Jan 19

Mark Spitzer

categories: Cocktail Hour

Comments Off on Mark Spitzer

Mark is gone and the world is less wild, less joyous, less creative, less fun.

Mark is gone and the world is less wild, less joyous, less creative, less fun.The Mark Spitzer I met in 1991 was a whirlwind of creative energy, of wildness and wackiness, a guy who like his hero Mr. Kerouac, was if not always on the road then always on the move. In his excitement he couldn’t wait to scribble down the fervid thoughts in his head, and sometimes that meant whipping out his trusty orange felt pen and writing sentences right on his pants, sometimes right on his arms. He was the first person I met who was as obsessed with making books as I was, but he was braver than I. Until I met Mark I had been a scared perfectionist, working forever on a novel and not letting anyone, and I mean anyone, see it. Mark was the opposite. He not only blasted out inspired stories and poems and essays, he then turned around and sent them out into the world with the same near-manic energy. With that trusty orange felt pen he mailed his stuff everywhere, from the New Yorker to the Lunar Dog-Fang Journal. He was not afraid and he was awarded with publication—an idea that seemed miraculous to me back then, that someone might actually read your work!

His energy was contagious. Like the nouveau beat he was, he drove back and forth across the country in a van called the Unit, catching trash fish and later monster fish, then bunked up for a while in Shakespeare & Company in Paris, where he translated Genet and had doomed love affairs (his specialty until he at last found his great love), creating a fullness to life that combated the existential emptiness that always lurked. “You’re the guy who writes books,” he said to me when we met, though he already was that. His words had a Wizard of Oz effect on me, making me believe. We took many bong hits and drank many beers and went to Ed Dorn’s class to hear him monologue about the High West. Mark moved up to what he called The Mountain Palace in the foothills above Boulder with his Mountain Gals Nina, Melinda, and Beth, where he would make them pancakes and reach things on the upper shelves they couldn’t reach. We all became characters in his books. Nina was Sweet Nina, I was Gruff Dave. He wasn’t crazy about the idea of Gruff and Sweet intermingling, and he would sometimes growl (an actual growl) at me when I got too close to my future wife. He was right to be wary. During one of his many road trips, I moved into the Mountain Palace and turned his tiny bedroom into my office. When he came back he made camp in the cold basement where he tied a line to the light switch and turned it on and off with his fishing pole.

He wrote and he wrote and he wrote. It wasn’t just for the finished products (though there was plenty of finished product). It was a way of being. As he made books, he wove a net above oblivion. That was why the recent text that Nina posted last night is so heartbreaking. It reads in part: “It’s strange to suddenly not be planning the details of a book in my head or even on the computer or paper for the first time in my life.”

“I can’t imagine it,” I said when we spoke a few days ago. “I can’t imagine it either,” he said back.

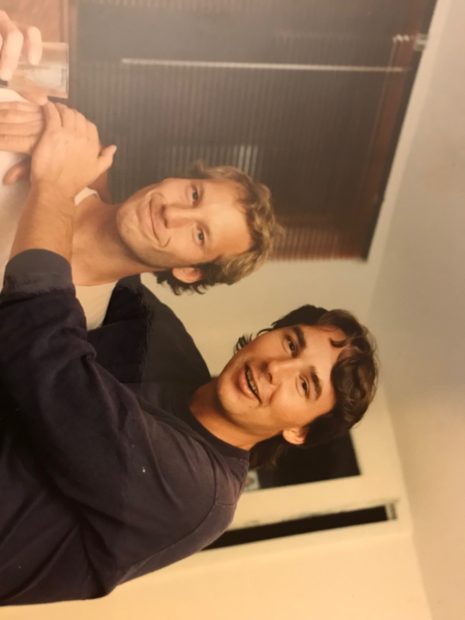

Mark belied the old idea of the asshole artist. He was obsessed but he was sweet. A wild man but a good man. When I saw him in October he was proud that he had finally gotten his hair just wildly right (see first comment below). Lea says that as late as last Saturday he was working, which doesn’t surprise me. Last week we were brainstorming about a final podcast and he was trying to set up a series of what he called deathbed readings.

Monster Fishing comes out in June at the same time my book does and I plan on reading from both books. Mark, being Mark, has two or three more books coming out after that. We both thought

Monster Fishing was a culmination and capstone of his career. The sentences are alive, spilling over with energy, electricity, occasional ecstasy, and always, raw fun. If you read it for the fishing alone you will be inspired, as well as impressed by the description of the internal ethical wrestling match that is the work of a true essayist. But the art of monster fishing is also a metaphor for a certain kind of life, Mark’s sort of life, a vital and elemental life close to the currents of nature, a life beyond the merely human, a life that is no mere trudge from birth to death, but an embrace of the wild world and all it offers.

I hate to end something heartfelt with an advertisement. But if you want to honor Mark, consider pre-ordering the book. Let’s make it a fucking bestseller. He would like that. Here’s a link: