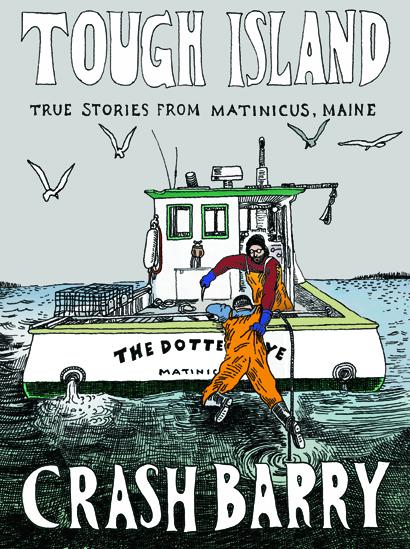

Guest contributor: Crash Barry

Serial Sunday: Crash Barry’s illustrated TOUGH ISLAND, Complete!

categories: Cocktail Hour / Getting Outside / Guest Columns / Reading Under the Influence / Serial Sunday

2 comments

The Complete, Illustrated Tough Island

Chapter One

March 1991

I’d just finished a stint as a sailor in the Coast Guard, fighting the War on Drugs and the War on Haitian Refugees. No money. No job. No leads. A rudderless 23-year-old couch-surfer crossing back and forth over the state line between Portsmouth and Kittery.

Then the message came from a Coastie pal’s wife. Her dad, a lobsterman on Matinicus, Maine’s most remote inhabited island, needed a helper immediately. A sternman. A hired hand. A modern indentured servant paid with 15 percent of the catch, plus free housing, on an island 20 miles out to sea.

I’d been to Matinicus once before, for a weekend the previous fall, to help my Coastie pal paint an apartment in a waterfront building owned by his father-in-law, Captain Donald. We arrived by lobster boat on a foggy night and worked for two foggy days, ate lobster, drank beer and furtively smoked herb. Then the weather cleared and we flew back to the real world of the Coast Guard.

A move to a remote island was appealing, especially following my over-regulated life in the military. During my time as a Coastie, I traveled to exotic locales, where I witnessed the abject poverty, sorrow and injustice that lived beneath the beauty of the landscape. I needed a new place to ponder what I’d seen. And to recover from my time as a hard-drinking, pill-popping, brawling, pot-smoking sailor. Living in my own shack seemed ideal after three years aboard a ship of 80 men. As a young, wanna-be writer, working on a boat was ideal. So was growing long hair and a bushy beard, smoking tons of ganja and ingesting psychedelics while composing sad, epic poetry. Secluded on an island, I’d be able to hear the tide and absorb the wind. Become tougher. Stronger. Purer.

A move to a remote island was appealing, especially following my over-regulated life in the military. During my time as a Coastie, I traveled to exotic locales, where I witnessed the abject poverty, sorrow and injustice that lived beneath the beauty of the landscape. I needed a new place to ponder what I’d seen. And to recover from my time as a hard-drinking, pill-popping, brawling, pot-smoking sailor. Living in my own shack seemed ideal after three years aboard a ship of 80 men. As a young, wanna-be writer, working on a boat was ideal. So was growing long hair and a bushy beard, smoking tons of ganja and ingesting psychedelics while composing sad, epic poetry. Secluded on an island, I’d be able to hear the tide and absorb the wind. Become tougher. Stronger. Purer.

“I’ll withhold the money from your first check. I hope this works out,” whined Mary-Margaret, Donald’s wife, a skinny woman in her mid-sixties. She was 100 percent gray. Her short hair. Her sunken eyes. Her skin. All the color of cigarette ash. Clothes. Aura. Mini-van. All the same dismal hue. “Otherwise, how will you pay me back for all this gear?”

We were at a commercial fishing store in Portsmouth. She bought me three pairs of gloves, a nice suit of Grunden oilclothes and a decent pair of boots. About two hundred bucks with no sales tax, because it was New Hampshire. She bought everything in New Hampshire, she boasted, as we loaded spools of rope and boxes of fasteners into the mini-van.

