Serial Sunday: The Weight of Light, Episode 2

categories: Cocktail Hour

Comments Off on Serial Sunday: The Weight of Light, Episode 2

[Episode 2 of on ongoing story that I’m making by the seat of my pants, 500 words at a time. Eventually we’ll have a category where the whole thing can be read in order, but for now, scroll down to start with Episode One if you missed it!]

The Weight of Light

Episode 2

Crumbled

Of course the incident stayed with him. The next day he left the office after the morning meeting. Found he couldn’t concentrate. From the street he called St. Vincent’s Hospital and asked about a man who’d fallen in the subway. “No such report,” the woman at the admit extension said. He asked for the EMT office and she connected him without a goodbye.

“Mr. Swallow,” the next desk said.

“Yes,” Ted replied. “How’d you know my name?”

“Oh, it comes up on the screen here with your address and, like, your college girlfriend’s astrological sign.”

“You don’t sound like you’re kidding”

“You’re calling about Mr. Allway. I was one of the guys on the steps at Columbus Circle egress 12. I’m Rick. I happen to be on desk this morning. But.”

“How is he?”

“I’m afraid he’s dead. Likely, he was dead when we arrived. Aneurysm, likely. Pronounced in the wagon. We took him straight down to the morgue at Bellevue. His wife was there before we finished the paper. Poor kid, crumbled.”

“He asked me to call her.”

“I’m not allowed to tell you her phone or her name. But you know the first name. Same last name as the deceased. A two-one-two number, which means Manhattan. His name was Richard, like mine. The prefix is two-five-five. That’s the Village. They’re on Bank Street. There are two more numbers I’m thinking of. Five-four-five-four, and twenty-nine.”

“Rick, thank you.”

“One might be a street address, one might be a phone number.”

“Okay. Got it. You’re a good man.”

“Not everyone stops,” Rick said.

“It was the decent thing to do.”

“You were his last human touch.”

“I thought of that. Often it’s you, I suspect.”

“It’s a heavy weight, Mr. Swallow.”

“Ted.”

“It’s a very heavy weight, Ted.”

#

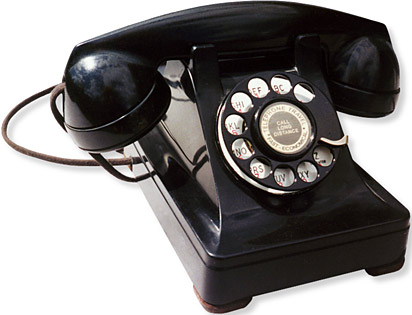

It was a very heavy weight, all right. Ted hadn’t had so much trouble picking up the phone since he’d been in high school and wanted to quit chorus. His father had said fine but made him dial Mrs. Conklin himself, and her disappointment in him was so palpable that he’d changed his mind mid-conversation, finished out the chorus season in misery, one of only three boys in the risers, and worse, the one who’d tried to quit.

It would be easier from the office. Morning would be best. For the fourth consecutive day he scanned the newspapers and Googled galore, but there was no mention of Mr. Allway, nothing he could find, anyway.

Finally, a week after then incident, he did it. Punched the numbers. The message machine at the other end picked up, one of those mechanical voices, a generic greeting. He hung up. You couldn’t leave such a message on an answering machine. After lunch he tried again, got the machine again. His first client meeting took up the afternoon and it was successful, two hundred fourteen prints for the new W hotel in Philly and a great conversation after with the artist, one he’d brought with him from Markson-Markson, ha.

That kept him busy through the afternoon, contracts and billing. At five he called Ellen Allway again. The phone rang a dozen times. A weary, wary voice: “Hello?”

###

Here’s last week’s entry:

The Weight of Light

episode one

A Heavy Weight

Ted rushed up the stairs from the A-train at Columbus Circle with the crowd, a shuffling mass of humanity heading for work, as he was. Ahead of him a man in a suit slipped and stumbled, caught himself, stood again, then fell. The crowds just coursed around him, but Ted stopped. The poor guy’s face was right on the cold cement and hardened gum and spittle.

“I’m all right,” the man said.

“You’re not,” Ted said.

“I’m not,” the man said.

“You’ve fallen.”

“Call Ellen, please,” the man said. And his eye rolled back.

“Yes,” said Ted. He cradled the man’s cheek off the cement in one hand as everyone else in the world hurried up the stairs past them, fished his phone out of his front jacket pocket with the other, placed it on the step, unlocked it with an awkward finger, then punched the right buttons: 9-1-1. He touched speaker and the ringing seemed very loud. A Hispanic voice, female, said, “What is the nature of your emergency?”

And Ted, always efficient, answered every question as the crowd from his train dwindled. The stairs were almost empty now, and two more people had stopped, a black woman in a dashiki and a subway worker with a first-aid kit. The woman murmured kindly to the victim, took over the cradling of his head. The worker, admirably prepared, admirably trained, opened the kit, prepared a syringe, gave the guy a shot right in the neck, then helped Ted turn him on his back, began a clumsy administration of CPR. The woman murmured in prayer; the worker pumped the victim’s chest; Ted held the victim’s legs up high per instructions. Very nice shoes.

Surprisingly quickly, the EMTs were there, a tall bespectacled fellow in a St. Vincent’s jacket and a short woman dressed the same, but with a bright, leafy tattoo climbing her neck. The woman took over the chest compressions from the worker as the tall EMT administered oxygen and thanked them all. Ted kept holding the guy’s feet even as the woman in the dashiki removed the beautiful shoes. A third EMT brought a stretcher down, and he and the tall fellow loaded the victim on it and carried him up the stairs while their colleague kept up her dogged work. The subway worker followed them. The black woman hugged Ted and he hugged her back, silently. She smelled of cooking. “Lord Jesus, help him,” she said. She patted Ted’s shoulders, then handed him the guy’s shoes. Probably they’d cost two thousand dollars: Ferrangamo.

The woman bustled down the steps to the squealing of a train arriving. Ted climbed out into the sunshine, carrying the shoes. The ambulance had already pulled out. No sign of the subway worker. He held the shoes and watched a long time. And then he simply walked to his new office, all the new faces, all the pleasant smiles, found his desk over the gallery floor, put the shoes in one of the empty drawers in his desk, opened yesterday’s file on his huge new I-Mac, stared at the meaningless words and images and icons a long time, found himself weeping copiously, no one to tell.

He’d have to find Ellen.