Mar 28

All content ©2012 David Gessner and Bill Roorbach.

Site by Subpar Design.

Site by Subpar Design.

- Bad Advice (for writers, readers, and everyone else)

- march 21, 2012

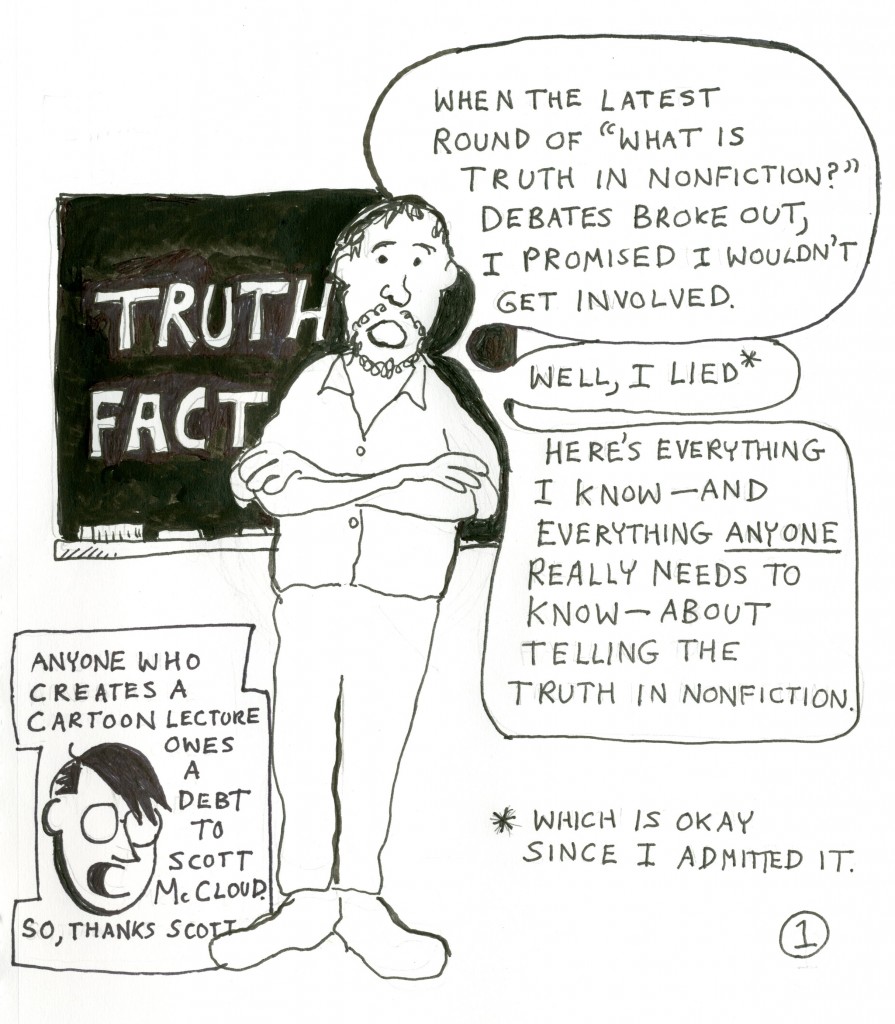

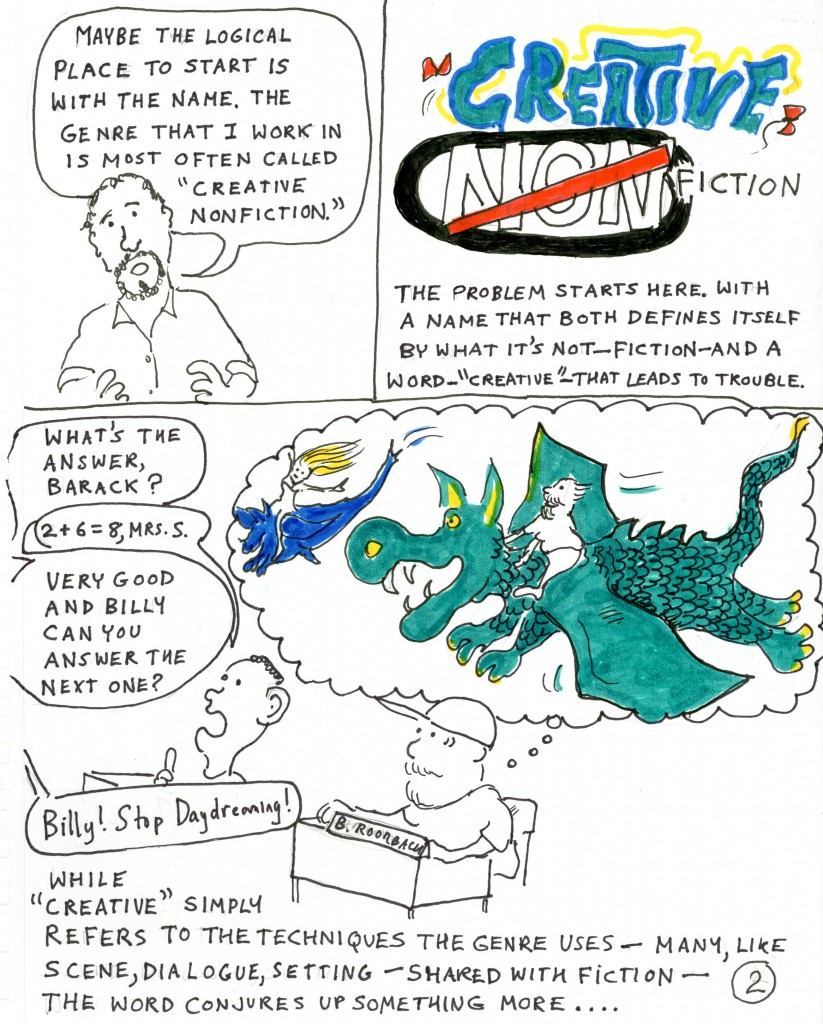

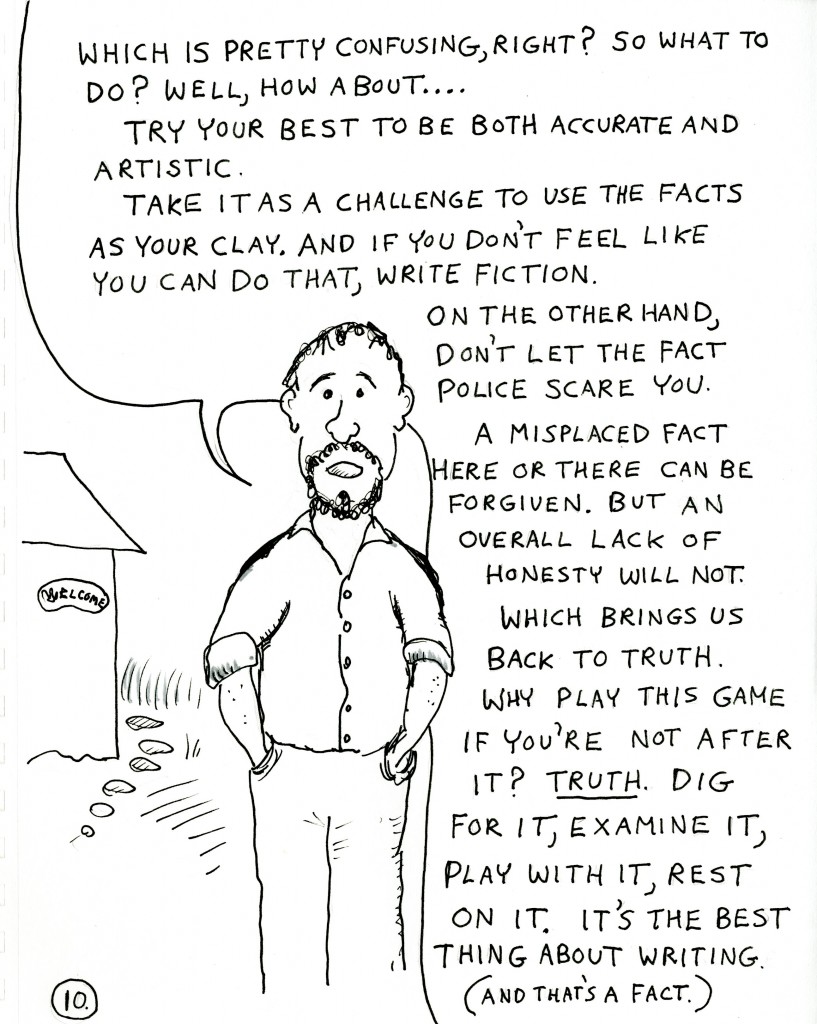

- Talking to Ghosts: Dave’s Cartoon Series

- I Used to Play in Bands: Bill’s Video Memoir

