in Maine called Matinicus. You can find it on the map. It’s 20 miles off of Rockland.” I paused again. “I made 50 bucks lobstering today, plus all the lobster I could eat.” Both of my parents loved lobster. They’d appreciate the detail. “And I just cruised the island on my new motorcycle. Pretty exciting. I’ll call you again, soon. As soon as I get settled.”

Back on the bike, I zipped up to the middle of the island and took a left at the crossroads, rode past the modern one-room school house and the cemetery of old stones and collapsed graves. Then I turned onto a grassy trail framed by spruce trees that seemed to follow the shoreline to the south. Glimpses of the shimmering sea beckoned me and a long path of sunshine created a sparkling trail six miles out to Matinicus Rock’s infamous lighthouse.

I crept along on my motorcycle, admired the amazing view, breathed deeply the open ocean air and reveled in my good fortune. Perhaps I drove too slow. Or maybe I shouldn’t have taken the Hondamatic off the road. No matter. Suddenly the bike slid and toppled over, pinning me on a hillside sloped toward the rocky shore. Stunned and frightened, but uninjured because the bike was surprisingly light, I squirmed out and vowed to never ride a motorcycle again.

Donald shook his head when I told him what happened. “You’re being stupid,” he said. “You shouldn’t have gone on that trail. Stay on the road and you’ll be fine. It’s a friggin’ road bike for christ’s sake.”

“Well,” I said, eager to forget the incident. “I still think I’d prefer to walk.”

“Suit yourself.” He rolled the bike back into the shed. “Your loss.”

Crash Barry realizes that working as a sternman aboard a lobster boat is a pretty easy gig, especially compared to his time spent refinishing wood floors, demolishing bank vaults, breeding alpacas, milking cows, cleaning professionally and laboring as a print and radio journalist. He now lives near a marijuana grove in the hills of western Maine. His column One Maniac’s Meat appears monthly in The Bollard, and details his exploits as a young sailor in the U.S. Coast Guard. He occasionally blogs at crashbarry.com and his rollicking novel Sex, Drugs and Blueberries and the complete version of Tough Island are available at Maine bookstores and libraries or via crashbarry.com or on Amazon. His latest book Marijuana Valley, Maine: A True Story will be published this fall.

Crash Barry realizes that working as a sternman aboard a lobster boat is a pretty easy gig, especially compared to his time spent refinishing wood floors, demolishing bank vaults, breeding alpacas, milking cows, cleaning professionally and laboring as a print and radio journalist. He now lives near a marijuana grove in the hills of western Maine. His column One Maniac’s Meat appears monthly in The Bollard, and details his exploits as a young sailor in the U.S. Coast Guard. He occasionally blogs at crashbarry.com and his rollicking novel Sex, Drugs and Blueberries and the complete version of Tough Island are available at Maine bookstores and libraries or via crashbarry.com or on Amazon. His latest book Marijuana Valley, Maine: A True Story will be published this fall.