Great Pick-Up Lines

categories: Cocktail Hour / Reading Under the Influence

8 comments

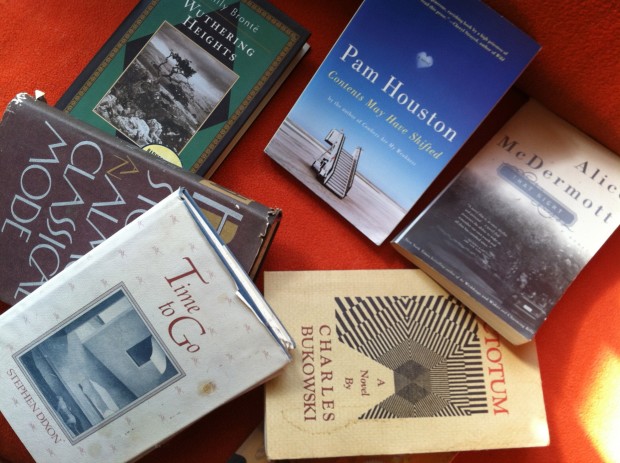

Of course I’m interested in opening lines. Mine come first as I write maybe about half the time. Many come from later paragraphs in an early draft–I’m a big cutter of early pages. The rest get written in the revision, occasionally, as with Life Among Giants, are among the very last words added. Sometimes when starting new work I go through my bookshelves randomly and read first lines, first paragraphs. Some writers–some books I should say–start with a place. Many (especially contemporary) with character. More and more, in an impatient age, writers start with plot. The old-timers started with voice and language, often philosophy, knowing we had nothing better to do than listen. The project this morning is to close my eyes and randomly pick seven titles from the fiction section of my over-packed shelves, with the rule that I have to use whatever books come into my hands. Anything I violently don’t want to use for this post must go to the thrift shop (I now have a thrift-shop box on the porch–and like Samuel Pepys, vow that one book must go out for every book that comes in!). As it happens, no thrift-shop books emerged (I’ve been assiduously culling), far from it. As it happens, some of the books are collections of stories, so the line you’ll hear is from a story rather than a novel, very different game.

Okay, seven first lines:

1. “The notice informed them that it was a temporary matter: for five days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at eight p.m.” (Jhumpa Lahiri: Interpreter of Maladies, a novel)

This is plot, that is, a disruption in the normal order that leads to story.

2. “Each year when spring comes I do a lot of handyman work for the row houses that line Wilmin Park Drive on the 2900 to 3300 blocks.” (Stephen Dixon: “The Bench,” from Time to Go, stories.)

Definitely a start from place, with a strong dose of voice and character. And you can feel the story coming, like weather. Dixon is the most energetic story teller ever, books full of very short pieces, great excitement in the quotidian.

3. “Marcus Weill has said he is chiefly concerned with virtue and death in the movies he makes, but the truth is that his usual theme is that we are not capable of much virtue because we are afraid of death.” (Harold Brodkey: “The Abundant Dreamer” (great title) from Stories in an Almost Classical Mode)

Harold Brodkey, larger than life even when you were with him (he taught for a week as a visitor at my MFA program), reads as a modern-day Proust. Anyway, he we start with character, also voice (which is also character), and a strong dollop of philosophy. No plot in sight here, though a story is emerging already.

4. “1801–I have just returned from a visit to my landlord–the solitary neighbour that I shall be troubled with.” (Emily Bronte: Wuthering Heights: a novel, of course)

Voice–first person is always voice, as in the Dixon. But character not far behind. And plot implied, the status quo interrupted in some way we just begin to fathom. And trouble ahead. A story well launched, I would say!

5. “I arrived in New Orleans in the rain at 5 o’clock in the morning. I sat around in the bus station for a while but the people depressed me so I took my suitcase and went out in the rain and began walking. I didn’t know where the rooming houses were, where the poor section was.” (Charles Bukowski: Factotum, a novel)

I cheated and gave the whole first paragraph, just to enjoy that voice, whoa. Character, yes, but plot as well, a story well launched yet again. It’s the a-stranger-comes-to-town plot, but the stranger is the protagonist.

6. “That night when he came to claim her, he stood on the short lawn before her house, his knees bent, his fists driven into his thighs, and bellowed her name with such passion that even the friends who surrounded him, who had come to support him, to drag her from the house, to murder her family if they had to, let the chains they carried go limp in their hands.” (Alice McDermott: That Night, a novel.)

Shades of Faulkner! The voice here is a narrative voice rather than that of a character (the free indirect style not yet established, though it will come, so we’re hearing the presence of a writer). But there is a character, even characters, and they are not overwhelmed by the very strong infusion of plot. Chains? Wow.

