Learn to Type in Ten Days: Neck, Part III

categories: Cocktail Hour

14 comments

At some point during my nap before the football game, one of the nurses had taken the IV port out of my hand—I kept crimping the line with my thrashings and setting off an alarm. So at midnight the Queen came in and said I’d have to take my pain meds by mouth, but first I’d have to eat something. The last thing dripped into the IV had been an anti-emetic and I was feeling pretty good and actually a tiny bit hungry. My dinner had mysteriously disappeared without my ever having looked under the pressed post-consumer recycled-plastic cover, and I felt this as a loss.

The Queen brought me a little plastic cup of orange sherbet and nothing ever tasted so delicious. I wanted vanilla, too, to make a Creamsicle out of it—that’s how long it had been since I’d tasted orange sherbet, like at Friendly’s with the whole family in the wood-paneled Dodge station wagon back in Connecticut, 1965 or so. And the last time I’d had care like this—pneumonia in high school, a terrible cough, no voice. My mom got me a bell to ring when I needed something up in the hinterlands of my attic room and the first day every time I rang it someone came trotting up the stairs, one or another of my brothers and sisters, mother, father: You rang? The next day, only my mother would come, and sometimes Doug. Day after that, no one would come at all. Well, Mom, but only on her own schedule. Third day she brought me a book by someone named Ruth Ben’Ary, how to teach yourself to type in ten lessons. The idea being that if I was going to miss two weeks of school I should put the time to good use. And how clearly I remember sitting up at the desk coughing away and smoking tiny hits of hashish and coughing even more and timing myself typing exotic sentences with perfect proper hand position, every letter used, and then onto numbers and punctuation. My friend Kurt visited and we typed up profane inventions together–he brought me a pack of Kools with the idea that the menthol would be good for my throat. I’m a great blind typist to this day, and to this day don’t expect anyone to come when I ring.

So imagine my surprise when the Queen came back with my meds. I ate them and put the TV off and next thing I knew, 4:00 a.m., a young woman was hovering over me, wrapping my arm in the blood pressure cuff. “Taking your vitals,” she said.

“I would prefer you left them,” I said.

“You are funny,” she said in the same tone you’d say, Please shut-up.

My blood pressure was comically low, like 54 over 12, having been highish at check-in, back when I was still so scared.

“Nutrition will be here at 7:00,” she said.

I haven’t mentioned the leg cuffs. All this time I have these amazing leg cuffs on—they fill with air every three minutes or so, then slowly deflate, keep the blood circulation strong in your legs to prevent clots, another way to die. It’s like this robot massage, very nice, a little click as the pump comes on, and then the little motor working.

Nutrition woke me at 7:00, saying only one word: “Nutrition,” a person with no identity issues.

I noticed for the first time a pamphlet on my bedside table: Welcome to the Short Stay Unit. So, it was not the Short Story unit at all, very distressing. I was returning to reality, a strange, serious place. I checked my cell phone remembering I’d texted Drew and found I’d texted a lot of people, many of them multiple times, none of the messages as rosy as my memory of the day was, more like this morose and self-pitying message to my friend Kris: “v. sick.” Or Carlita: “not dead but close.” Very, very warm messages back, none of which had lodged in memory. And a lot about puking, back and forth with my surgery-wise brother Randy, whose last message was simple and a bit cryptic after the fact: “suppositories!”

The anesthesia was still working its way out of my system, though. I opened the breakfast: French toast and oatmeal. I don’t really think French toast should be steamed for hours after the griddle part, but wasn’t in a position to complain. And I am allergic to oats, sadly, because I love oatmeal and anything to do with oats. Gastric distress exactly four hours after consumption, is the shortest way to say what happens when I eat them, even very small amounts. So I ate the French toast: hungry. And the Queen was still in attendance, arrived with her retinue, all kinds of adjustments of my wardrobe, as apparently my balls were showing. One of her coterie brought some more sherbet, delectable with pain pills. And the Queen herself said, “You ready to leave?”

“I think so.”

“P.A. will be here later, let you go if you’re ready?”

“I can go?”

“If you’re ready. You have to be able to pee.”

Easy as that!

