Guest contributor: Richard Gilbert

DFW on CNF: Deconstructing David Foster Wallace

categories: Cocktail Hour / Guest Columns / Reading Under the Influence

3 comments

“. .. personal essays and memoirs, profiles, nature and travel writing, narrative essays, observational or descriptive essays, general-interest technical writing, argumentative or idea-based essays, general-interest criticism, literary journalism, and so on.” —David Foster Wallace’s syllabus definition of creative nonfiction.

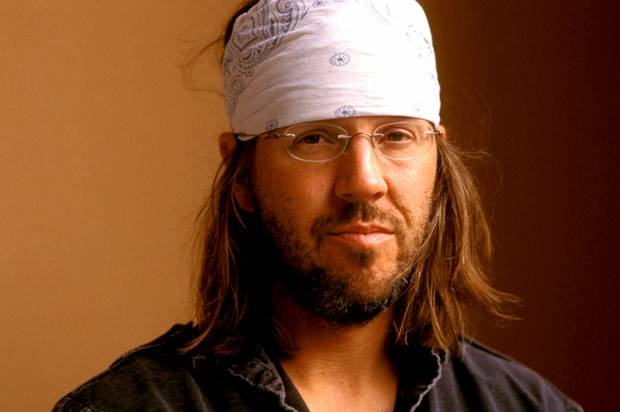

As a teacher and writer of nonfiction, I devoured the late David Foster Wallace’s recently released creative nonfiction syllabus. Salon, which published it, called the document “mind-blowing,” evidently referring to its tough-love language. In this blueprint for a night class he taught at Pomona College once a week in Spring 2008—so roughly six months before his death, presumably when he was already suffering from deep depression—Wallace prosecutes a rigorous, distilled aesthetic. He builds toward it in his opening “Description of Class,” which notes that “nonfiction” means it corresponds to real affairs but that creative “signifies that some goal(s) other than sheer truthfulness motivates the writer and informs her work.”

This purpose may be “to interest readers, or to instruct them, or to entertain them, to move or persuade, to edify, to redeem, to amuse, to get readers to look more closely at or think more deeply about something that’s worth their attention. . . or some combination(s) of these.’’ He continues, going deeper:

Creative also suggests that this kind of nonfiction tends to bear traces of its own artificing; the essay’s author usually wants us to see and understand her as the text’s maker. This does not, however, mean that an essayist’s main goal is simply to “share” or “express herself” or whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school. In the grown-up world, creative nonfiction is not expressive writing but rather communicative writing. And an axiom of communicative writing is that the reader does not automatically care about you (the writer), nor does she find you fascinating as a person, nor does she feel a deep natural interest in the same things that interest you. The reader, in fact, will feel about you, your subject, and your essay only what your written words themselves induce her to feel.

Creative also suggests that this kind of nonfiction tends to bear traces of its own artificing; the essay’s author usually wants us to see and understand her as the text’s maker. This does not, however, mean that an essayist’s main goal is simply to “share” or “express herself” or whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school. In the grown-up world, creative nonfiction is not expressive writing but rather communicative writing. And an axiom of communicative writing is that the reader does not automatically care about you (the writer), nor does she find you fascinating as a person, nor does she feel a deep natural interest in the same things that interest you. The reader, in fact, will feel about you, your subject, and your essay only what your written words themselves induce her to feel.

The apparent acid that Salon responded to in “whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school,” I read, instead, as an attempt to emphasize his own hard-won understanding. It’s not just that along the line Wallace got his ears bored off by some undergraduates’ essays, though there’s a whiff of that. In the recent Quack This Way: David Foster Wallace and Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing, Wallace discusses how in college he “snapped to it perhaps late,” thanks to his teachers, that the world “doesn’t care about you. You want it to? Make it. Make it care” (33-34).

Also he’s trying to woo his students by inviting them into his world’s inner sanctum. We will learn what only the pros know. His brief for art over experience is a key aesthetic principle of literary nonfiction. Since such prose is often initially motivated by deeply personal experiences and feelings, which often it also does express, it can be a revelation to writers to learn that that’s not enough.

As I read it, Wallace is not forbidding heartfelt personal writing but simply saying that the fact that the experience was personal or cathartic for the writer isn’t sufficient. High levels of craft, which themselves bespeak authorial distance and shaping, must be brought to bear. Attention must be paid … to the reader.