7. “We are two hours out of Sydney when the pilot’s voice comes of the PA system. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he begins, “I’m sorry to tell you this, but our instruments up here are indicating fuel system failure.” (Pam Houston, Contents May Have Shifted, a novel)

Plot, of course, but only minor plot, in that we know the fuel thing is going to work out, since the narrator is still talking and this isn’t The Lovely Bones. Pam Houston is a friend of mine, but I still think I can credibly say that Contents May Have Shifted is a work of genius, like no novel I’ve ever tasted, maybe a slight flavor of Mary Robison. It is structured in short, numbered and titled sections that aren’t stories, and that tie in with Pam’s real life, we readers suspect, especially as the narrator’s name is Pam Houston. It’s an all-of-the-above novel, right down to the philosophy. But you have to start someplace. And this book gives me a chance to talk about structure. Rare, but at times, that’s where we must start.

[Bill Roorbach likes to ski in the woods although it has caused him a lot of injuries over the years. The latest is a sore elbow, but he will put on a brace and go out anyway, right now. Forthcoming is much worse, he has a feeling. He always brings his phone in case he has to call 9-1-1, though he likes to think a friend would come get him in a pinch.]

“Of course I’m interested in opening lines.” Bill Roorbach: Great Pick-Up Lines (essay).

Started with voice here, whoa. A reply to a question we never asked that makes us think we should’ve asked it. Nay, maybe we shouldn’t have because the answer was so obvious. Implies that a true correspondence is taking place, further guaranteeing our attention. Very effective.

#6 was my favorite. Holy crap. It’s like Streetcar times 10!

Beel — Nice. I have a few thoughts to add about that “1801” — kinda slips right by you but it turns out to be very important. This book, and Emily even more than her sisters, were both considered rather savage pieces of work, grotesques with little artistic plan or vision. There is a wildness to the book certainly — and unlike every other English novel of the Victorian period the tale is kept completely separated from society, its expectations, and the constant spur of money. So for sixty years or more Wuthering Heights was viewed as a very unschooled, rough and inartistic bit of remarkable writing. Then in 1926, I think it was, a writer named Charles Percy Sanger published an essay in a pamphlet printed by The Hogarth Press, ie, by Leonard Woolf, Vifginia’s husband (I don’t think Virginia was dealing the press at this period but this could be a senile misremembering on my part). In this piece (which is really well written and even exciting, and can be found here — http://wuthering-heights.co.uk/sanger.htm ) Sanger demonstrates that the novel is in fact an intricately planned and meticulously executed story in which, by paying close attention to a complex narrative structure in which the bulk of it is told to the teller by someone who often had to told herself of things she did not witness, you can actually determine the month and year of every single event in the novel, even though the date only appears three times: 1801 at the beginning of chapter 1, 1802 in chapter two, and one passing reference by Nellie to a year twenty some odd annums past. Sanger did this fantastic analysis because it struck him that starting the book with the year was peculiar and intersting and must have some purpose. It’s a great and lively piece of criticism.

Further to this I would also say that the particular year she chose (any would have done the trick, the pattern would work regardless) –1801 — is a symbolic bit of signage unmistakable to readers of the mid-19th century. It screams Napolean — indeed, after the revolutions of 1848, it screamed that name even louder, and in that period the book was composed. And who is Heathcliff? Dark, a foundling, with terribly destructive passions and a ruthless design on all the property in sight. A book whose world appears to exist more separate than any other from the larger forces of society and history presents, in fact, a replica of those forces at play. And you can find it all in that “1801”.

You finished traveling around being famous?

xo

Beence

I love Wuthering Heights, so I had to take a peek at Sanger. Sanger is going to need another peek–wow–lots of interesting information. So glad to have the timeline. Thanks for the outline and Sanger!

You know, Vince, I typed that 1801 in as I was preparing this post and really lingered over it, that it was just a year, and not a specific date. And I was going to say something about that and forgot, but I wasn’t going to say what I’ll say now, given what you’ve pointed out: another starting place for fiction is era. And that can be hard to invoke. We think in decades, the 60s, the 70s, the 80s, and they are different in meaningful ways. But history thinks in centuries and millennia. I’ll bet 6000 BCE was really different from 6010 BCE. Just the hairstyles alone. Anyway, thanks, this is terrific.

Bill — I think it was the Dekkree of 6006BC that dictated all the cave boys and cave girls had to cover their genitals during the day and through supper in the evenings. Boy did that lead to a lot of changes. Next thing you know certain unsavory cave painters were doing up-skirts (up-skins, in those days) for extra mammoth meat. Then came the Internet.

War and Peace is also set in the Napoleanic era, a bit later than ’01 if I remember rightly.

Wonderful, and so instructive. And book management advice to boot.

Iain Banks Crow Road : It was the day my grandmother exploded

Masterly!

Bill, I love this!

What a great reminder of all the literary content writers manage in very short spaces. A reminder, too, of the difficult task a writer has in fulfilling the promises made in these openings–the promise to the reader that this is going to be REALLY good, and the promise to the subject matter to get it right, to nail it. Words are such a big commitment. There is so much possibility. I find all of this intimidating and then exciting when I like what I put down.