The P.A. (physician’s assistant, what’s that all about?) was a kindly man in glasses and clipboard who knew about Farmington from skiing up this way, but had to ask me what operation I’d had, or maybe that was a test. If so I passed, and then we talked about skiing a lot, and then about how I shouldn’t try to do it till next year, and shouldn’t work with my hands over my head and shouldn’t do things that hurt. He gave me instructions about my incision, which I promptly and thoroughly forgot. “Have you peed?” he said. “Yes,” I told him valiantly. “How much?” he said. “Like a lot,” I said, “I carried the circulation cuffs thing in the bathroom twice in the night.” “Was it pretty shy?” “Very shy, but then it came out. Not gallons.” He said, “Like a pint?” And I said, “That would mean something different in a pub.” No reaction, so I said, “Yes, like a pint.” “You’re good to go,” he said. “Get dressed.” “May I take off the cuffs?” Finally, a smile: “You don’t need the cuffs.”

I called Juliet at the hotel and she said she’d promised Elysia they’d go to Denny’s for breakfast and that they were still in jammies and weren’t in very good moods so it would take a couple of hours.

“But,” I said.

“You’ll have to stall,” she said

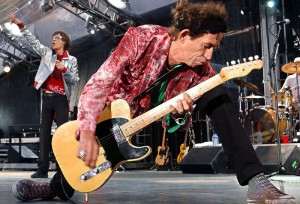

I dressed in clothes from the pink garbage bag I’d put them in, day before, and put my i-pod on and sat in the stiff arm chair, head whirling pleasantly, more Fresh Air, wonderful interview with the incredibly louche Keith Richards, fell asleep. In an unspecified while a nurse came in and took the light dressing off my incision, had a look, gave me instructions that I forgot completely except that I was to keep it uncovered, which seemed wrong.

Keith Richards dreamed the music and part of the lyrics to “Satisfaction,” he said. The guitar parts on some of their best songs are just an acoustic amped through a radio, something like that, anyway, all that distortion of the rich sound is natural, and “Under My Thumb” is not misogynistic. They played a bit of that and I remembered hearing it at the snack bar at Roton Point, a beach club my family attended, could perfectly see the breakwater there and the huge wooden structures of the place and the perfect smell of the French fries, the heat of the sun, tennis lessons futile, and a certain girl in her bikini, same girl in the abandoned ping-pong room with the neck part of the bikini untied and hanging down, and cigarettes.

I woke to Elysia and Juliet arriving. They were in the midst of a disagreement of some sort. “I can go,” I said.

“Is it covered?” Elysia said. My incision, she meant.

I pulled my collar up and then she’d come in, but didn’t want to get too close. Her experience of hospitals is her two grandmothers, who both went in and didn’t come out.

Two hours later after various perfectly charming and understandable delays the nurse’s assistant who’d attended me the day and then evening before was wheeling me out in a wheelchair amid waves of unreality, Keith Richards in scrubs, for one example. We passed the big sign for the Short Stay Unit and really, it’s very hard to make these people laugh but my attendant giggled at the Short Story Unit thing and said she couldn’t wait to tell everyone that and delivered me through a revolving door to my girls and to my car, which I wouldn’t be allowed to drive for a month or so.

It turned out that what Elysia was mad about was that I was getting all the attention. And that what Juliet needed despite Denny’s was desperately to eat. Also, Elysia wanted to listen to Fleetwood Mac, which Juliet was sick of, Juliet to Furthur bootlegs, Elysia: sick of. Full bore tussle. I was brought in as the tie breaker but voted for Mikado, and prevailed, since no one was sick of Mikado. I’d been advised to stop on the way home and stand and walk—it’s about two hours going slow. But I didn’t want to stop–I wanted to get somewhere with a bed. I sat up very straight, wearing the soft collar they’d given me for the ride, asked Elysia to tell me how it had been taking charge of Melissa’s baby. She took a moment to warm to her subject but then she talked a blue streak and I asked her many, many questions. A crying baby, what’s that like? It’s no big deal if you just can think what’s wrong. It might be the diaper, it might be he’s hungry. And so we talked for an hour to the strains of Gilbert and Sullivan, though I could only picture Keith Richards in any of the roles. Three little girls from school are we!