As he explains:

Part of the grades you receive on written work in this course will depend on each document’s presentation. Presentation here means evidence of care, of facility in written English, and of empathy for your readers. The essays you submit for group discussion need to be carefully proofread and edited for typos, misspellings, garbled constructions, and basic errors in usage and/or punctuation. “Creative” or not, E183D is an upper-division writing class, and work that appears sloppy or semiliterate will not be accepted for credit: you’ll have to redo the piece and turn it back in, and there will be a grade penalty — a really severe one if it happens more than once.

David Foster Wallace’s list of essays for student reading

For a class session early in the semester his students were to read Jo Ann Beard’s “Werner,” Stephen Elliott’s “Where I Slept,” George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” and Donna Steiner’s “Cold.” For the next class they were to read David Gessner’s “Learning to Surf,” Kathryn Harrison’s “The Forest of Memory,” Hester Kaplan’s “The Private Life of Skin,” and George Saunders’s “The Braindead Megaphone.”

If this seems light reading for a semester’s writing class, recall that, because his English 183 class is small, he’s running it as one big workshop group. Each student must read, edit, and write about several classmate essays per workshop session. As far as I can tell, after the introductory class and two on these readings—so after about three weeks to get the students writing—the class’s three-hour weekly sessions were spent discussing student work.

By having them read these essays at the start, he was both giving his students sophisticated models and filling in until their essays came rolling in. In the same way that he asked them to respond to their classmates later, he gave his students this assignment for each group of essays:

Pick one of these essays, pretend that it’s been written and distributed by an E183D colleague, and write a practice letter of response to it, being as specific and helpful as possible in detailing your impressions and reactions and suggestions for how the essay might be improved.

I asked David Gessner how he felt about Wallace teaching his “Learning to Surf,” which was published by Orion. The essay braids Gessner’s learning to surf with his experience of being a father to a young daughter and with his increasing interest in the mute, prehistoric-looking pelicans that ride the ocean breezes past the middle-aged Gessner and his fellow teenybopper surfers as they try to catch waves. I think Wallace used “Learning to Surf” because it’s well-written, interestingly structured, and something students might relate to or try to emulate (surfing, writing about multiple subjects, noticing nature and especially birds). However, Wallace’s friend Jonathan Franzen, an avid birdwatcher, has written about Wallace’s antipathy to that passion. Which raises a question about Wallace’s feelings about the whole nature-writing genre.

“I was surprised that DFW taught my essay in his class,” David responded. “I had assumed he was not too crazy about it, as it was a finalist that he did not pick for the Best American Essays the year he chose them. In the intro to that collection, he said he had few definite criteria for choosing the essays, except for ‘no essays about geese and things,’ which I assumed included pelicans, the subject of my essay. So it was a pleasant surprise that he even noticed the essay.”

The genius writer as yeoman teacher

Wallace’s syllabus also interested me for how it reveals the brilliant novelist and essayist as a beleaguered teacher of undergraduates. This class was limited to—praise the Lord!—twelve students. At most institutions, I imagine, the cap would be 16. As writing classes edge above 16 and reach 20 or more students, things get much less personal for everyone. Some students feel they can hide. Instructors simply cannot give each writer as much attention.

So, in prepping his artisanal class, it is amusing to see Wallace practicing the jiu-jitsu common to all teachers who author syllabi. It’s a loss of innocence, what you learn you must include. But it’s also good and necessary housekeeping. Here’s his statement on attendance:

For obvious reasons, you’re required to attend every class. An absence will be excused only under extraordinary circumstances. Having more than one excused absence, and any unexcused ones at all, will result in a lowered final grade. After the first two weeks, chronic or flagrant tardiness will count as an unexcused absence.

That Wallace had to write the next line is rather heartbreaking but it proves he did teach undergraduates:

All assigned work needs to be totally completed by the time class starts.