- Hair of the Dog: Cocktail Hour Archives

- Reading Under the Influence

- Podcasts

- Our Best American Essays

- Cartoon Archive

- Movies

- Bill and Dave’s Lounge

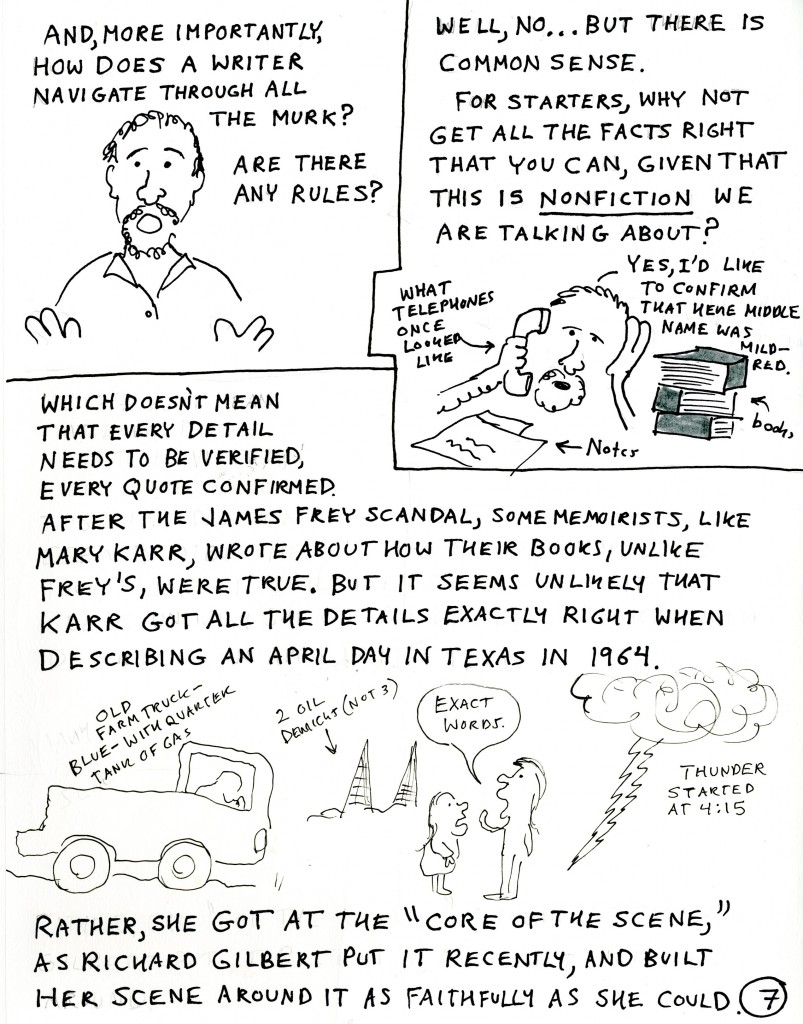

Thanks for coming up with this explanation and drawing it all out. I’d like to post it on my classroom blog and use it with my high school creative writing classes. I’m always looking for one more way to talk about the topic of truth vs exact replication. It’s a tough line for young writers. Often they just give up on a story if they can’t remember exact lines of dialog or the precise day of the month. My problem is more getting them to loosen up so they’re not suppressed by their own black-and-white version of the truth.

“Don’t go near it, Earl. It’s one of them nonfictiony things.” Best line I’ve read all day.

