Getting Outside Saturday: Remembering a Couple of Fine Ol’ Dogs

categories: Cocktail Hour / Getting Outside

3 comments

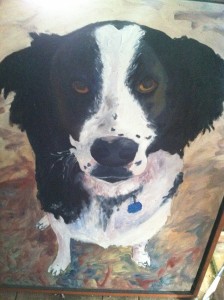

One of the great pleasures of writing is the way incidentals are captured. In my collection Into Woodsthere are glimpses throughout the essays of my late great dogs Desi and Wally, who were mutts, no better than that, though Desi had pretensions. We’d take them to the city and because they were both black and white people would ask the breed. We invented one: Muzzman Terriers. Because one of Desi’s thousand nicknames was Muzzman. One woman, hearing that, exclaimed, “Oh, I ADORE Muzzman Terriers!” Anyway, poking through Into Woods I found this passage about the fellas, who died within a couple of months of one another in 2006, Desmond at 15, Wally at 13. Desmond was the prince, Wally his loyal footman, and they couldn’t live without one another. After Desi died, limping off into the winter forest never to be seen

again, Wally would stand at the back door at night woofing: Desi wasn’t in yet! And he moped, declined. I believe the big boy died of a broken heart. We still have Wally’s ashes on top of the fridge, let them stand for all beloved animals! I still call the new dog Wally more often than I call her Baila. New means we’ve only had her six years.

Well, and here’s a passage from Into Woods (published 2001 by Notre Dame Press):

In Maine every morning we used to take the boys for a walk, what we call the circuit, down through the woods to the Temple Stream, and often through the stream in bare feet to the fields across the way, shoes back on, then up the hemlock hill and cross the stream again, hike back around on the various twitch roads and deer paths in a grand loop, every day.

Desi and Wally would leap through the tall grasses like savanna animals, or even stop and graze like cows, in fact look like little cows, black and white both of them, border collie crosses, our little herd of Holsteins.

One hot August morning Juliet and the doggies and I varied it a little and instead of crossing to the far pasture walked in the Temple Stream, old sneakers splashing in the current, the two of us people wading along maybe knee deep—oops, crotch deep, bellybutton! Shit! Cold!—on the sandy or rocky bottom in clear bright water with the dogs splashing or swimming strongly ahead or leaping up the steep banks into the revolution-era pasture our neighbor has put into conservation.

So I’m wet up to the chest, the dogs are soaked, Juliet’s laughing at me, but stumbles in the middle of her laugh and falls in herself. And up and splashing at me and we’re dissolved in laughter and the dogs come to see and prance on the sand bar in an ecstasy of being with their people.

Wally trots off and Juliet and I aren’t watching what he’s doing, but wringing our shirts, glad it’s hot as hell that day. Suddenly, a duck comes flailing at us, just off the water, and here comes Wally following at a gallop, then Desi after Wally. Juliet yells and of course Desi-the-Well-Trained stops, but Wally, trained entirely by Desi (he’s a dog’s dog, that one), keeps going, and the Duck seems injured, and immediately I think, well, Wally has hurt this bird.

I scrabble up the deep intervale bank—it’s seven feet high right there—and into the field, expecting to see carnage, feathers flying, but what I see is the field. Wally is out of sight in the tall grasses. Far away, a good, long Wally-sprint away, hundreds and hundreds of yards, I see the duck flying beautifully up out of the little patch of trees that surround a cow-watering hole there. Then I know what’s happened—the bird was faking injury to draw the dog off her nest. This is confirmed when she flies back into the stream cut where Juliet and Desi still stand, flies in low, lands on the water noisily. I slide back down the bank, just as noisily. The duck flies at Juliet, low, flies past her, wings braked hard. Well, that’s it for Desi. He’s off like an Olympic swimmer exploding from the blocks, off and around the bend, out of sight behind the slow-flying duck.

So now both of the fellows are long gone, decoyed one to the middle of the old pasture, the other straight downstream, both hundreds of yards away from the nest implied by all this.

