A Talk with Jack Loeffler (And Another Talk this Coming Wednesday)

categories: Cocktail Hour

3 comments

Next Wednesday night I’ll be at Collected Works in Santa Fe at 6pm. It’s a long drive so we are starting tomorrow (Sunday) morning so we get there on time!

Next Wednesday night I’ll be at Collected Works in Santa Fe at 6pm. It’s a long drive so we are starting tomorrow (Sunday) morning so we get there on time!

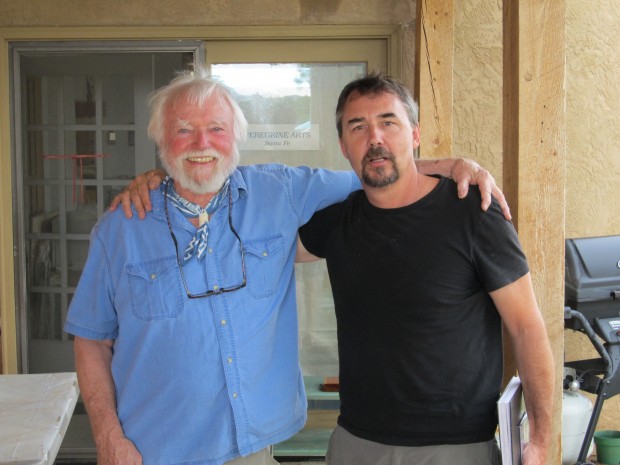

I will be introduced by, and in conversation with, Jack Loeffler, one of Edward Abbey’s closest friends. Loeffler lives in the hills outside of Santa Fe,and when I was traveling for the book my friend Mark Honerkamp and I dropped by and spoke with Loeffler in the open, book-filled study of his single-story adobe home. (These are the pictures Mark took while we spoke.)

“What Ed and I knew, on some fundamental level, is that once you’ve been out in it long enough, it becomes the top priority,” he told us as we settled into the study. “When you’re out in it fully, you recognize it’s where you belong. We concluded that it took a good ten days in the wilderness. Until you began to change. You need to live in the spirit of nature, so that it’s totally and intuitively in your system. Then you don’t have any choice but to defend it.”

A handsome, fit 74 year old man with a big smile and white beard, Loeffler was innately theatrical. He wore an open Western shirt, kerchief and khaki shorts. His whole demeanor was what I can only describe as oddly joyful.

“Ed was a tortured man,” he told us at one point. “He was no stranger to despair.”

“Ed was a tortured man,” he told us at one point. “He was no stranger to despair.”

That jibed with what I had read and thought. Though Loeffller spoke those melancholic words with a beaming smile.

“I think that is one of the reasons we got along so well,” he continued. “I am a stranger to despair.”

He exploded in a wild burst of a laugh after he said this, a noise we would grow used to by the end of the interview. I can only describe it as being like the upward yodeling of a pileated woodpecker.

I agreed that he seemed to be a sunnier spirit than his friend.

“I’m a happy dude, man,” he said.

I confessed to him that I was feeling guilty about all the driving I had been doing.

“Ed and I drove all over the Southwest,” he said. “And worse we took both of our trucks. I don’t think we had a single trip when we didn’t get stuck. As a matter of fact we even got stuck when he was dead. We had made a vow to each other that whoever went first, the other wouldn’t let them die in a hospital bed. Ed died well but when I went to bury him in the desert, with his body in the back of the truck, we got stuck in the sand. It was inevitable, I guess.”

Dead bodies in the back of the truck were just one way that their camping trips were not like yours or mine. I mentioned this.

“Not only did we take two vehicles much of the time we camped, but we always brought matching .357 Magnums. So we were ready.”

“For what?” I asked.

“Well, I have to be careful here. For Ed the statute of limitations has run out. Not necessarily for me. Let’s just say that one of the reasons we had them—not that I would really use it for this—is that ostensibly a .357 can crack an engine block in a big piece of machinery.”

This was what I wanted to know. How much of Abbey’s monkeywrenching was real, how much legend or fiction? Was he just good with words or did he get his hands dirty?

“Ed did his night work,” Loeffler told me. “It started with cutting down billboards in college. What you’ve got to understand is that rebellion was part of him, in his blood. Look, his father, Paul Revere Abbey, named one of Ed’s brothers William Tell Abbey. Paul had met Eugene Debbs who was a huge influence on him. From his father’s side Ed got that strong, individualistic point of view.”

What became clear to me, as Loeffler kept talking, was that Ed Abbey did a lot more than pay lip service to monkeywrenching. Loefller described the early fights of the Black Mesa Defense Fund and the battles against the Peabody Coal Company.