By the time we crossed the bridge into Maine, I was in hell. The van’s heat wouldn’t shut off, the power windows wouldn’t roll down, and with a captive audience, she didn’t stop talking. Stories exploded out of Mary-Margaret with a frenzy. According to her, the island’s 50-person population consisted mostly of thugs, troublemakers, cheats, liars, lonely women and stupid men. Plus a handful of children and a couple of retarded senior citizens. About a dozen men were lobstering thieves, she said. The exception, of course, was her hero, my new boss, Captain Donald, who could do no wrong.

“You’re not a drunkard are you?” she asked, turning to look at me, a bead of crusted gray spittle caked on both corners of her mouth. “Been lots of shenanigans lately on the island. We don’t need any more drunkards.”

“Nope, I’m a social drinker,” I answered. A smoker. A stoner. A tripper. An occasional snorter of powder and popper of pills. But not a drunkard. I did drink, but I could take or leave booze. Wasn’t one of my real vices. “Never to excess,” I added.

“Donald doesn’t put up with foolishness, so you behave yourself,” she wiggled her forefinger at me, a gray froth sputtering from her colorless lips. “On mornings you go out to haul, you better be ready at five.”

For the rest of the two-and-a-half hour trip, she chattered. She wasn’t from Matinicus. Donald picked her up in East Boston during his tour in the Navy, four decades before. She prattled on about her life on the island. She jumped from topic to topic: Bad neighbors, her children, the high price of everything, the low price of lobster. Occasionally, she paused to breathe, then start again, usually by insulting an enemy or Donald’s brother’s wife.

As we crossed the Rockland town line, she looked at me and smiled. “My daughter says you’re Catholic. That’s wonderful. So am I! The only one on the island.”

“Well, I was raised Catholic, but these days, not so much.”

“She didn’t mention you were lapsed.” She frowned. “Maybe that’s why you were sent here. So I can get you back to church. Remember,” she said brightly, “Catholics can always come home.”

I was suddenly worried. “Does this have anything to do with working for Donald?”

“No,” she groaned. “He’s not Catholic. Doesn’t even wanna hear the word ‘church’.”

We met up with The Dotted Eye at a dock in the Rockland Coast Guard Station. I didn’t bring much because I didn’t own much. A half ounce of seedy marijuana and a carton of Camel Filters. A couple tabs of LSD, a cardboard box of books and a green canvas sea bag packed with 40 pounds of clothes. A sleeping bag, a quilt my mother had made, a typewriter, a clock radio and a box of Red Rose tea. Captain Donald shook my hand and grunted as I climbed aboard the boat for the first time. In his mid-sixties, he looked like a caricature of a Maine lobsterman. Salt and pepper beard with no mustache. Arms the size of legs. Legs the size of trees. Hands of a giant.

We met up with The Dotted Eye at a dock in the Rockland Coast Guard Station. I didn’t bring much because I didn’t own much. A half ounce of seedy marijuana and a carton of Camel Filters. A couple tabs of LSD, a cardboard box of books and a green canvas sea bag packed with 40 pounds of clothes. A sleeping bag, a quilt my mother had made, a typewriter, a clock radio and a box of Red Rose tea. Captain Donald shook my hand and grunted as I climbed aboard the boat for the first time. In his mid-sixties, he looked like a caricature of a Maine lobsterman. Salt and pepper beard with no mustache. Arms the size of legs. Legs the size of trees. Hands of a giant.

When we reached the other side of the breakwater, he opened up The Dotted Eye. She was super-fast, for a work boat. “I used to race her,” he said over the roar and chortle of the diesel, a big grin on his face and a glint in his eye. “Used to win.”

“NOT ANYMORE,” Mary-Margaret shouted. “PRICE OF FUEL IS TOO HIGH!”

***

“See the island?” Captain Donald pointed to the distant horizon. We’d been cruising for ten minutes. “Steer towards it. I’m gonna catch a little snooze.”

I didn’t see the island, but took the wheel anyway, noted the compass course and kept her steady, an easy task for a salty old helmsman like me. (I’d spent countless hours behind the big wheel of my Coast Guard cutter.) Donald layed on the engine box and closed his eyes. Mary-Margaret leaned against the wall in the corner of the cabin, looking even grayer than in the van. Her pallor told me she was seasick. Saw a lot of that in the Coast Guard. Many shipmates fell victim to motion sickness. Luckily the giant rolling swells and troughs of Caribbean hurricanes and the choppy seas of North Atlantic gales didn’t bother me, allegedly due to an inner-ear imbalance. On land, I was clumsy and crashed into doorways and tripped over carpet. On the open ocean, however, I danced with waves.

