From Blog to Book

categories: Cocktail Hour

7 comments

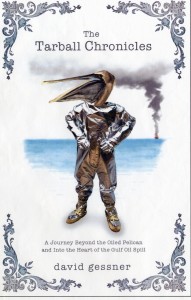

Next Monday The Tarball Chronicles comes out. The book represents my personal landspeed record from inception to publication. I went down to the Gulf to report, but also with an eye toward a book, in July of 2010, and now it is being published in September of 2011, about fourteen months later. As well as being written fast, there was something else unique for me about it. This was a book born of a blog. This blog specifically. That’s why I thank each and every one of you (true, I do this as a group) in the book’s acknowledgements. Unlike my earlier books, which were created in solitude, this one was the product of a community. And I hope the readers of this blog feel some ownership for the resulting book. Not so you run out and buy it, but because it’s true. This is the soil the thing grew out of.

Next Monday The Tarball Chronicles comes out. The book represents my personal landspeed record from inception to publication. I went down to the Gulf to report, but also with an eye toward a book, in July of 2010, and now it is being published in September of 2011, about fourteen months later. As well as being written fast, there was something else unique for me about it. This was a book born of a blog. This blog specifically. That’s why I thank each and every one of you (true, I do this as a group) in the book’s acknowledgements. Unlike my earlier books, which were created in solitude, this one was the product of a community. And I hope the readers of this blog feel some ownership for the resulting book. Not so you run out and buy it, but because it’s true. This is the soil the thing grew out of.

At first, a few years back, I had the usual tssk-tssk fuddy-duddy reaction to “blogging.” What changed this for me? I think seeing my former students, many of them my most talented students, find in blogging an outlet for their abilities. Speed of publication was appealing and also there was this: it looked kind of neat. Anyway, Bill and I started this one up in April 2010, around the time millions of gallons of oil started gushing into the Gulf. One reason I went to the Gulf was because I was pissed off about what was happening there, but there were other factors involved too. I had just had a book proposal rejected by the douchebags in New York, one I had been working on for four years–about walking around the country’s entire coast, from Maine to Alaska and bringing all sorts of coastal issues to light. And so I headed to the Gulf, in part, as my rebound project, and, lo and behold, found that many of the coastal issues I had already been studying came into play during the spill. It was as if I had been training for something and didn’t know what I was training for until I got there.

What struck me when I arrived in the Gulf was the sheer strangeness of the place, the feeling that I was in an occupied country, and the sense that this time we had really done it, that we had really shat our national bed. My posts were my way of trying to communicate that strangeness to folks back home–to you guys really–and to tell the story in my own words instead of sitting on the lap of the national media and nodding as storytellers like Anderson Cooper (my close personal friend) jabbered on. I wrote the posts on the run, usually in the very early morning, before heading off for the day’s adventure of flying in a copter out to the rig, racing over the water in the Cousteau pontoon boat, or spending a night in a fish camp. This meant that they were written fast, in a kind of journalistic shorthand, and I think that for a lot of us this will be one of the ways that blogging impacts the writing we both do and read. When you have no choice, or when you are up against it, you cut to the chase.

My first desire, when I got home from the Gulf and set to turning these posts, and my many journal notes and microcassettes into a book, was to try and preserve all the bluntness and immediacy. Had I had my own way the book would have come out even faster and would have been a kind of collection of immediate moments, with the main goal of trying to put readers down in the strange Heart-of-Darkness world of the Gulf. But that’s what editors are for, and I had a good one in Patrick Thomas of Milkweed, who pushed me to think more deeply about my greater ambitions for the book, and suggested that I could retain the immediacy while also thinking about larger connections. I am very grateful for these nudgings, and think they made the book better, and less blog-like. In other words, even though we were under time pressure, I tried to do what you always do when you truly settle down to write a book: you chew it over, you gestate, you re-conceive. “Every great effort is second born,” said Walter Jackson Bate (or was it Johnson?) “First thought best thought” might have worked for Jack K. But not for most of us.

“You spit blood for this book,” my editor wrote me not long ago. I don’t think that was an exaggeration. To get it together in a year, to have it be more than just an ambulance-chaser type of book, was the hardest thing I ever did as a writer. At first I hoped to get it out by the anniversary of the spill, but that proved impossible. And I’m glad for it. This gave me a few more months to try and go deeper, to make the thing third born.

