Bad Advice Wednesday: Listen to Eli!

categories: Cocktail Hour

5 comments

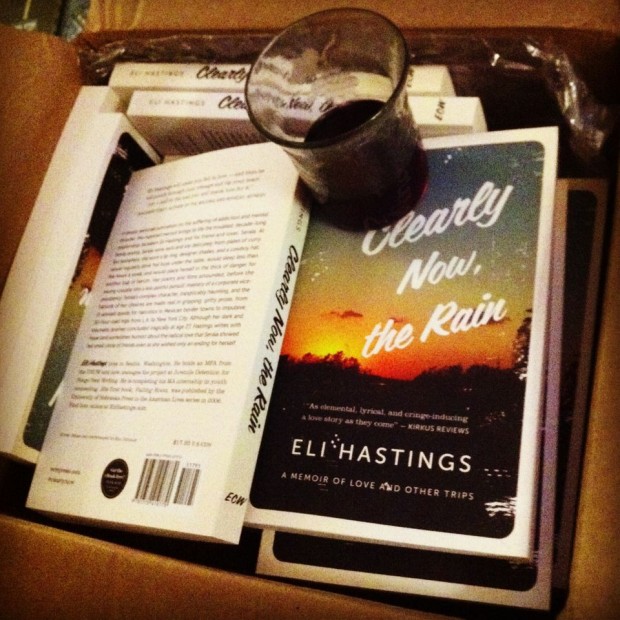

When we first conceived of this website we saw it as not just a celebration of writing and reading, but a party among friends. This week I am very proud to welcome former student, long-time friend and great writer, Eli Hastings to the party. Over the next three days we will highlight him and his forthcoming book, Clearly Now, The Rain.

When we first conceived of this website we saw it as not just a celebration of writing and reading, but a party among friends. This week I am very proud to welcome former student, long-time friend and great writer, Eli Hastings to the party. Over the next three days we will highlight him and his forthcoming book, Clearly Now, The Rain.

Kirkus Reviews had this to say about the book: “A candid, bracing memoir of love, addiction and self-destruction……As elemental, lyrical and cringe-inducing a love story as they come.” And Benjamin Percy added: “Eli Hastings will make you fall in love — and then he will punch through your ribcage and rip your heart out — and by the end of his moving memoir, Clearly Now, The Rain, you will thank him for it.”

Eli writes from the heart and in the essay below he describes how his book came to be:

No Straight Lines

I do not crisply remember the various moments that I said it. I think I said it once when Serala tucked me into her bed in 1998. I was raging and heartbroken over a girl; she gave me a few sips of her wine and sat against the wall stroking my head while I bitched and wept. I corkscrewed through black sleep for nine hours. My eyes snapped open on her and she was still dressed, still sitting there, still drinking wine, still stroking my head.

Maybe I said it once when she called from a locked ward’s payphone, the sounds of caged anguish around her, her voice dulled, reporting the cocktail of death she’d prepared and ingested, how all it did was land her there for a stomach pump and cross examinations.

I’m pretty sure I said it when she called me giddy one winter morning, celebrating that she’d made it from L.A. to Jersey in forty-seven hours, alone in her Corolla.

“You know, if you die, I’m going to write a book about you.”

And she’d scoff prettily and say, “You better.”

Or did I say, “When you die?”

Anyway, I meant it.

***

I graduated from the UNCW MFA program in 2004 with a few publications and a collection of essays that some people were sure would make a fine book. These works spanned my life, but not one of them mentioned my best friend. This was both by design and somehow natural; she was so tightly twined to my life that writing was almost like talking with my head in her lap on a hot Jersey night.

But the nibbles on the essay collection were few and far between. I roamed into long, creepy short stories as I roamed home, eventually, to Seattle, to a last-minute visit from Serala. Her lover had overdosed six months back; she had been released after another earnest attempt at death six days earlier. After a fantastically debauched Christmas in my late father’s house, she kissed me goodbye to go and score, despite my hollow protests. Despite the franticness of our two-day search, the cops found her first, in a Belltown alley just hours shy of 2005.

In January, I didn’t do my morning pages. I drank and raged and climbed up icy peaks in snowshoes and tumbled back down, crying and singing songs we used to love. I wandered the freezing streets from where I’d last seen her to where she’d been found, making up trajectories, painting ugly narratives against alley walls, stopping to punch some of them and throw back the cheap stuff in jam-packed skid row bars. In January, I’m still not sure I cared to live either. Maybe I was giving myself a brief window to play roulette because in February I had a month’s residency at the Vermont Studio Center and, if I made it, then I had a fucking book to write.

***

Johnston, Vermont, was having a mild winter. There were only four feet of snow. At dawn the sun was a greasy quarter overseeing the slow death of icicles on red barn eaves and skeleton Aspen fingers like a poem. My bohemian colleagues steered around me. I’d sobered up so I doubt I stunk. The scabs on my knuckles had mostly healed, but I felt both naked and guilty showing my eyes to anyone. I closed the door to my studio, sat down at a plywood desk, squared up piles of photos, letters, and mix tapes, stared at the blinking cursor for seventy minutes and then began to type.