Life was looking up. A paying job. A place to live. A new world to explore. I felt awesome and powerful. No idea where I was going, but driving The Dotted Eye was such a pleasure, I didn’t care. We flew through the quintessential Maine seascape of lighthouses, lobster buoys, sea gulls and kelp-covered ledges. We arrived at the Steamboat Wharf about an hour and a quarter after we left Rockland. The tide was almost high, which made it easy to unload. We put the groceries, fishing supplies and all my earthly possessions in the back of Donald’s beat-up and rusted Chevy.

“Be sure to get lobsters,” Mary-Margaret reminded Donald as she climbed into the passenger side of the truck. “We’re having lobsters, potato salad and lemon cookies for dinner.”

Donald grunted as The Dotted Eye backed away from the wharf, came about, then headed the 500 feet to his mooring near the breakwater. We jumped into his skiff and zipped over to a good-sized barge, lined with stacks of traps and a couple huge bait boxes.

“Get up on the scow,” Donald ordered. “And grab that crate.” He pointed to a rope attached to a box floating in the harbor. “Haul it up on deck.”

I pulled the heavy box onto the scow and water spilled out through the spaces between the box’s wood slats. Donald handed me a plastic bag.

“Pick out your suppah,” he said. “And let’s be friggin’ quick about it.”

I knelt on the scow and opened the crate. It was filled to the brim with delicious crustaceans.

“How many?” I asked.

“One for me and one for her,” he said. “And as many as you want. C’mon. We don’t have all night.”

Unlimited lobster! That’s a job perk I hadn’t considered. I picked out two big ones, for them, then three huge crustaceans for me. Donald didn’t bat an eye. I tied the crate shut and pushed it overboard.

Don’t Drink The Water

“Showers cost lots of money out here,” Mary-Margaret complained. “Running the water pump doesn’t come cheap, because our electricity is the most expensive in all of Maine.” She poured us each a glass of red beverage. “This is sugar-free Kool Aid. Because of Donald’s diabetes. Cherry is his favorite.”

I watched him wince as he took a sip of the awful stuff. I had learned from his daughter that Donald used to be a major-league boozehound who smoked two packs of Winstons a day. About a year prior to me getting hired, the doctors said no booze, except for a single monthly ration of scotch to keep him from going absolutely crazy. And no cigarettes. A big deal for a guy who’d been smoking since he dropped out of school at age ten.

“Why is the electricity so expensive?” I asked, happy to have a trio of good-sized lobsters on the plate in front of me. No butter, though. Captain Donald couldn’t have butter because of his strict diet. That meant no one had butter. “Where’s the power come from?”

“We didn’t have power when I was growin’ up,” Donald snorted. “Didn’t need it, neither. Weren’t until 1976 we got power lines strung.”

“I, for one, am glad we have electricity,” Mary-Margaret interrupted. “I just wish it wasn’t so darn expensive.”

“And the price is only gonna go up,” he cackled and shook his head as he cracked a claw. “ ‘Cuz we’re running a big diesel power plant to make electricity non-stop. And the price of fuel ain’t never going down.”

“Running the water pump doesn’t come cheap,” she said, repeating her mantra. “That’s why you can only take a short shower. Set the timer that’s on the toilet. No longer than four minutes.” Mary-Margaret grunted. “We don’t take long showers around here.”

After supper, eager to wash off the grime from the road and boat trip, I took a shower and dutifully set the timer. I didn’t need all four minutes. The water smelled and tasted unpleasantly of kerosene. So I quickly washed and rinsed, then dried with a towel that also had a petro-odor. I was clean, but felt oily.

The first night, I stayed in their guest room. (They lived in a non-descript house in the middle of the island, with a dull backyard view of scraggly woods and a front window that overlooked the road to the airport.) After hauling traps in the morning, Donald was gonna bring me to my new home on the shore. The bed sheets and pillow case smelled like kerosene, but it didn’t stop me from sleeping soundly.

Four-thirty a.m. came quick. I was awake and ready instantly, thanks to my rigorous Coast Guard regime of pre-dawn drug boardings and search-and-rescues. Donald and I drank a cup of tea and ate toast with margarine, then headed to the shore in his beat-up Chevy. It was still dark as we climbed down a ladder attached to the Steamboat Wharf and into his 14-foot aluminum skiff powered by a 10-horse outboard. He stood in the stern and motored us to the mooring. Other men were also en route to their boats. And a couple were already steaming out of the harbor into the dawn. Donald didn’t wave or acknowledge any of them. They ignored him back.

Aboard The Dotted Eye, we pulled on our oil clothes, boots and gloves. Donald started the boat, then showed me the way he wanted the bait bags filled. Six fish per bag, more or less, depending on the size. He showed me how to attach the wash-down hose to the lobster holding tank. And how to use the banding pliers. Then he told me to release the mooring and we were underway.

Standing on the bow, I inhaled deeply and tasted the mix of salt air, rotten bait and diesel. As Donald headed past the breakwater and bell buoy, I absorbed the amazing early pink light and energy reflecting from the sky and sea. I was glowing. Vibrating positively. Joyful. In the zone of happiness, reveling in the scene and the scenery. I felt so lucky and happy. To be alive. To be working on a boat. To be living in Maine.

“WHADDYA DOIN’?” Donald shouted over the din of the engine and gestured for me to join him in the cuddy. “You better fill as many bait bags as ya can,” he barked and pointed sternly. No smile. No glint in his eyes. “ ‘Cuz we’ll be at the first string in five minutes.”

By noon, we were done hauling and tied up at the bait scow. Donald decided to go easy on the new guy and only haul 100 traps. He usually hauled 250 to 300 a day. From a huge bin on the scow, I shoveled herring and refilled the bait box, then washed and scrubbed the boat while Donald dealt with the lobsters.

I knew I could handle being a sternman. Not a hard gig, especially for a fella who could roll with the rhythm of the sea. Easier than being a deckhand on a Coast Guard cutter, that’s for sure. All morning, I filled bait bags, emptied traps of various fish and underwater fauna, while measuring and banding lobsters. My forearms were greasy with fish guts and my hips were black and blue from slinging traps port to starboard, but it was simple work.

“After bait and fuel, I’d guess you made about fifty bucks,” he drawled as we slid a couple wooden crates filled with lobsters into the drink. Donald tied them off to a cleat on the scow. “Whaddya think? Can you do the job?”

“Yes sir!” I said. At the moment, flat broke, fifty bucks was a fortune. Even though the first $200 was paying for my new gear, I knew it wouldn’t be long before I’d need a bank account. “No problem.”

“All right then.” Donald looked at his watch. “Time to go home and have a lousy sandwich.” He coughed and spit into the harbor. “Then we’ll move you to your room.” He spit again. “I’ll tell ya, I’m getting sick of friggin’ turkey bologna.”

Up at the house, in the center of the kitchen table, was a pitcher of the red beverage, three glasses and a bowl of potato salad. Mary-Margaret was busy at the counter. I couldn’t stomach the Kool Aid again, so I grabbed a cup and headed for the sink.

“Be sure to take it from the filtered spigot,” she said, as she placed sandwiches on plates. “The one on the right.”

“Something the matter with the water?” I asked.

“Years ago we had a kerosene spill and it tainted the aquifer,” she explained. “Been ten years and the well hasn’t been the same since.”

“Twenty,” Donald grumbled, pouring himself a glass of Kool Aid. “Twenty years ago.”

“Really?” Mary-Margaret said. “Seems like yesterday. Anyways, 500 gallons of kerosene from the…”

“By Jeezus!” he interrupted. “Mary-Margaret, you’re numb as a hake. How could it be 500 gallons? Our tank only holds 250.” He grunted and spit into his handkerchief. “It was 250 gallons. Besides, there ain’t nothing wrong with the water no more.”

“If you say so, dear.” She nodded and sighed. “Still, we only drink from the filtered spigot.” She smiled feebly. “How’s your sandwich?”

“Great,” I said, even though the turkey bologna on store-bought bread with light mayo and runny yellow mustard was dreadfully bland. “I was starving.”

