Guest contributor: Bill Lundgren

Lundgren’s Lounge: “The Narrow Road,” by Richard Flanagan

categories: Cocktail Hour / Guest Columns / Reading Under the Influence

Comments Off on Lundgren’s Lounge: “The Narrow Road,” by Richard Flanagan

I have been a fan of Tasmanian writer Richard Flanagan ever since reading Gould’s Book of Fish (Stuart Gersen’s all-time favorite novel). Flanagan’s work might at first seem preoccupied with man’s abject cruelty to his fellows, as many of the stories take place in wretched prison settings. But if one looks more closely, there is a discernible thread weaving itself through through each narrative, examining the nature and limitations of human love and man’s capacity to endure the most dire circumstances.

Here is a passage from Flanagan’s relatively unnoticed and unremarked upon novel from 2006, The Unknown Terrorist, that captures the power of his writing:

“… The innocent heart of Jesus could never have enough of human love. He demanded it… with hardness, with madness, and had to invent hell as punishment for those who withheld their love from him. In the end he created a god who was ‘wholly love‘ in order to excuse the hopelessness and failure of human love. Jesus, who wanted love to such an extent, was clearly a madman, and had no choice when confronted with the failure of love but to seek his own death. In his understanding that love was not enough, in his acceptance of the necessity of the sacrifice of his own life to enable the future of those around him, Jesus is history’s first, but not last, example of a suicide bomber.”

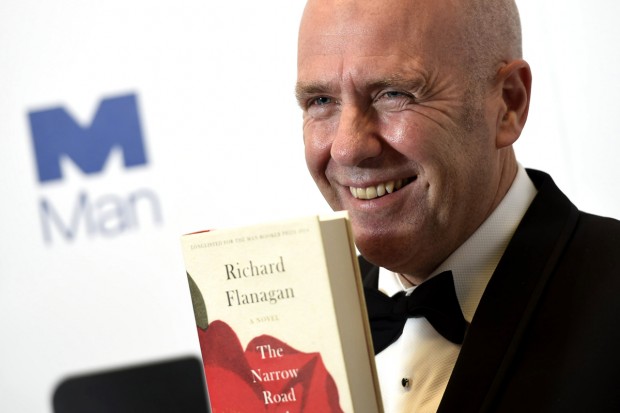

Flanagan’s most recent novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North has been universally acclaimed as a masterpiece. Winner of the Man Booker Prize, The Narrow Road tells of the life of Dorrigo Evans. The interwoven strands of that history include his experiences as the leader of a group of Australian prisoners in a brutal Japanese POW camp, his intense affair with his uncle’s wife before the war and his life after the war as a surgeon and a husband and father, who becomes, to his own bemusement, rather famous mostly it seems, for being famous.

Dorrigo meets his uncle’s wife by chance in a bookstore, only learning later of their family connection and embarking upon a passionate affair that seems inevitable and that remains alive in his memory even years after it has ended. The lovers are first separated by war, but in the war’s aftermath they seem paralyzed from resuming their affair by a curious ambivalence and perhaps suspicion of what they had once shared. In its stead Dorrigo becomes a compulsive philanderer, even as he marries and becomes a father.

But at the heart of this luminous novel is the day to day life of the prison. The Japanese are attempting to build a railroad, both as military strategy and to glorify the Emperor. As a colonel, Dorrigo is in charge of the prisoners, and in his attempts to minimize the horrific toll that the combination of lack of food and hygiene and the debilitating physical labor exacts upon his men, he discovers to his surprise that he has a natural aptitude for leadership. Flanagan’s father was a prisoner in the Burma death camp and in interviews the author has spoken of how his father’s stories from the camp had impacted his own life. The unceasing misery of the camp is leavened by the prisoners’ sense of humor and resiliency, but there are passages that are difficult to read, describing as they do man’s astonishing capacity to inflict pain upon their fellows. It is the power and eloquence of Flanagan’s writing that makes this novel important and necessary and a fitting testament to the author’s father, who died on the day that it was finished.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]