Guest contributor: John Lane

Bad Advice Wednesday: Write Everything!

categories: Cocktail Hour

1 comment

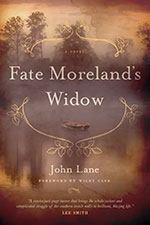

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.

I didn’t plan to have a literary career, much less have it unfold this way by the time I turned sixty. When I was twenty-five I saw myself primarily as a poet and because of that, I didn’t see my choice as vocational. Nobody made a career out of poetry in 1979—except maybe Robert Bly, and I didn’t look good in a serape. Instead I considered what I was doing a calling. I even believed in the muses, particularly the muse of lyric poetry. Back in the Seventies, I believed the muse called for a stern steely-eyed focus on art. I believed she asked for total sacrifice, and particularly poverty. If I were to achieve any level of literary achievement, I would have to focus for years on the art of poetry alone. I would distill my voice and create with it a pure poetic acid to burn away all impurities of living a normal life. Or something like that.

So how to get there? How to find the time? The MFA programs were just taking off in the 1970s, so I didn’t go to graduate school right away; I did other things to support my calling—traveling, landing a grant to learn letterpress printing at Copper Canyon Press, working as a cook. I did not wear a beret, but it wouldn’t’ have surprised my friends if I had. As a twenty-something, I was that kind of poetry guy.

My “bad advice” back then would have been to write just one thing, and write it all the time, to go for Kierkegaard’s “purity of heart.” I might have might said, “Write only what you want when you want,” or, to crib a famous Joseph Campbell quote, “Follow your bliss into an endless mutating dance with your own creativity through time.”

But then my attention began to wander to other genres. I began to spread out. I jumped the out of the poetry channel; I discovered my flood plain was wide. I started reading Annie Dillard, Joan Didion, Edward Hoagland, and Barry Lopez and fell in love with their lyrical prose. By 1984 I’d published a bunch of poems in magazines and one small book, but I wanted to take a stab at emulating the prose writers I loved, and I found a magazine ready to pay me to write prose, the Sunday supplement for the largest circulation newspaper in South Carolina. The editor liked my poetry and said, “Write first person essays, and I’ll publish them.”

So I set about writing whatever occurred to me: a piece praising the lay-up over the dunk, a day’s worth of meals in a single town, a road trip from the mountains to the coast, a strange piece called “cloth confessions” about my love natural fabric shirts.

Once I’d begun writing prose fiction seemed the likely reach. I began to wonder: if Ed Abbey could write The Monkey Wrench Gang, Harry Crews Naked in the Garden Hills, Walker Percy The Moviegoer, and Clyde Edgerton Rainy, then why could I not write a novel too? I had stories. I could make up characters.

So at the same time I began to be seduced into first the emerging third-genre work by having a working relationship with a magazine to write what we now call “creative nonfiction” or the personal essay, I began my twenty-year apprenticeship in learning how to write a novel.

It wasn’t easy, but no one said it would be. The first novel I started was in the late 70s and was called The Sawgrass Rebellion, and it was sort of The Monkey Wrench Gang meets The Moviegoer, if you can imagine that. Its sensive young protagonist, Duncan Daniels, was a lot like me—a nature boy who read Kierkegaard, bent on saving the wild world world from the grasp of late stage Capitalism. I had about 130 type-written pages of that one when I abandoned it. No one ever saw it. I remained primarily a poet.

Next in the middle1980s I wrote an adventure novel with a close friend. It was called A Revolution of the Heart. Set in Belize, the protagonist (Peter Conrad) was just like my friend and co-writer, a crocodile biologist. The story owed a lot to one we admired, Heart of Darkness. Our hero Peter Conrad and his side-kicks battled drug-running poachers, another form of late-stages Capitalism. We finished the novel, landed an agent, and it was rejected twenty-seven times in New York.

Twenty-seven rejections wasn’t enough to stop me. In the late 1980s the agent convinced me to complete a novel about a high school basketball team during the integration of southern schools, something I’d experienced as a teenager. Called The Point Guard, I finished the manuscript, narrated by a 15-year-old player named, once again, Duncan Daniels. The book was set in a mythical town called Morgan, South Carolina, a post-textile community in the rolling hills east of the Blue Ridge, and it was about a friendship between Duncan and an African-American player on the team and their mutual struggle against a racist coach. The agent, upon first reading, was convinced it was an adolescent novel. I was not. He pitched it that way, and it soon out-paced A Revolution of the Heart in rejections.

The final attempt at a novel before I wrote and successfully placed Fate Moreland’s Widow was one a farce called Dirty Money. It did not contain a single character named Duncan Daniels, though I felt compelled once again to set it in my mythical Morgan County again, my personal Yoknapatawpha County. The story this time was about a small waste management company, late-stage Capitalism run amok once again. A man approaching eighty, the gullible but lovable Darrell Crosstie, had decided to give his fortune made in the garbage business to endow a local struggling college, only to find out as the action processed that he did not have any money to give because his crooked brother-in-law and business partner for decades had bamboozled him out of it and cleverly kept him in the dark long enough to deeply embarrass the college. A new agent read it and said, “I like it, but can’t you make it sound more like Carl Haasen?” More rejections. More failure

After Dirty Money took the dive into the rejection box, I began to feel a little like the King in Monty Python and the Holy Grail whose castle keeps falling in the swamp. But that didn’t’ stop me. Then I got an idea for another story, one about the earlier gritty stages of Capitalism—the story of a 80-year-old retired textile mill accountant and boss’s right-hand-man who one day in 1988 is plunged back into 1935-36, the most complex years of his long life by an unexpected visit, and Ben Crocker, the narrator of Fate Moreland’s Widow was born. After almost five years of drafts I sent the copy off to USC’s new novel series, and here I am—poet, short story writer, playwright, personal essayist, song-writer, script-writer, billboard author, and, finally, at the beginning of my seventh decade, and novelist.

It’s only been out a month, but what differences do I see so far? Donald Hall says publishing a book of poetry can feel like clapping in an empty room. I’ve found that publishing a novel feels much more like clapping in a very crowded room and wondering if anyone will hear you clap. As I wait for the applause or the boos, I have time to reflect on whether or not I should have tried to play that single note of poetry until I had it perfected. I think not. I have never been bored with writing. I have never had an attention deficient or a bad case of writers block because I’m always changing directions, sometimes in mid-stream, sometimes after I’m firmly standing on the far bank.

I have actually paid close attention—to the myriad ways the human imagination can express itself in writing. I’ve learned not to look down on the writer of multi genres, or to turn up my nose at those with a single fierce focus. So if you want to, write everything. There were plenty of bars to leap over, and no matter how many times you fail, remember how good it felt the last time to land in the sawdust on the other side.

You have had interesting twists in your career. The 30s were interesting and hard times for the textile workers. I’ve recently reread Rick Bragg’s, The Most They Ever Had,” and a number of years ago read Doug Marlette (the late cartoonist) who wrote a novel about the textile strike.