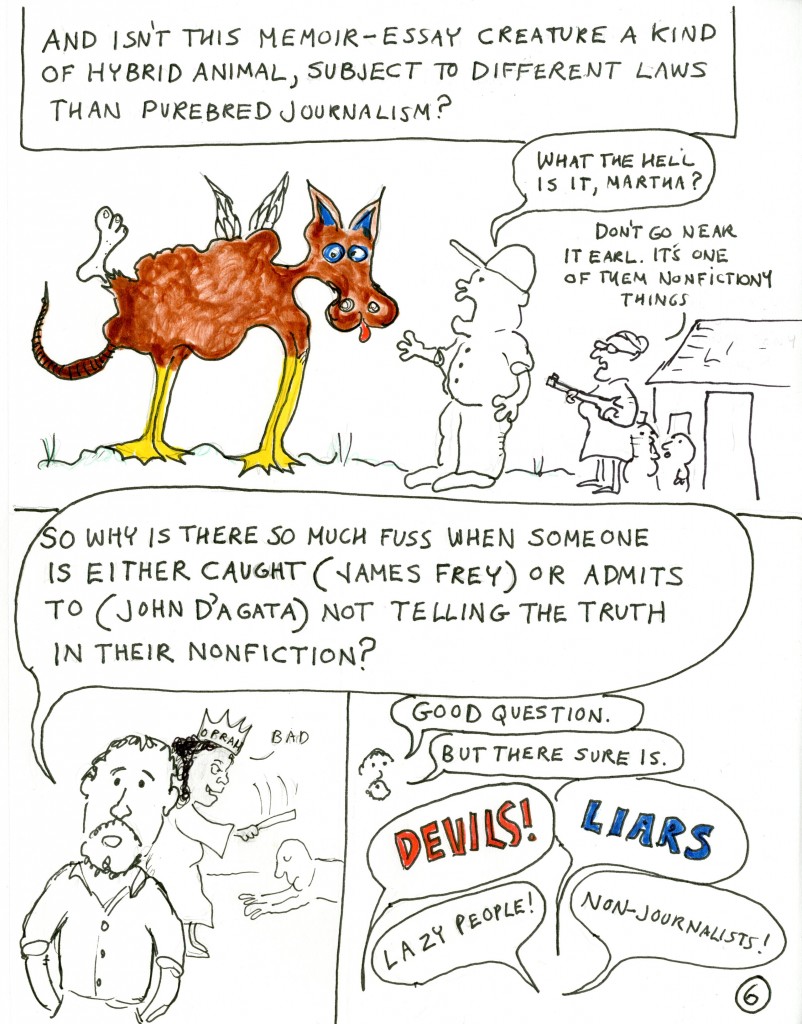

Thanks for trying to clarify a confusing but important issue. I’m with Nichole. I always thought CNF was a more difficult genre to do well because all that was available to the writer were the facts and his or her own skill with words. There were no plot tricks or outrageous characters that could be brought in to make the story work how the writer wanted it. As someone now stretching new memoir muscles, all of this recent discussion about truth/fact and CNF has been an education.

Truth/fact? I was at least 40 before I understood the difference, and I’m still shaving it down to a finer distinction. There’s the high plain of truth, to be sure, and there’s the dry plain of fact; between those two there’s the blended lowland in which most of us reside. I think Monica’s got it right, though – is the author intentionally lying?

You mean George Washington may not have actually chopped down a cherry tree, or he had, may not have admitted to it with his oft quoted, “I cannot tell a lie…..”

That story never happened. It’s been proven a myth many times.

It’s nice you gave a shout out to Scott McCloud. He’s a really smart guy and a wonderful human being. However, you really needed to acknowledge Larry Gonick; he was doing nonfiction comics long before Scott.

Don’t know Larry’s work but I will now. When I mentioned Scott, I was thinking specifically of the cartoon lecture.

Looking forward to Larry’s stuff. Might have to blog about it.

Depends on the insect? If there were really a 6-year cicada, that would mean 6 years of darkness and sipping on tree roots before that one final month of sex and sunlight. That still feels a little out of balance to me. What insect would you choose?

Something of the blood-sucking variety.

My friend and I are both having problems with nonfiction pieces we’re penning. He wants to slim down his 30 pages of CNF about a place he used to work, esp. bc of the potential of hurting someone’s feelings; I have toyed with changing a CNF piece into fiction simply bc I’m changing around the sequence of actual events. In the end I’ve opted against fictionalizing mine, and am trying to convince my friend to do the same. Why?

Writing CNF takes far more courage than writing fiction. One can always hide behind the label of fiction, make characters do what they want, manipulate, create a perfect little world. In CNF there is no perfect world, only a moment to capture, a method for putting permanently down a story you would tell a friend, neighbor, colleague, spouse over tea– or shots, as the case may be.