“You only worked half a day,” she snorted, “can’t be too hungry.”

“I got a surprise for ya.” Donald grinned. His mood seemed to improve after lunch. “I like my sternman to have transportation.” He led me out to a shed in the backyard and slid the door open to reveal a motorcycle. “As long as you’re on the island, working for me, the Hondamatic is yours. One of the perks of the job.”

“Wow.” I had zero interest in motorcycles. My only experience on a bike resulted in a parking lot crash back when I was a Coastie. Pedal power was more my style. “You know, uhhhh,” I stalled. “I really don’t have much luck with motorcycles.”

“Easiest bike in the world to ride,” he assured me. “It’s a Hondamatic. No clutch. Two speeds. Bought it new in ‘78 and it ain’t never been off Matinicus since.”

“Well,” I said. “It’s just that I’m kinda…”

“Jeezus, boy, my granddaughter’s 12 and she loves this bike,” he patted the saddle. “Take her out. Go nice and easy. Look around. Get a feel for the place.”

After driving back and forth in front of Donald’s house ten times, I was ready to go. I rode down to the harbor and took the road out to Markey’s Beach, where I parked and walked the length of it. The tide was halfway to high and the surf broke gently on exposed ledges. I had the entire place to myself, except for a few seagulls frolicking on the wet sand.

After driving back and forth in front of Donald’s house ten times, I was ready to go. I rode down to the harbor and took the road out to Markey’s Beach, where I parked and walked the length of it. The tide was halfway to high and the surf broke gently on exposed ledges. I had the entire place to myself, except for a few seagulls frolicking on the wet sand.

After a couple smokes, I drove back to the harbor and parked by the post office, which shared a building with the lone island store. Both were closed. I peered through the windows. Seemed the stock consisted mostly of beer, soda and bags of snack food. The rest of the shelves looked barren.

I wandered over to the end of the Steamboat Wharf to get a good look at the harbor: A rugged little village of brightly painted fishhouses and wharves, mixed with a couple derelict buildings, crumbling, dark and forgotten. A charming postcard.

There was an old-timey telephone booth in front of the post office, so I decided to give my folks back in western Massachusetts a jingle because they had no idea where I was. The answering machine picked up.

“Hi, Mom and Dad, it’s Crash calling.” I paused, trying to think of an accurate way to describe my new situation. “Everything’s great. I got a job on this island in Maine called Matinicus. You can find it on the map. It’s 20 miles off of Rockland.” I paused again. “I made 50 bucks lobstering today, plus all the lobster I could eat.” Both of my parents loved lobster. They’d appreciate the detail. “And I just cruised the island on my new motorcycle. Pretty exciting. I’ll call you again, soon. As soon as I get settled.”

Back on the bike, I zipped up to the middle of the island and took a left at the crossroads, rode past the modern one-room school house and the cemetery of old stones and collapsed graves. Then I turned onto a grassy trail framed by spruce trees that seemed to follow the shoreline to the south. Glimpses of the shimmering sea beckoned me and a long path of sunshine created a sparkling trail six miles out to Matinicus Rock’s infamous lighthouse.

I crept along on my motorcycle, admired the amazing view, breathed deeply the open ocean air and reveled in my good fortune. Perhaps I drove too slow. Or maybe I shouldn’t have taken the Hondamatic off the road. No matter. Suddenly the bike slid and toppled over, pinning me on a hillside sloped toward the rocky shore. Stunned and frightened, but uninjured because the bike was surprisingly light, I squirmed out and vowed to never ride a motorcycle again.

Donald shook his head when I told him what happened. “You’re being stupid,” he said. “You shouldn’t have gone on that trail. Stay on the road and you’ll be fine. It’s a friggin’ road bike for christ’s sake.”

“Well,” I said, eager to forget the incident. “I still think I’d prefer to walk.”

“Suit yourself.” He rolled the bike back into the shed. “Your loss.”

We took Captain Donald’s truck down to the shore so I could move into my new pad. We parked by the post office and I followed Donald on the foot path that wound around the edge of the harbor, through the village of fishhouses. I thought we were headed to the apartment that overlooked Donald’s wharf, the one I painted the autumn before, a nice one-bedroom with a sawdust toilet and a full kitchen, sans running water.