I wrote 385 pages in fourteen days, nearly ten years of her, filtered through the various me’s that I revisited. I wrote it as a letter, in second person, telling her everything she already knew, trying to make her face my pain. The only person I spoke with much was a sweet Mexican printmaker who possessed no English and sometimes touched my shoulder. The night I finished the draft I drank two bottles of cheap red and got into bed for fourteen hours. Then I got up and revised for two weeks.

Of course I broke my promise—it wasn’t about her, only the measure of a decade between us.

***

At the end of the residency, I got another rejection for my essay collection. Like many, it was kind and laudatory; unlike others, the agent seemed sincerely sorry that an essay collection wouldn’t sell. I told him it didn’t matter, I had another manuscript that was much more important. I attached the file to the rejection email and hit send and went out and haunted dive bars where she and I used to go.

***

The agent was a big shot and a fast reader. He fell in love with the manuscript. This was back in the days of red ink and hard copies. By May, I’d written two new drafts, paring page-long soliloquies down, clearing the smoke from scenes that were impenetrable, and trying to figure out how to invite the reader into a one way conversation. The agent prepared his editor lists and out it went. Almost simultaneously a Spanish doctor reappeared in my life. I packed up for a move to Barcelona. The agent said there was no reason the book wouldn’t sell by my departure date three months hence.

On a layover in New York, splitting a bottle of merlot with an old friend in a faux-French bistro, dreaming about Mediterranean sun and cheaper bottles, rain coursing down the windowpane like a tide, my phone rang.

“You need to get down to Avenue of the Americas—there’s a junior editor at Monstrous Corporate Mainstream that is wild about your book,” the agent said.

In a tiny office I faced the junior editor, Rex—my age, exuding calm confidence, little golden hipster novels he’d midwifed piled around him.

“Tell me about Serala,” is what he said.

An hour later, he escorted me to his boss’s office. She was a knife-thin, predatory looking blonde. She was on her phone. We waited.

“We’re sooo excited about your novel—addiction really sells,” she cooed. Rex closed his eyes, briefly, in the doorway.

***

I published my essay collection with a courageous editor at the University of Nebraska Press, which felt like a nice blip on the radar instead of a long-coming coup. I shoehorned myself into a dark apartment in Barcelona with the doctor who would become my wife. I scrounged sawhorses and a slab of plywood and set up a desk and started working the blade around draft eight—per Rex’s direction. I was making the leap, transferring the whole thing to the third person, which felt like a betrayal but also necessary. Revisiting the story was like kindling the trauma every stinking morning, but hey, an offer was surely forthcoming. Besides, the woman I wanted to show I wasn’t an utter mess was working toward a PhD and doctoring all day, so toil felt proper.

On an oddly frigid June morning, I coaxed the butane bottle to life, set the café to boil and checked my email. The final answer was no. The predatory blonde wouldn’t sign off, presumably because the “addiction” piece wasn’t ready-made to sell. My agent was sorry and said it was unfair when editors did this. He was surprised and deflated. The A, B, and C editor lists had been exhausted. The rejections ranged wildly in motive: it was “too dark;” it was amazing but they wouldn’t touch it after the James Frey debacle; there wasn’t quite enough heroin chic; the voice was too abrasive; I was glorifying drugs and death. Of course, some simply didn’t like it. The agent suggested I write a novel.

***

The novel took me nearly five months to complete, but I didn’t have anything else to do. It took the agent one week to say he thought it was quite terrible (he was right). I took six months and wrote another. He said he admired it, but then tried to pass me on to his assistant. I torpedoed our relationship via email. I’d told myself that a novel was only a stepping stone to getting the memoir out—I believed it was the only way to honor Serala, the only way to bring closure, the only way for my wounds to close so I could love properly. The thought of it not seeing the light of day caused a quiet typhoon in my chest.

On a whim, I googled the junior editor, Rex. He’d left Monstrous Corporate Mainstream and started his own agency in part because they wouldn’t let him publish my book. I was starting to get intoxicating whiffs of fate. Many people had told me—and when it fit my mood, I’d told myself—that the book’s time hadn’t come. That the rejections were blessings in disguise. Maybe I was saving her family from premature pain. Maybe there were things that I needed to add. Maybe the final draft was still down the road, distilled by time and perspective. Maybe when the tumblers did fall into place the book would go big. But now—now it was time. Surely. I’d done another two drafts before writing Rex.

It took Rex year to throw in the towel, which he did after getting a hodgepodge of confusing rejections that gave no consensus whatsoever for another rewrite (also, a drunken, bitter, midnight email from me didn’t help).