CNF inherently makes itself poignant. The reader of an honest, meaningful story is moved by the writer’s experience, feels closer to the writer (that ever-lovin’ R/W relationship) like a trusted pal, and can be moved by your candor and your confidences about the ‘characters’ in your piece.

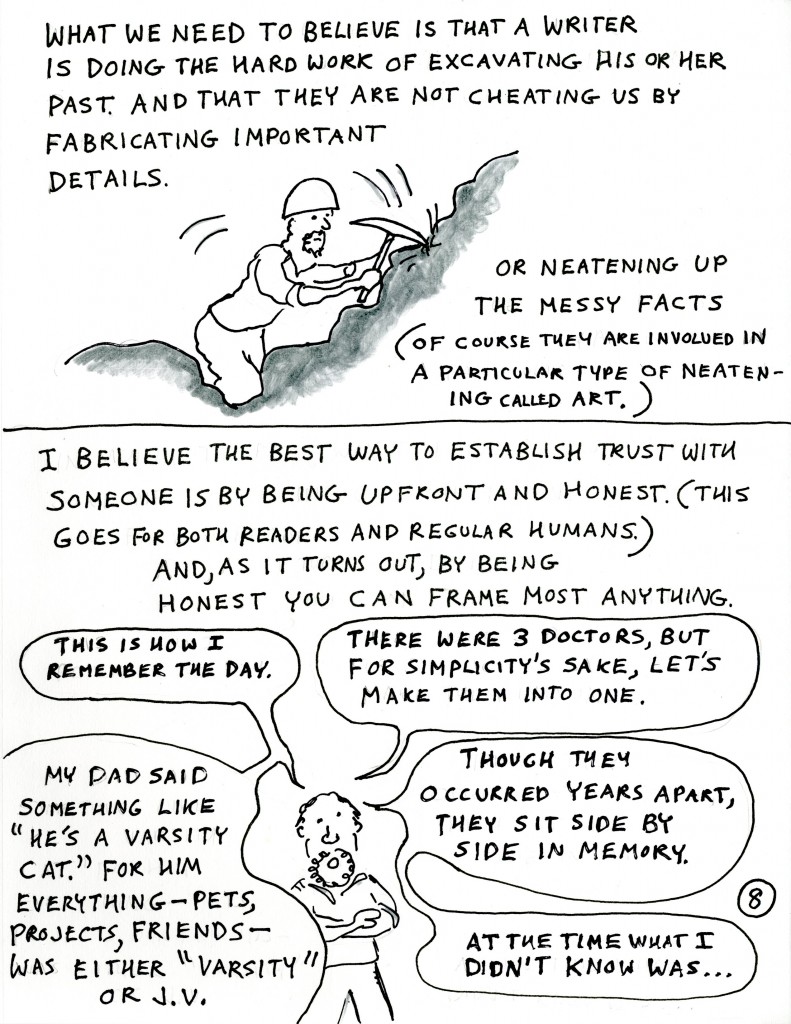

It’s the conversation a CNF writer has with her readers that make it such a touching experience. And it’s one I trust more than the manipulated writing of John Irving or Salman Rushdie, who deliberately play with you than congratulate themselves in their own work by pointing out their own tricks. Instead of playing tricks on my readers, wouldn’t it be more honest to make friends with them and admit when we make mistakes?

It takes more confidence as a writer. It requires more honesty, which Hemingway might have loved. It builds us as writers, and as readers even. In my case, my overarching attempt is not to make the work sound whiny or hyper-feminine. That’s all too often the damper in CNF. Instead this new writer is flexing her literary muscles.

Cheers. Thanks for a(nother) compelling post.

