Guest contributor: Michael McBride

Getting Outside Saturday: Flying in Alaska

categories: Cocktail Hour / Getting Outside

Comments Off on Getting Outside Saturday: Flying in Alaska

The throttle moves smoothly forward with the pressure from my left hand, as my right hand pulls the control stick back between my legs as far as it will go. The engine roars like a startled lion as it advances to twenty-three hundred rpm, and the floatplane lunges forward across the still surface of the remote mountain lake.

Ben-Hur must have felt just like this when he sent the tip of his long black whip whistling between the ears of his trembling stallions. With that sharp crack, they are off in a lunge that pushed him backward in the chariot, just as I am pushed into the survival suit that fills the backrest of my seat.

My winged chariot charges forward in a fury of white spray. The Piper seems ready to challenge the whole world. In a moment, my own 150 lunging stallions, my 150-horsepower Lycoming, fired with 80/87 octane fuel aided by miracles of steel, chrome, and aluminium, is transformed to a waterborne thing of tight fabric, bent tubing, and Plexiglas. In far less than the length of the chariot course, I have been carried high aloft by a fabulous creature that was born to be in the air. With the trailing edge of the horizontal stabilizer held slightly up, the airspeed indicator is steady at fifty-six miles per hour. The angle of inclination teeters at about forty-five degrees. In the space of just sixty seconds we are hundreds of feet in the air. Revealed now to our privileged eyes is a festival of the gods: mountains and glaciers, lakes and streams, and waterfalls beyond all counting. There is not a living soul for miles in any direction as we survey this grandiosity with the eye of a hawk. There is that same sense of bewilderment that smote us the first time we saw this wild lake we call Loonsong.

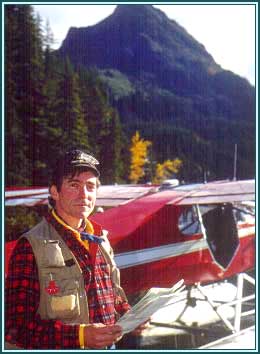

There is a powerful magnet that draws men and women in Alaska into the air and out over some of the world’s last remaining truly wild country. Stretching as it does from east to west the distance from San Francisco to New York City, with only a few squiggled lines of highway in all that vastness, flying is clearly the only way to have a hands-on grasp of the enormity and diversity of The Last Frontier.

Having your hands on the controls of your own aircraft offers a set of pleasures that are hard to describe. I am disinclined to simply call it “fun,” because this word implies a carefree attitude. The pilot must always be alert, and in the words of an experienced bush pilot who trained me, “You must always be out in front of the airplane, not just in the seat. Out in front means anticipating, thinking ahead; not reacting. You always want to know where you would land if the engine quit. You always want to be well prepared for what happens next.”

My son and daughter love to fly with me on camping, hiking, climbing, and berry-picking trips. Their appreciation recently found expression when they offered to buy a small single collapsible kayak for my birthday. An aircraft can land a person in wild country with a fishing rod, shotgun or rifle, berry bucket, or camera like nothing else can do. Add diving equipment, scientific collecting or sampling materials, or my collapsible kayak, and the geographic range for these aircraft-facilitated pursuits expands exponentially.

Owning and operating a floatplane for use in bush Alaska presents as many opportunities as challenges, as many advantages as liabilities. Entry into this small club is often limited by money, for it is not an inexpensive pursuit. Funding is often the limiting factor even if, as we do, you use the aircraft as a tool performing a function for business. If the funding hurdle can be overcome, then specialized skills must be acquired and kept finely tuned, which means flying regularly year after year. Even if you are not a licensed mechanic, there are time requirements for maintenance and upkeep, all of which adds up to a serious commitment at many levels. I stayed out of the cockpit for several years during the full-speed-ahead development of the lodge. I realized that I had too many balls in the air, too many distractions, to be able to fly safely. Leaving the ground, whether on a stepladder in the kitchen or on an extension ladder to a rooftop, implies that you might fall down and hurt yourself. Falling down when flying in bush Alaska as often as not means falling down where few people are close at hand to help you get up again. If you hurt yourself out there, you have a problem.

The bush pilots’ fraternity that I hoped to join in 1966 as a young bachelor new to Alaska was equivalent to that of the Wild West cowboys. In Alaska, the fame of the pilots matched that of John Fremont and Bill Cody. Pilots Don Sheldon and Bob Reeve had books written about them, as did a dozen other Alaskans who flew beyond the ends of the few roads. Even before meeting some of these Alaskan legends, my head had been filled with the stories of Saint-Exupéry in France and over the Andes, Beryl Markham in Africa, and the Lindberghs flying the Siberian coast. Each of them spoke to me across the miles and years about a life of adventurous flying in frontier situations. I was keen as mustard to follow in their prop wash.

[At this link http://alaskawildernesslodge.com/loonsong.htm the reader will find himself/herself in the back seat of my floatplane (the video is at the bottom of the page]

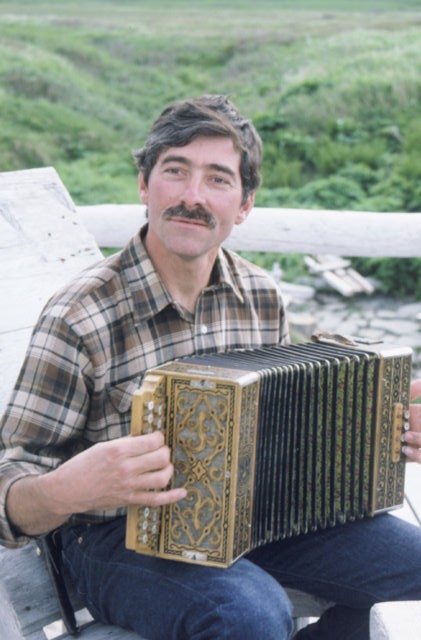

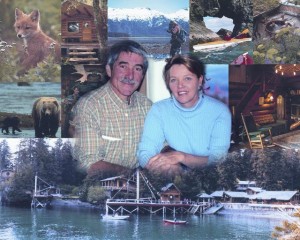

Michael McBride is a world traveler and adventurer who runs the Kachemak Bay Wilderness Lodge in Poot Bay, Alaska, with his wife Diane McBride. His new book is