Halfway or so we stopped for lunch at the ghastly and overcrowded Panterra in Augusta, surprisingly good soup and even better bread, so I may revise my review at some point, but for now ghastly must stand. Hunger! That was the source of the discord! Everyone stared at my collar or didn’t look at me at all, no middle ground. You can’t flirt with soup girls in a neck brace, at least not Panterra soup girls, except one goth gal, who probably knew from incisions. My throat! Swallowing was awful, awful. I’d been warned–no way around bruising the esophogus and trachea pushing them out of the way for almost three hours. I’d quit smoking thirty years before, so there would be no Kool cigarettes, and no hashish to soothe me. Food, though, and everyone cheered up; in fact the girls giggled and sang the rest of the way home, shadows in the snow like the stripes of zebras and flashes of light on my eyelids and sleep haunting me.

My road is pretty normal for western Maine but would be arrested for first-degree felonious assault anyplace else, just a loose assemblage of asphalt pieces and ice and chasms and axle parts, but I wouldn’t have to traverse it again for at least two weeks. Home was where the heart was. I staggered in and straight upstairs and into bed and blessed sleep to Terry Gross talking about terrorism and then about True Grit, all crazily interwoven with my dreams of latticework wildlife. Later, I choked a soft dinner down and ate my next hit of oxycodone, then some more at bedtime, the full dose, baby, the anesthesia still working its way through my system, and watched TV, or really stared at it in shock, could make nothing of what was on, people saying things, doing things, totally bizarre behavior regardless of channel. I panicked that what I’d expected was not available: gentle laughs. So to bed, my familiar pillow at least, incision unwrapped, sudden frenzied sleep, sudden awake: a dream that the world had become abstract, that everything was abstraction, and in the extrapolation of the idea of library were only the ideas of books, a lot of actual labels, interpolations, very hard to explain the horror of this, like working in an English department, but woke and couldn’t shake the dream, my whole house an abstraction, staggered downstairs into the “bathroom” and could not pee and the dream was still with “me”—I was dreaming awake. I paced the “house” an “hour,” finally crashed my way back up the “stairs” to “bed,” slept till noon and Keith Richards.

Bill’s Vitals . . .

Some long ago spring I was lying on a couch, green and white striped, in a suburb of Princeton, New Jersey, reading an article in Harper’s about renovating a house but also a life. At the time I was painting and house-sitting, jobs a friend’s parents had offered more out of pity than need, I think. They were doing me a favor more than I them. But I was glad to install and paint their crown molding and at night take nips out of the liquor cabinet and not think about the fact that I was several years out of college, had started and halted a graduate program, still at thome, and wasn’t too sure about the next direction. I had liked working with my hands, had worked summers installing kitchen cabinets, doing light carpentry, and painting houses. The problem with reading graduate literary theory was that there was no finished product, what we used to call the “beautification process”—stand back and look at what you’ve done–though sometimes we left houses more soiled than when we started. And here was someone who also followed around dad on weekends, took Woods I and II in addition to the college prep courses (my group made weapons in the varnish room more than drug paraphernalia, but it was the Reagan 80s).

I went back to grad school too, started reading more nature writing, kept me grounded as theory might not have, more grad school, a dissertation and book on literary cartographers and a teaching job that involved teaching creative nonfiction though I had never done that (you wrote about nature writing and that’s creative nonfiction no?). And I was starting to do my own essay and creative nonfiction writing now and the book I chose was Writing Life Stories by some guy named Roorbach and I enjoyed teaching it, the students liked it too, liked the laid backedness, the sense of humor, something in the voice we responded to. And I experienced something like a déjà vu way back to that striped green couch even before I turned to Appendix A, “Into Woods,” reprinted from Harper’s April 1993.

A few years ago I wrote a book on kids and nature, A Natural Sense of Wonder: Connecting Kids and Nature through the Seasons, a collection of essays where I try to follow in the footsteps of Rachel Carson, scooped some by Richard Louv, but great review in Orion by Brian Doyle (in case readers of the Cocktail Hour are interested . . . ). I thanked Bill in the acknowledgements for “getting me back into woods” and reading these posts has reminded me why: it wasn’t necessarily concrete writerly advice in WLS but more his generous spirit and all-around good-natured outlook and voice. I read a column of his and he makes me feel good and laught ( even at the the corny jokes ;-).

The editor at U of Georgia Press has asked for a follow-up book on older kids and nature but like Dave, I’m sick of nature, or sick of kids and nature, or just sick of my last book (and reluctant to make my kids guinea pigs again—and who really understands teenagers anyway?). Have been trying my hand at a fiction story that young adults might actually read, a la Nina’s excellent Every Little Thing in the World, so if you have a fiction version of WLS Bill get it out there . . . (though we already have Big Bend and The Smallest Color).