Nichole L. Reber

http://www.architecturetravelwriter.com/

@NicholeLReber

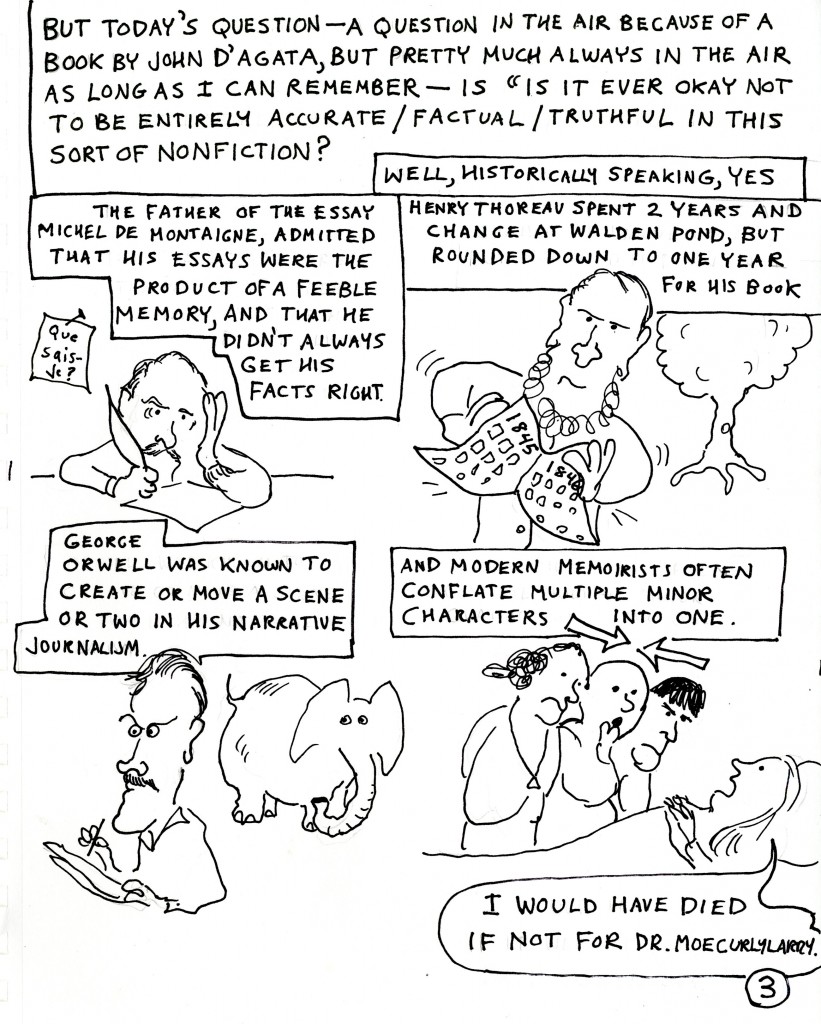

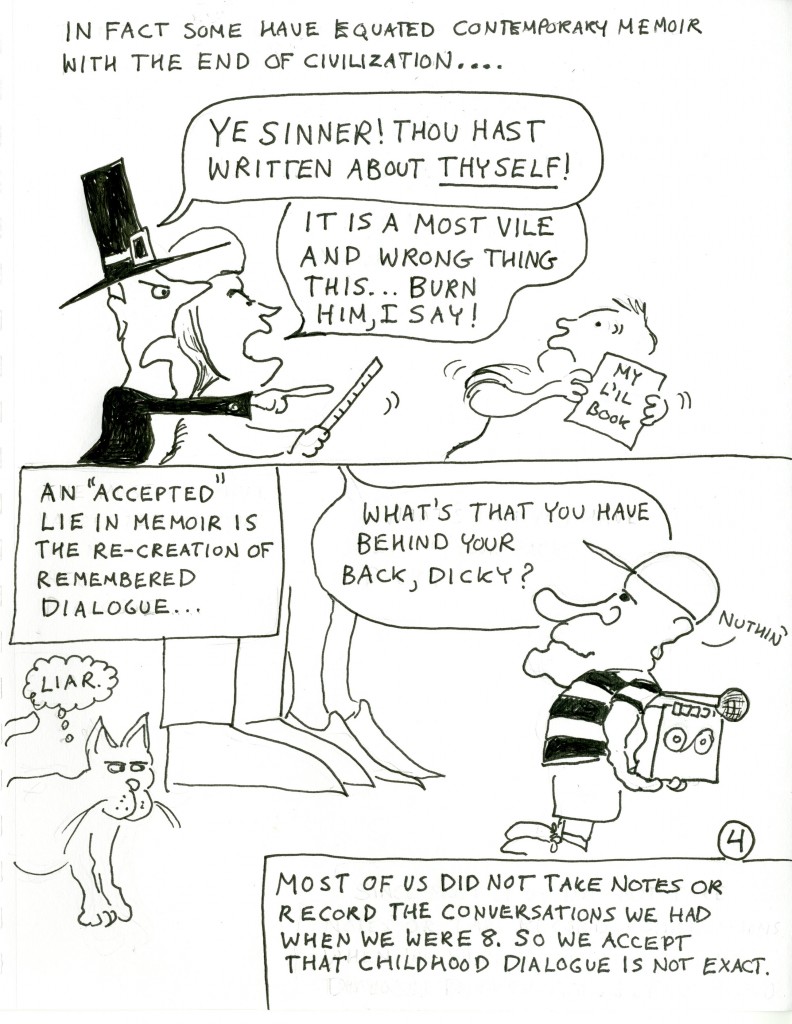

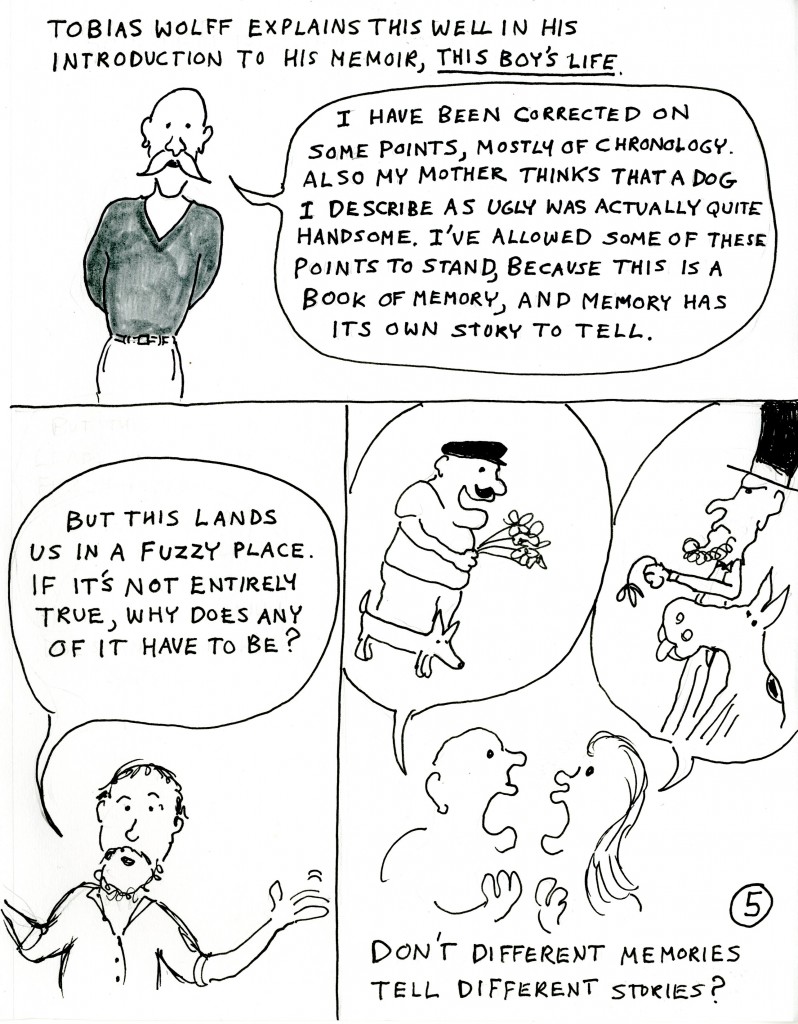

Thank you, Dave. So well said (and drawn), and the most compassionate argument I’ve read so far. Memoir is inherently going to be filled with perceived error; anyone with a sibling knows how that goes. Any of us who has ever told or heard a story on the front porch knows, and appreciates, that once a story begins, it begins to change. We make Uncle Bill a little taller, Auntie Mabel a little sterner, Dad a little more oddball, Mom a little more beautiful. That’s a human being telling a story; always was, always will be. Those aren’t lies; those are the wishful, endearing, often subconscious qualities of memory. But the point, always, is this: are you willfully lying? D’Agata was. Frey was. Wolff wasn’t. Who doesn’t want to love a memoirist who tries, as hard as he can, to get to the truth of his experience?