Thus began about a year of tailoring proposals for small presses. I’d landed on the far end of the spectrum from my visions of major publisher ease. But the humble tumble down from that place had reformed my vision. I knew that if I could get the manuscript to a simply respectful home I could rest—that, in fact, a humble, literary home would be far better than trusting corporate marketers with something that was so sacred to me. I penned snarky announcements of indie publication to agents and editors in my head. Living in the Mediterranean, I was maybe less aware than I should have been that the bottom was falling out of the book industry. Except for the good people at Tupelo Press who sent an “almost, so close, but something’s not quite right” rejection letter, I didn’t get a single nibble. Both literally and symbolically I hurled the manuscript into a drawer and slammed it shut. I tried to live with that drawer locked.

***

In the year that followed we moved back to the U.S. and I wrote from a place that was half anger and half love, half joyous and half sorrowful. I wrote another novel, essays, short stories. I wrote longing for consolatory publication sometimes and not caring sometimes. I wrote to keep my mind off the drawer.

I dove into teaching artist gigs and social services, in large part to keep my mind of the drawer. I blogged with a soldierly intensity, in large part to keep my mind off the drawer. Between her medical missions to Africa, I managed to get my wife pregnant—even this did not take my mind off the drawer.

After reading an excerpt of the manuscript, my friend, the poet Rachel Rose, suggested I send the book to a well-connected poet friend of hers, Peggy Shumaker. With a wince and a glimmer, I did so and got a bittersweet response: hire a professional editor to tear this apart, rewrite it, and she’d deliver it personally to the editor of X press. With trembling fingers, I opened the drawer.

***

Dawn Marano took a few months with the manuscript.

There’s no psychic distance. The narrative and prose are spellbinding, but the reader can’t get in. You’re not letting them. You’re holding Serala possessively. You have to put a present-day narrator on the page or everyone’s going to feel like all these editors that have passed on it—like there’s something so important but you won’t let anyone see it.

In reality the rewrite took me dozens of winter afternoons in an under-heated coffee shop, Seattle scribbled and distorted outside the windows. But in memory it feels like one sitting, like a sigh that went on for months.

Peggy Shumaker forwarded the manuscript to the editor of the scrappy little press. The editor ignored my emails for several months and then passed on my “novel.” By then this felt like little more than an ember alighting on a callus. I found that for the first time since I wrote the first draft, I didn’t care as much about what happened as that I had gotten it right.

“Right” in 2010 looked wildly different from “right” circa 2005. I was no longer a grieving, vodka-smeared, quasi-suicidal romantic. That person had to write the book, but that person was incapable of writing a book that would open itself to strangers. During some fifteen drafts, I’d lose 10,000 words and add as many new ones; I thought I was substantially molding it around a new form each time. But it wasn’t true. For almost five years I’d been moving the camera around me and Serala as we faced one another, believing somehow that the spectacle would be enough for the reader. And for some—friends of ours, Rex, my first agent—it was. But because of Dawn Marano, I finally understood and I turned away from Serala at the end of every chapter and spoke directly into the camera. In 2005 I wrote Serala a letter that I then savaged and mended many times over the next few years. In 2010 I turned it into a book.

Because the editor of X press represented the impetus for this last, determined round, I thanked her—though I corrected her on the genre of my work with a gentle backhand. Chastened, she dropped me a line, still declining, but for new reasons (I don’t think she ever read it). But she did suggest that I contact a young agent she’d recently met who just might be perfect. I surprised her by guessing his name before she could utter it—I wasn’t even surprised.

“There are no straight lines in this business,” Rex told me a week later. “Can we try again? I’ve now read your book more than any other I’ve ever worked on (five times over six years?) and I still love it. More, even. I’m confident I can place it.”

About six months later, he called. An editor at ECW Press in Toronto had fallen hard for the manuscript, much like Rex himself had back in 2005. The advance would be modest, he admitted, as if I cared. But the book had landed in the hands of someone who felt it.

Dear Rex:

I’m glad to be able to finally get something like an initial offer out for you and Eli…. But I want you both to know, no matter what happens, that I truly love this book. I’m haunted by it, and honestly, I’m kinda in awe. Now. Still.

To get it into enough folks’ hands we’re going to have to be creative in how we market it, and we’re going to have to get Eli as involved as possible—talking about it to anyone who’ll listen.

And then, hopefully, a couple great reviews. And then good word of mouth….

And finally, again hopefully, it really takes off.

It deserves nothing less.

I wish I could offer the moon, Rex, but this really is fuzzy and uncharted territory for ECW. I honestly don’t know how the book will do—all I know is that it has to be done.

Through six years, fifty-odd rejections, and sixteen drafts, that’s all I knew, too.

Well I love the title, just love it, and if I saw it on the table in the bookstore, the title would make me pick up the book and look through it and decide. But having read this back story, I will of course buy your book and read it, how could I not? Wow. Congratulations.

My favorite line: “That person had to write the book, but that person was incapable of writing a book that would open itself to strangers.”

This courage is what will sell the book you’ve written. This is what I will love when I read it. Carry on Eli. You rock.

This is lovely, Eli. And a very long time coming. I am so proud of you – and relieved on your (and her) behalf.

what a ride. way to persevere!

You convinced me! xx.