Instead, he brought me to another building, ramshackle and rickety. The first floor was garage-like, filled with ancient coils of used pot warp, tow lines, fishing net, broken buoys, and miscellaneous junk. We climbed a shaky exterior staircase to his shop on the second floor. The room was about 20-foot square. The floors and walls were splattered with orange and white. Freshly painted buoys of the same colors hung from the ceiling, making it mandatory to stoop and duck to walk across the room. We passed the tiny wood stove and came to another doorway.

“Your new home.” He grinned. Tough to tell if his smile was genuine or evil. “Hope you like it.”

The back room was ten feet wide and twice as long. But not cozy. Or comfortable. Or rustic. Or charming. The walls were fake wood paneling. The floor was particle board. A bare bulb hung from the center of the ceiling. In daylight, it was easy to see the layer of dust on the single wooden chair, small table, nightstand and unmade cot that filled most of the space. An ersatz kitchen – consisting of a dorm fridge, a two-burner gas stove and dishpan – occupied the rest. The east wall had a trio of windows that overlooked the harbor.

Wasn’t much of a room, but better than a berth on a ship, a mat in a homeless shelter or a bunk in a prison cell. And it did have a great view. “Doesn’t seem to have a door,” I said.

“This is the door,” he said, tugging on a blue tarp attached to the wall on the shop side. “Just hook the grommets on the nails and you’ll be all set,” he said. “Though I wouldn’t do that if you got the wood stove going.” He grunted. “Tarp will keep the heat out.”

“Oh,” I said. “What about a bathroom?”

“Hah,” he said. “See that?” He pointed at what looked like a green plastic ottoman. “Pull the cover off and it’s a toilet. But only use it in emergencies, ‘cuz it’s a sonofabitch to clean. Don’t worry, you’ve got an outhouse too,” he said. “Follow me.”

At the end of his wharf was an ancient shed. He pulled the door open. “In there,” he said. “Just like in the olden days. Hah!”

The shed was packed full of old nets and 55 gallon drums of diesel fuel. In the corner was a toilet seat on a wooden box. A classic one-holer. I lifted the seat cover and peered down. I felt a whisper of wind rising from under the wharf. I saw piles of shit clinging to the wharf’s cross braces.

“You share the toilet with my brother’s sternman,” he pointed to another building on the wharf. “That’s where Jimmy lives, but I think he’s in Rockland today.” He coughed and spit into the harbor. “Let’s go have some suppah.”

*

“I thought I’d be staying down in that apartment we painted last fall,” I told Donald while waiting for Mary-Margaret to serve the meal. He drank his red drink. I had water. The kitchen smelled deliciously of the chopped onions cooking atop the store-bought frozen pizza. I was starving and the smell was driving me crazy. “Didn’t think I’d be living in the shop.”

“Whatever gave you that idea?” Mary-Margaret harrumphed. “That’s a rental apartment. For tourists. Way too nice for just a sternman.”

“Wanting the Taj Mahal, are ya?” Donald asked. “Not gonna get it, ‘round here.”

They both chortled until their laughs turned into groans.

After supper, I walked to my new home carrying my sleeping bag, some borrowed sheets and a roll of toilet paper. The night was star-filled and quiet. No moon. No clouds. No wind. As I neared the shore, I heard the occasional clang of a bell buoy and the gentle hum of the island generator in the background. Didn’t see another person. Felt like I was the only human on the island. A good feeling.

After supper, I walked to my new home carrying my sleeping bag, some borrowed sheets and a roll of toilet paper. The night was star-filled and quiet. No moon. No clouds. No wind. As I neared the shore, I heard the occasional clang of a bell buoy and the gentle hum of the island generator in the background. Didn’t see another person. Felt like I was the only human on the island. A good feeling.

My room smelled of old rope, salt and bait, though it could have been my personal odor since I hadn’t showered after hauling. I found bits and bones of herring in my hair and beard. Under the bare bulb, I smoked a joint and examined my new place. It was filthy, with signs of mice, but totally functional.

An unexpected bonus was the sound of the tide lapping at the wharf. As the tide rose, the ocean stretched and flowed beneath the building. The thought of sleeping above water calmed me.

