Among Western authors–those who write about the West, that is–it’s arguable that none stand above Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey. At the very least, no two writers presented such antithetical personas: Stegner, the buttoned-down professor and family man dedicated to discourse and process, vs. Cactus Ed, Stegner’s former pupil and irascible, impatient anarchist, who fought all development as despoilment.

But can you judge these books by their covers, or even by their books? Award-winning nature writer David Gessner wasn’t sure, so he lit out to the land they called home (if not always), searching for the truth beyond their iconic images. The result will appeal to fans of both authors: All the Wild That Remains is an entertaining, illuminating travelogue, as well as a thoughtful examination of the complicated men and their legacies across modern landscapes.

But can you judge these books by their covers, or even by their books? Award-winning nature writer David Gessner wasn’t sure, so he lit out to the land they called home (if not always), searching for the truth beyond their iconic images. The result will appeal to fans of both authors: All the Wild That Remains is an entertaining, illuminating travelogue, as well as a thoughtful examination of the complicated men and their legacies across modern landscapes.

Here Gessner contrasts the two giants of Western literature, starting at the top with with the most conspicuous, if superficial, difference: their chosen hairstyles. All the Wild That Remains is an April 2015 selection for Amazon.com’s Best Books of the Month in Nonfiction.

Of Canyonlands and Coiffures: Abbey and Stegner’s Contrasting (Hair)Styles

by David Gessner

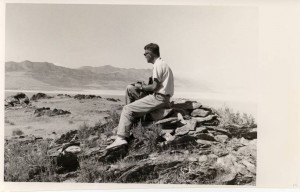

There’s more than one way to fight for the environment and more than one style. This was a point that kept being driven home during my travels through the American West for my new book, All The Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West. It was driven even deeper during my three years of researching and writing the book, as I began to learn more about the lives and work of two of our country’s greatest 20th century writer-environmentalists. I believe that Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey provide models for the rest of us, like human signposts, though at first the signs sometimes seem to be pointing in opposite directions.

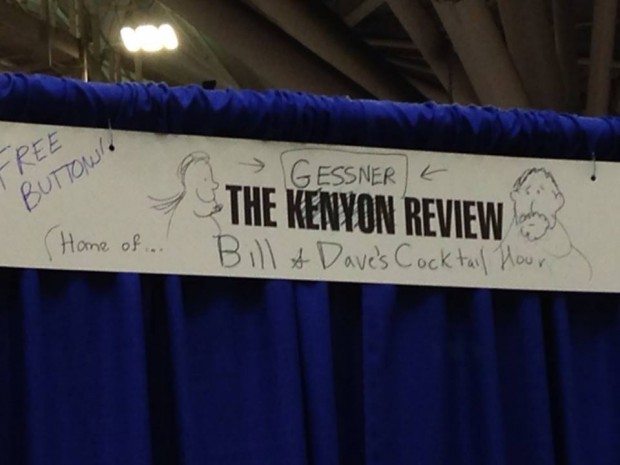

One of the fun parts of writing the book was comparing and contrasting Stegner and Abbey. I didn’t want to caricature them (except when drawing actual caricatures like the ones above) but there they were: the proper, virtuous, almost regal Stegner, on the one hand, married to the same woman for 59 years, and on the other the wild, self-proclaimed monkey-wrenching anarchist, Abbey, who had five children with five wives. It got to the point while writing the book that I felt I could write a whole chapter by simply contrasting the two men’s hairstyles:

There were plenty of other fun methods of contrasting as well. One was their different attitudes toward the river trips they took. Abbey, near the end of a ten day paddling trip on the Colorado, wondered if he could just stop and live there forever, roaming the side canyons, wandering naked, shooting deer and drinking river water, seeing no one. Stegner on a similar trip, also fantasized about an extended stay in the canyon, but with one telling addition: he thought it would be a great place to roll up his sleeves and write a book.

Work, and its deep pleasures, was always a touchstone for Stegner. Meanwhile part of the appeal of Ed Abbey, I’ve come to believe, is that he understood the lost art of lounging. Here he is in Desert Solitaire: “I was sitting out back on my 33,000 acre terrace, shoeless and shirtless, scratching my toes in the sand and sipping on a tall iced drink, watching the flow of the evening over the desert.”

Virtue, outside of the virtue of saving wild places, doesn’t have much of a role in Ed Abbey’s work, and do-gooders are frowned upon. Meanwhile sensual pleasure, which plays such a large role in Abbey’s life and writing, goes virtually unmentioned in Stegner’s.

I began to think that we read Wallace Stegner for his virtues, but we read Edward Abbey for his flaws. Stegner the sheriff, Abbey the outlaw.

I remember an essay written by the editor and essayist Rust Hills about Michel de Montaigne and Henry David Thoreau. “Montaigne is somehow marvelously humanly indolent; Thoreau had an exceptional, almost inhuman, vitality,” he wrote. “Thoreau kept in shape….” What does he mean by this? He means that Thoreau, though famous as someone who retired from the active world, worked vigorously on himself and his art, walked hard (four hours) each day, wrote in his journal, striving for a higher, better life. Montaigne in contrast, accepted his sloppy self. The song he sang was: “This is me. Take me as I am. I do.”