We used to call this part of story-telling – “writer’s embellishment”! I used to cringe when I would watch biographies or rockumentaries on t.v. and the biographer would interview somone’s ex-spouse, or a failed business partner, giving them the voice of authority. Who do you want to tell your story? My ex-wife’s version of my story is much different than other people’s closer to me. Do your readers need to trust in what you are telling them, or should we all just believe that everyone might be fabricating the parts of their story we find hard to believe?

And thank you, Monica. I’m looking forward to the book of your collected comments that will be published some day.

I feel bad for folks like Wolff, Eggers, and Hemingway to be used in…defense?…of D’Agata. It’s sad.

Those authors sought to write the truth to the best of their ability, and when they knew they may have failed at certain points, they alerted readers to their potential shortcomings.

D’Agata is a coward in comparison and did something utterly different than those authors: he made the decision to intentionally lie and manipulate readers.

I don’t feel I was defending D’Agata. I was using this, the latest flare up in a fire that never dies, to speak to issues that my students care about. D’Agata is a freak case in my opinion. The people who really need help are those young writers who are trying to write memoir/essay now and feel bullied by both sides.

Interestingly, the Hemingway quotation is not by Hemingway–at least not entirely. The Preface to A Moveable Feast was constructed posthumously by his wife, Mary Hemingway, using manuscript fragments. (This condition of its production makes the quotation kind of a funny piece of evidence to use when discussing writerly “truth”).

Even better!

I’m curious if you’ve read Lifespan of a Fact all the way through or are basing this on hearsay in the whole D’Agata kerfuffle? I hardly think changing the color of bricks from brown to red in his book (for example) is the same as intentionally misleading anyone about the events that happened. The point he was making is that these tiny details don’t alter the truth of the overall narrative in any substantive way, yet they can enhance the metaphor that speaks to the broader truth.

Oh, I think D’Agata changed a lot more than just the color of the bricks. I have read the book, and in fact I use it to help my journalism students understand the issue. He changed things like the number of people who died on a given day from heart attacks, for example. And there’s just no need to change that. You really couldn’t argue that it advanced the story in some profound way.

David, I love the way you break down a complicated issue into something that is frank, honest, and makes sense as a model for other writers of whatever-you-want-to-call-it to follow. Also, there’s a fascinating piece on this same topic on This American Life, examining the controversy over Mike Daisy’s monologue about Apple’s factories in China. Daisy, apparently played with facts in a pretty alarming way. If you want to listen to it, it’s called “Retraction.”

Yes, the Retraction piece is amazing. Shades of James Frey in Daisy’s cowering. But aren’t you in some foreign land? They got this here internet over there?

Believe it or not, they have internet here in Budapest!

Doesn’t that take some of the fun out of travel? (Though on the plus side you get to read Bill and Dave’s.)

I want my whole online life to be as humorous, well-illustrated and calmly opinionated as this piece.

This makes me happy. Or as the young people say, “Like.”

Hey, David, thanks for providing me with a partial lesson plan for my Intro to Creative Nonfiction class! I love this, and I think we should discuss this a bit more in our classes.

Two responses:

1. Ha!

2. Brilliant. Especially regarding memoir.

3. Sensible*

Yeah, I can’t count. Which is another way fiction or art or just plain old grace notes seep in: we’re flawed brokenhearted creatures. And we need stories to survive.

Well done and TRUE.

I find this comforting and hilarious. Well done and charming, I might add.

My memoir is likely full of holes, but common sense prevails…I don’t really care. Age has its excuses.

Well done, Dave. The middle way is, I think, the way to go. I’ll share this with my students, who find it as confusing as the rest of us do.

Yeah, it’s a noggin-buster. But I like that we have this conversation periodically. Otherwise we literary types would just join the wholesale romp towards truthiness currently underway in the worlds of reality television, Fox News and superPACs.

I have also felt for some time that memoir needs to be its own genre, separate even from creative nonfiction. Sort of like a teenager with mono.

It’s like the locusts but it comes back every 6 years.

The difference is that the locusts make their point (have sex) and die. That’s a fact. But this new hybridized writer seems unable to make their point (lives in a perpetual state of foreplay). That’s the truth.

I’ve always thought it would be better for most writers to be more like insects. Food for birds.

This discussion has always made my head hurt.