Anyway, just wanted to say thanks and keep at it and get better soon.

P.S. Joyce Carol Oates lived next door to that house, but I never saw her come or go. Maybe that’s why she’s so prolific.

Thank you for your generous humor and sharing: I hope that the craziness will abate and provide you long skeins of fruitful material.

Sending you healing wishes from Homer, and I second Erin’s urging that you come back up here!

cheers,

Ela

Let’s be honest – what a rare pleasure it is, in perfect safety and good health, to read about the suffering of others! Thanks for providing that pleasure so generously. Another great ride, from sherbet to a world gone abstract and terrifying, with many points of interest along the way. Wonderful stuff – so glad you learned to type!

Funny, but the typing may be part of the problem with my neck… But soon enough (cf reply to John Jacks below) my suffering will be over…

Where are parts one and two? No fighting, I can’t cope with it right now! Unless it is over democracy!

Oh, you just scroll down… Sorry that’s not clear–things in Bill and Dave’s topsy turvy world get posted then pushed down by newer posts…

The story so far does what I like a story to do. It’s emotionally compelling and intimately personal. The humor raises the entertainment bar on what is otherwise a tragically too commonplace traumatic situation. Yet honest, self-sacrficing humor embiggens noble spirits.

If there’s a shortcoming, it’s that the practical outcome of the surgery itself was given up front. To me, that currently stands out as the surface main dramatic complication.

Athough, as the main dramatic question, what will happen in the end, has yet to be finalized, I’m prepped for a character transformation. It’s kind of foreshadowed in the opening installment subtext; recognition of aging changes are invoked.

At the least, what that unanswered profound self-realized recognition will be compels me to read on. I see in my crystal ball resistance to change and coming to a reluctant accommodation with a new normal physical and emotional equilibrium. I’m eager for the payoff.

Apparently, the most common outcome of this operation is you are 19 again and stoked!

My knee-jerk nurture nature thought to reply, Right. Uh-huh. A man westing toward sixty with a spinal fusion and degenerative disc disease and thinks he’s a sapling 19 again is a catastrophe in the making. But I expect discharge instructions said to maintain a positive attitude. Good on you.

And a catastrophe in the offing leaves the final outcome in doubt until the bitter end of a rope. Aristotle and Freytag name the final change-compelling crisis of a tragedy the catastrophe. (Many writers, and readers, mis-take a final crisis scene for a climax scene.)

I’m okay that you might suffer for your artistic temperment, and for your audience’s benefit for the sake of tension’s empathy and suspense leave us, at least me, still doubtful of your final outcome.

My final outcome is assured… we just don’t yet know the date… I’m hoping for 2053…

Finally caught up with these posts this morning, Bill, watching the snow pour out of the sky, just me and Wyatt awake. Kept putting him off with semi-dangerous objects (pencil, empty baby food jar) so that I could read straight through. Really great stuff. Sorry about the suffering part, though. We’re thinking of you over here in Temple.

It’s great. A memoir and remembrances while in the midst of post op pain and medication and everything. I think driving home for two hours and stopping for lunch was hard for you having just had surgery on your neck. And the dreams are probably something to do with the oxycodone. I think they should have kept you another day. Anyway you are home safe and sound now and recuperating. I’m sorry you had to go through that. And the humor always helps get us through the bad times. I liked it when the nurse had to rearrange your clothes. Glad you are back to the writing. Get well soon, Bill!

Ah no, Dave, you are not the only one reading the blog at this point, and you’re damn straight that Bill has made illness much funnier than I’ve ever thought it might be. So, next time I’m in physical distress, I’m going to try to remember to find the lightness instead of concentrating on the dark. I hope that you get to AWP safely and happily. I’m not going to make it from Alaska this year – but I hope next. And Bill, get better soon and come back to Kachemak Bay.

Dude,

Your illness is much funnier than mine. I laughed a lot at this. It could be that only you and me are reading this blog at this point., but that’s okay. It’s getting us to write a lot.

I talked to a colleague who has some good nerve pain advice. I’ll call you from the road tomorrow… with the storm I may be the only writer at AWP. Your pal, Dave