Abbey, of course, plays the Montaigne role here, and while Stegner may at first seem miscast in the Thoreau role, this particular aspect of Thoreau fits well. With Stegner, there is always a sense of vigor, fitness, striving to be more.

This came through in the way they fought for the planet. While Stegner’s political thinking was more sophisticated and restrained, Abbey’s words had a rare attribute: they made people act. Monkeywrenching, or environmental sabotage, has recently been lumped together with terrorism, but Abbey could make it seem glorious. After finishing a chapter or two, readers would want to join his band of merry men, fighting the despoiling of the West by cutting down billboards and pulling up surveyors’ stakes and pouring sugar into the gas tanks of bulldozers, all of this providing a rare example of true literary influence at work.

Abbey wrote from two sources: love and hate. He said as much, claiming that a writer should be, “Fueled in equal parts by anger and love.” He had fallen in love with a place and he wrote paeans to those places while cursing those who were trying to despoil what he loved.

He wouldn’t have used the word “despoil” of course. He would have chosen, as he often did, the more direct and blunt “rape.” And why not? The enemy was aggressive, rapacious, never resting. In response he had to be the same. Words were his first line of defense, maybe his last, and he piled them up like a barricade of rubble. Though he could be brutally concise, he was also a hyperbolist, and like Thoreau, varied between these two extremes. Both an embracer of excess and a blunt blurter. Either way the words seem to have been summoned directly from and in defense of the land. His is not the effort of a stylist.

If Abbey didn’t despise with such passion his would be just run of the mill curmudgeonly grumbling. In Abbey’s world Lake Mead, Lake Powell’s downstream cousin that was created by the Hoover Dam, is “a stagnant cesspool” and “a placid evaporation tank,” while the cars that tourists drive in are “upholstered mechanized wheelchairs.” He writes: “With bulldozer, earth mover, chainsaw and dynamite the international timber, mining, and beef industries are invading our public lands—bashing their way into our forests, mountains and rangelands and looting them for everything they can get away with.” “Mr. Abbey writes as a man who has taken a stand,” was how Wendell Berry once put it.

This is both instinctive and the result of a thought-out philosophy. “It is my belief that the writer, the free-lance author, should be and must be a critic of the society in which he lives,” is how Abbey begins “A Writer’s Credo.”

He continues:

“Am I saying that the writer should be–I hesitate before the horror of it–political? Yes sir, I am…..By ‘political’ I mean involvement, responsibility, commitment: the writer’s duty to speak the truth–especially unpopular truth. Especially truth that offends the powerful, the rich, the well-established, the traditional, the mythic, the sentimental.”

If Abbey was Mr. Outside, then Stegner was Mr. In.

Here is what Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt said about Stegner’s biography of John Wesley Powell:

When I first read Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, shortly after it was published in 1954, it was as though someone had thrown a rock through the window. Stegner showed us the limitations of aridity and the need for human institutions to respond in a cooperative way. He provided me in that moment with a way of thinking about the American West, the importance of finding true partnership between human beings and the land. (FN: 208 JB)

Even Ed Abbey, who may not have even liked Stegner that much, said of him: “Wallace Stegner is the only American writer who deserves the Nobel Prize.”

That these words did not come from a student trying to butter up a teacher—who could be more antithetical to wild Ed than the older, buttoned down, conservative, hippie-hater?—make them carry even more weight. Abbey admired Stegner’s work and his commitment to making art, but perhaps admired more his teacher’s commitment to fighting for the land.

At the urging of his friend, the writer Bernard DeVoto, Stegner began to write a series of environmental articles in the early ‘50s, and those articles were read by David Brower, the charismatic single-minded executive director of the Sierra Club. Brower recruited Stegner to edit a book that would describe the wonders that would be lost if a dam were built within the borders of Dinosaur. In their successful campaign to stop the dam the two men would not just help win a battle but would revolutionize the way environmental fights were waged. Until the effort to save Dinosaur there had been something upper crust and musty about the Sierra Club and the other environmental organizations, but with Dinosaur they would go from fuddy-duddys to fighters. Over the next decade great gains would be made and a new style forged: full page ads would be taken out in major papers comparing the damming and drowning of the Grand Canyon to the flooding of the Sistine Chapel, beautifully photographed books would help change our national consciousness, park land would be purchased as it hadn’t been since the days of Teddy Roosevelt, culminating with the Wilderness Act.