“We had a rule of three,” he said. They did their work in small groups, preferably two but three at most, and never confided in anyone else about that they’d done.

Both men had come to believe that American culture was “lodged completely in an economically dominated paradigm” and that those who opposed it would be punished.

“Law is created to define and defend the economic system,” Loffler said. But fighting was a moral imperative the two friends came to agree: as obvious a case of self-defense as repelling someone who has broken into your home. That said, they would only push it so far. Abbey and Loefller made vows of nonviolence. Doing harm to machines was one thing, human beings another.

Loeffler believed that too many people underplayed his friend’s belief in anarchy, which Abbey called “democracy taken seriously.” (FN: 26 One Life at as Time Please) Government, any government, should be rightly feared: “Like a bulldozer, government serves the caprice of any man or group who succeeds in seizing the controls” (27) For this reason Abbey was adamantly opposed to any control of guns. (One wonders if recent events might have led to a softening of this position, though softening, as a rule, was not in Abbey’s nature.)

And there is something else in Abbey that Jack Loefller was suggesting we not take lightly. Abbey fought the prevailing power, but he also knew why most people didn’t fight the prevailing power. Comfort was a large part of it. For most of us there is a lot to lose. It was, and is, Abbey’s job to make us feel uncomfortable in our comfort. He wrote: “Never before in history have slaves been so well fed, thoroughly medicated, lavishly entertained—but we are slaves nonetheless.” And this was even before they gave us slaves our cell phones and computers.

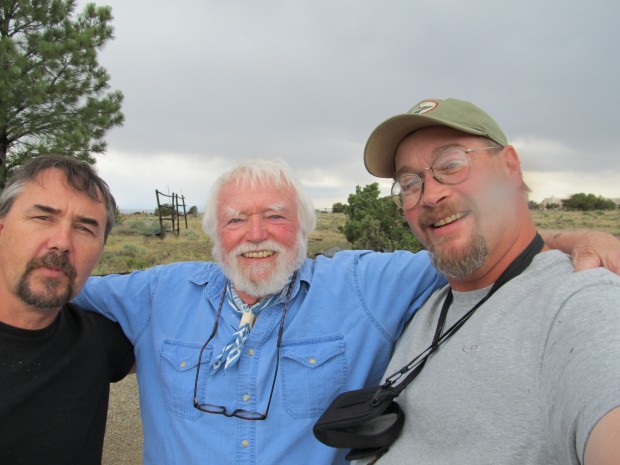

Right before we were ready to say goodbye, a huge crack of thunder got us jumping out of our seats. The rain pounded on the roof, a significant percentage of the rain that Santa Fe would see that year. When it stopped, Jack walked us out to the car. We hugged goodbye, which seemed in no way unnatural.

There was something a little groovy about Jack Loeffler, the kind of grooviness that usually sets my bullshit detector off. But the detector stayed quiet during our visit. If his book had been slightly tone deaf, Jack Loeffler in person was anything but. I was both charmed and impressed by the man. He was a force: voluble, smart, dynamic.

We left reluctantly and when we finally did, after knowing him for three hours, we felt we were leaving a friend.

The last thing he said to me was a directive regarding his own friend, Edward Abbey.

“Bring him alive,” he said as we climbed in the car. “Farewell!”

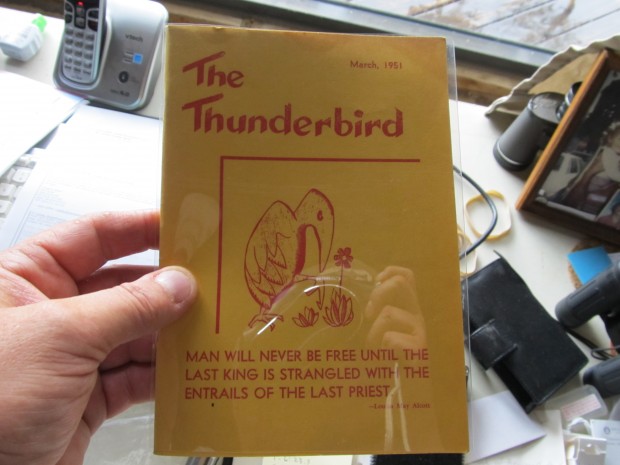

The University of New Mexico magazine Abbey edited.

Old Guys’ Selfie

the visit with Loeffler was one of my favorite passages in the book; this little addendum, similarly enjoyable and enlightening.

You’re driving???

Interesting . Great photos of Dave. Looks in shape for a frisbi match.