Juliet and I continue our walk, soaked, wading upstream. “Decoy!” I pant. “She decoyed the dogs!”

“The dogs are dumb,” Juliet says. Of course she doesn’t mean this. Our dogs are fission scientists, and Juliet knows it. She means I’m dumb.

As we come abreast of the spot where Wally drew the duck out of the alders, mama duck comes back, low on the water, buzzes us from behind, rises up over our heads, flops down on the water in front of us, begins to thrash.

“She’s hurt!” Juliet cries.

But the duck is not hurt. She crashes her way upstream, flailing one wing piteously, speed slower than for the dogs, adjusted for bipeds. But Juliet and I just stand there. We’re ruining the duck’s ancient strategy, not chasing her, just standing still, too near her nest.

Wally has heard the commotion, and he’s back, takes the bait. The duck—it’s a black duck—adjusts her speed, rounds the upstream bend and out of sight, Wally momentarily behind. But then Wally has a brainstorm, wheels in the water and splashes back to the overgrown bank where the nest must be. I call him off a low opening in the raggedy thicket of drooping streamside alders, where he snuffles, excited as I am, and begins to push his way in. But finally he heeds (I have to growl at him to achieve this) and he splashes disconsolately toward us.

Behind him, the male of the duck pair emerges from the alders, silently, and swims at us, beak agape, now quacking mockingly.

He turns sharply downstream, turns his left wing out, and more or less walks on the water, dragging that perfectly healthy wing, a Matador gracefully pulling that bull-in-a-china-shop Wally downstream and off the nest. Desi’s back, now, too, and our two proud pack members race downstream sticking to the sandbars till they are forced to swim, then swim. The duck eases into braked flight just above their heads, disappears around the downstream bend. The frantic dogs follow, and out of sight.

Juliet and I take the tractor ford and leave the stream, continue on the circuit, more or less trot away from the site of the hidden nest, knowing the dogs will race to catch up with us and forget the ducklings that must be in there (in the coming weeks without the dogs I’ll get to count: nine ducklings, then eight, then seven, week by week, holding then at seven till they’re big enough to fly).

I look to the sky and there are the two adult ducks, reunited, flying tandem in a tight, low circle overhead. They swoop in, finally, and land where we dogs and people had been standing, paddle in circles silently checking their success, then duck into the alders. So to speak. The stream flows on, flows as if nothing had ever happened between ducks and dogs.

And here they come, Desi first, Wally behind, full speed over the sand bars, leaping and splashing, ears flying, galloping right past the hidden ducks, heedless, not even looking that direction: our boys! They always maraud in the direction we’re headed. We do our best to protect the wild from what’s wild in them, usually leave them home. But the wild has its own wiles, it does, and every duck his day.

I remember them fondly from Temple Stream, do I not?

Dogs obviously have emotions—why we love them—and can suffer from depression. Our new dog, a six year old pound-rescue terrier mix, almost ruined my retreat to Florida last January because she got so depressed when my wife left to return to Ohio. For two weeks Belle moped, wouldn’t play with her toys, barely ate. I could see what was going on, could almost hear her thinking—”The old woman’s gone, I’ve just got this old guy now, and we’ve left our home for good”—but could not explain. I was relieved when I drove back to Ohio with her. Belle suffers from separation anxiety and a lack of certitude in us and whatever environs we take her to. Previous dogs we raised went along for the ride, didn’t get too upset when people disappeared for a while . . .

Yes, Desi and Wally are a big part of Temple Stream the book. Desi was so smart and so emotional. He raised Wally to be more of a dog’s dog. We got him in Montana at the shelter–half Boston terrier, half Border collie. And when we moved to Maine, he was happy in the car the first few days. Last day (of four) he just refused to get back in the car, stood there drooping. Wally, on the other hand (Border colllie on one side, Basset Hound-English setter on the other, whoa), drove.

Oh boy, that was a nice Saturday morning opener! I was drawn in by the photo, truth be known. Can almost smell Desi’s sweet muzzle by that photo. All in all, a beauty; thanks.