In 1960, Stegner published his soon-to-be-famous “Wilderness Letter,” which argued that wilderness was vital to the American soul, and that undeveloped land was deeply valuable, even when that value was not obvious and monetary. One influential reader of the letter was the new Secretary of the Interior, Stuart Udall who thought so highly of it that he read it out loud at a Sierra Club gathering in April of 1961. By then he had also read Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, and he was determined to get Stegner to come to Washington with him. Stegner was reluctant; he was a writer with work to do, not a politician, but eventually he gave in. In D.C., he worked on the beginnings of legislation that would become 1964’s ground-breaking Wilderness Bill and attended meetings with Udall, during which, according to the Secretary, Stegner was “never bashful.” The eventual bill was in fact an almost perfect practical embodiment of the “Wilderness Letter,” a massive setting aside of lands never to be developed. For Stegner it was a heady experience, and he got “an inside look at parts of the Kennedy administration during its first energetic year” as well as “a good lesson in how long ideas that on their face seemed to me self-evident and self-justifying could take to be translated into law.” He also went on a vital reconnaissance mission to Utah for Udall, scouting the land that the Secretary would eventually save as Canyonlands National Park.

But the truth is Stegner only lasted four months in Washington. At heart he was not a politician but a writer and teacher. Mary Stegner found D.C. cold and lonely, and by the beginning of the spring term they were back at Stanford. His relationship with Udall would continue, however, and he would help the politician write the early drafts of what was to become Udall’s best-selling conservation manifesto, The Silent Crisis. And for the rest of his life Stegner would keep fighting in the environmental wars despite the fact that these obligations “constantly prevented the kind of extended concentration a novel demands.” It would have been nice to have turned his back on these extra obligations, but of course, being who he was, he couldn’t.

For Stegner, who always valued results above mere theory, efficacy was a great virtue. Or maybe it is best to say that he valued real-world effectiveness along with theory, broad ideas applied to the practical earth.

Overworked as he was, Stegner’s could sometimes be a grumpy goodness. In a fascinating exchange of letters with the beat poet and environmental guru, Gary Snyder, Stegner argues for the less exotic virtues of the cultivated western mind versus the enlightened eastern one. This included the importance of doing what one should and not what one felt like. In a letter dated January 27, 1968, he wrote: “I have spent a lot of days and weeks at the desks and in the meetings that ultimately save redwoods, and I have to say that I never saw on the firing line any of the mystical drop-outs or meditators.”

He went to those meetings because it was the right thing to do. An obligation, yes, but one he valued.

“The highest thing I can think of doing is literary,” he wrote a friend. “But literature does not exist in a vacuum, or even in partial vacuum. We are neither detached nor semi-detached, but linked to the world by a million interdependencies. To deny the interdependencies, while living on the comforts and services they make possible, is adolescent when it isn’t downright dishonest.”

Which meant sitting in at those boring meetings where he saw no mystical drop-outs or meditators. And giving talks, writing articles, and even propaganda when he would have rather been immersing himself deeply in a novel. He sometimes grumbled about this, of course he did. It was extra work, yet another thing-to-do in a life full of them. But he had signed on and he wouldn’t ever really sign off. Like Major Powell, he knew the despoilers, the extractors, would never rest. You never really “won” an environmental battle, after all, just saved places that would be fought over again in the future. Since the boomers never rested he knew that meant he could do very little resting himself. Unlike many of us today, he did not take environmentalism for granted, since when he had begun to fight it barely existed. Stegner concludes his “A Capsule History of Conservation” this way:

“Environmentalism or conservation or preservation, or whatever it should be called, is not a fact, and never has been. It is a job.”

So he did his job.

As did his former student, Ed Abbey, albeit in a very different way. Though he was a very different man than his old teacher, they had common ground. For Abbey and Stegner that ground was the earth itself, a place they both loved and were willing to fight for.

Today is a doubly significant day for me. It is both the pub day for my new book about the American West and the fifth anniversary of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the pleasures of writing the book was spending a few years studying not just the work but the thinking of Wallace Stegner, and Stegner wouldn’t have wasted too much time making the connection between the drought in California and the spill in the Gulf. That they can be connected, and not just by the one-size-fits-all cudgel called climate change, seems obvious enough. Both events push us to think harder about resources and energy, not in a cliche or soft manner but in a real way, and in both cases both are deeply tied to the specific geographies of the places: one a near-desert that has long been in denial about its own aridity, and the other a near-tropical wonderland that has been long treated as a dumping ground and resource colony.

Today is a doubly significant day for me. It is both the pub day for my new book about the American West and the fifth anniversary of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the pleasures of writing the book was spending a few years studying not just the work but the thinking of Wallace Stegner, and Stegner wouldn’t have wasted too much time making the connection between the drought in California and the spill in the Gulf. That they can be connected, and not just by the one-size-fits-all cudgel called climate change, seems obvious enough. Both events push us to think harder about resources and energy, not in a cliche or soft manner but in a real way, and in both cases both are deeply tied to the specific geographies of the places: one a near-desert that has long been in denial about its own aridity, and the other a near-tropical wonderland that has been long treated as a dumping ground and resource colony.

This went up today at Amazon’s

This went up today at Amazon’s

Dear Readers,

Dear Readers,

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.