I can’t remember students in my day using broken typewriter ribbons as excuses, though surely some did; I vaguely recall faded type from frayed ribbons. Now the technological aspect of writing is vast. Especially if work is shared electronically, but there’s also more formatting—the old typesetter’s job—even for hard copies. For both student and teacher, much more knowledge and tools are required. I spend a huge amount of time teaching things like proper formatting in Microsoft Word, including telling students repeatedly to notice and override Word’s annoying default of putting extra space between paragraphs. (Fine for the web, but . . . )

Students have many more real and convenient excuses for late work, including trying to use a web-browsing device as their workhorse computer, lacking compatible software, or composing essays on thumb drives. Periodically I’m asked by students to email them essays because they can’t find drafts in their computers, have a broken hard drive, or have lost the thumb drives they trusted them to. And always, real but foreseeable (to an adult) printer pitfalls—including dry ink cartridges and empty paper trays—crossbreed with immaturity and procrastination. Technology both permits sharing and provides excuses that drive teachers half mad.

Here is Wallace’s valiant, doomed effort to head off the latter:

There are no “extensions” in workshop-type classes; your deadlines are obligations to [12] other adults. Finish editing and revising far enough ahead of time that you can accommodate computer or printer snafus.

Each of his students was allotted three workshops. Except some, he knew, would want one fewer or need one more. Here he tries to engage students in the logistical aspects of workshopping—as if they’ll remember or care that he’ll have to juggle like a demon to accommodate custom experiences:

This is not impossible, but it makes for tricky scheduling — you need to confer with me individually (and soon) if you wish to submit something other than the normal three pieces.

Although a teacher labors to plug the holes and scare the hardened criminals, he learns repeatedly that he’s fair game. And that even good students don’t know the impact of their messy lives on a teacher with dozens of other students to tend and hundreds of pages to grade. Sometimes he imagines good students puzzling over syllabus invective spurred by the sins of their unknown miscreant forebears. As Dave says, it’s tricky.

One of the ways Wallace handles these paradoxes of the teacher’s role is with humor. He’s spoofing his authority even as he establishes it. It’s clear he’s no ogre. Telling his students “you’re insane” if you don’t own a good dictionary and a usage dictionary makes the serious ones feel special—they’ll buy one or both. By all accounts, he was uncommonly attentive and kind to students.

Any student with half a brain got the humor and smelled the fudge factor here:

Attendance, Quality & Quantity of Participation, Effort, Improvement, Alacrity of Carriage, Etc. = 20%.

I’m surprised only that he didn’t list “Deportment,” but surely that’s included under Alacrity of Carriage.

Richard Gilbert teaches at Otterbein University and is the author of Shepherd: A Memoir. His essays have appeared in Brevity, Chautauqua, Fourth Genre, Orion, River Teeth, and Utne Reader.

Richard Gilbert teaches at Otterbein University and is the author of Shepherd: A Memoir. His essays have appeared in Brevity, Chautauqua, Fourth Genre, Orion, River Teeth, and Utne Reader.

Richard, this is great. Thanks for sharing it. I love David Foster Wallace and love teaching classes that are in the same vein–where there is no false, or faulty limitation on what might be. Class is more like a state of being…bring your excellence and all of your thoughts–disturbed, frightened, pissed-off, joyful, enlightened or otherwise–or go home, cause there is little point. The classes where I push the boundaries are always the classes that my students most enjoy and are most engaged and successful in. And these are the classes where the person who drops in to review my work notes problems. LOL. People just LOVE those boxes. I can’t understand it. But I can’t make that statement without also saying that back when I was teaching eighth grade in an inner-city district and my students’ proficiency test scores in reading and writing were soaring, I got a lot of credit from the principal. Of course it wasn’t my skill, it was just that I released my students from those boxes, and they got to be amazing. Ah, see Richard, now you’ve gone and made me miss teaching…

Anyway, there is a big gap in the world without DFW. And it’s so totally cool that he liked to use a David Gessner essay in his class.

Thanks, Debora! You have underscored something important: the soaring possibility he allowed, allied with high standards. As I tell my cnf students, “You can do anything you want, as long as it works.” True. Same as for fiction or any art.

My secret DFW crush here is that he did care about form, as a craftsman and as evidence of courtesy to the reader. Some teachers don’t see the craft aspects he could not ignore. He did not consider them lowly. At the same time, he urged them to swing for the fence – and all aspects of form were part of that.

Yes! I agree with you and DFW about form–Not a free for all. There has to be purpose. The artistic must function in the unified whole.