And so, after months of hawking my My Green Manifesto wares, I turn my mind back to the Gulf. Next Monday I fly to Mobile and next Tuesday read in New Orleans. Though it has been stressful to spend the summer waving my arms around—“Hey, look at me!”– the reaction to My Green Manifesto has been heartening. That reaction—and I use this phrase for the first time in my writing life—exceeded my expectations. I am very fond of My Green Manifesto; it is goofy and loveable like a little brother. But now it’s big brother’s turn. Because whatever the world’s reaction, I’m pretty sure of this: the Gulf book is the best thing I have ever done.

* * *

I’ll paste the book’s first page below. At first I had the whole Prelude in the second person but now I just use it for these few short paragraphs.

From The Prelude: Into the Gulf

It is June and you are at a cookout at a friend’s house, a barbeque with all the kids playing in the backyard. You have just gotten back from traveling and you are happy to be home. For the last fifty-nine days millions of gallons of oil have been gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, but that is not your concern, not your problem. You want nothing to do with yet another dismal, depressing environmental story. You live in North Carolina and the Gulf is almost a thousand miles away. Yes, you care about the environment, so you should be thinking about the oil spill, but you’ve put on blinders, as you often do when the harsh light of big news events blares down on you. There is too much to think about, after all, and right now you are looking out at your daughter jumping on a trampoline, and the spill is the furthest thing from your mind. You drink your second beer and think that life is pretty good, pretty good indeed.

But then suddenly a friend is standing in front of you, and he insists on talking about the spill. He tells you of a live video stream he has seen from a mile below the surface and of the sight of a single curious eel peering at black-red goo pouring from the spill’s source, the busted Macondo well. He wonders what it is like for the people living down in the Gulf, and despite yourself and the beer and the sun on your face and your happy daughter playing, you start to wonder too. “You should be down there,” he says. “You write about nature.” You start to explain that that is not the kind of nature you write about—you write about birds and the coast, and you are not a journalist who chases stories. But then you stop explaining, and defending, and think simply: “Maybe he’s right.”

Over the next week the idea builds in your head. Maybe the Gulf is where you should be. Summer plans, family plans, rearrange themselves in your brain. You have a somewhat strained talk with your wife about your new plans, and, since there is no other way to get there on short notice, you decide to drive. “When will you go?” your wife asks, and it turns out your answer is “Right away.”

A magazine gives you an assignment to cover the looming fall bird migration, but this is about more than birds, you know that already. When you finally decide to leave you do so in a mad rush, throwing everything in the back of your car and heading out without any real plan. Of course you are aware of the hypocrisy of traveling eight hundred miles in a vehicle powered by a refined version of the same substance that is still pouring out into the Gulf waters—but now you are driven. Now you need to see the oil. You’re not sure why. You have heard the Gulf called a “national sacrifice zone,” and maybe you want to explore this idea of sacrifice, of giving up some of our land, and our people, so the rest of us can keep living the way we do. So you go down, heading toward the Gulf.

Great intro, can sense the pace, and feel the urgency in your journey. Hmmmm……… journey – journalism. Coincidence?? Some stories have to be experienced, not just thought about. Seems like most of your writing is like that.

Dave, the book is already available on Kindle and at Porter Square books in Cambridge! And I have been reading it now for the last too days. Its fabulous. I am alternately angry and despondent (i’m involved in the tar sands action and the capitulation of our administration is confounding), and hopeful and taken away by the beauty that you describe. Thanks!

can’t wait to read the new book, and the previous one too. oops, sorry I’m so late. love the thought of you throwing everything in the car in a rush and heading down there. just the way I’d be.

In the best literary tradition, not just narrowly journalistic, you went out and slew the dragon and dragged it back to the cave for us. Journalism is far too important to be left to the Journalists, and writers never have. Congratulations.

2 thoughts I already have from your book (half way through it).

1. Nature best thing America has going for it.

2.Its time to realize that Nature is as important if not more important as Religion. Its not easy to distort the way Religion is.

An important book and as always I enjoy the humor & humanity of it.

I can’t wait to read this book, David. It’s hard to believe that the spill barely happened more than a year ago, and yet it seems it has been wiped from our collective consciousness by idiotic things like debt ceiling negotiations and presidential debates that are nothing more than a new form of reality television. Hopefully this book will bring the conversation back around to what happened and what the lasting effects are.

Thanks Matt. That makes me feel very good.