I made the bed and set my alarm for 4:30 and hit the soft and springy cot. Tired in a good way and excited to have my own pad, I was content for the first time in a long while.

In the dark, I turned on the radio and scanned the FM dial and was happy to discover many frequencies came in loud and clear. I switched to the AM band and found even more stations, some as far away as Philadelphia and Quebec. I’d been a serious radio listener since I was a little boy. Pleased, I tuned to WOR in New York City, dozed off and slept soundly.

*

For the next two years, I lived on this beautiful island located in the center of the richest lobster grounds in the world. Despite its remoteness, Matinicus was a microcosm of modern American society. Ruled by gossip and slander. Rife with substance abuse and marital discord. Over time, the archetypes revealed themselves: The angel, the hero, the loner, drunk, the cheater, the molester, the abuser, the thief, the suicide and the killer.

Through the eyes of some, Matinicus was an outlaw’s paradise where hardened souls could lurk in the shadows of fishhouses and wharves, far from the watchful police state.

For other islanders, Matinicus was a protected homeport and an idyllic place to raise a family. An outpost where independence was necessary and honored, but where working with others – even sworn enemies – was occasionally required to save a life or livelihood. A world of heavy winds and violent storms, where fervent sunrises and fiery sunsets painted forests, meadows, beaches and ledge with vibrant colors. Except when it was foggy. Which was quite often from June to October.

Two years living in a fish shack didn’t make me an expert on Matinicus. But it was a long enough immersion to recognize the distinctive nature of the island. To see beyond the myth and hype. To study a unique society with a wanna-be writer’s brain, filtered through a thick lens of drugs, youth and hard work.

Island Justice

Ever since the first white settler, Ebenezer Hall, a notorious thief and scoundrel, got scalped in 1757 by the local Indians who owned Matinicus, a mist of violence has loomed like low hanging fog, enshrouding the island in a bad reputation. Mostly because of a few loud, bad apples. Stabbings. Arson. Fisticuffs. Sucker punches. Cold-cockings. Ass-kickings. Home invasions and destruction. Murderous threats and name-calling. Guns aimed. Shots fired. People wounded. All part of island history and lore.

No cops were ever stationed on Matinicus, where the only law officer was the constable – elected anew each year – an island resident without training whose only role was to occasionally deal with the mainland cops who came out to make a drug bust or issue a summons. There was no cop, that is, until Jerold Day offered his services to the Knox County Sheriff’s Department.

Jerold Day moved to the island the year before I did. His only link to Matinicus was his brother, a lobsterman, who had married an island girl. Jerold Day had zero experience in law enforcement. A fundamentalist, teetotaling Christian who believed the schoolteacher was in league with the devil, his resume stretched through several states and industries, reeking of a loser who couldn’t keep a job.

None of that mattered to the macho sheriff in Rockland who was desperate to tame Matinicus and wanted to prove to the rest of mid-coast Maine that his law was stronger than the island’s anarchy. At the beginning of March, the sheriff gave Jerold Day a badge, gun and a blessing. And Jerold Day was transformed from a dubbah to a deputy.

Four drunk sternmen, pissed that a cop was suddenly messing with their paradise, decided to fuck with the deputy. Sternmen, by nature, are rugged and beefy. A team of four are almost all-powerful. Under the cover of darkness, they walked to the deputy’s house and easily flipped his truck onto its side.

The sternmen didn’t know the deputy was waiting in the shadows. They also weren’t aware of the motion-sensitive spotlight he installed on his house. (The first on the island.) When the truck tipped over, the light got triggered and the deputy saw them all: Billy, Bobby, Buddy and Alex.

The deputy drew his gun and fired a shot in the air.

The three Bs scattered and escaped. Alex wasn’t so lucky. Startled by the shot, he froze for a split second, which gave the deputy just enough time to pistol-whip him from behind. He brought his gun down hard on Alex’s head. Knocked him out and split his skull open. Then the deputy cuffed and dragged the unconscious man across the yard, opened the bulkhead, lugged him down the stairs and handcuffed him to a pole in the center of the cellar.

Meanwhile, the other fellas had regrouped in a harborside fishhouse, wondering what happened to Alex. Probably a good thing they didn’t know he was captive in the deputy’s basement and that mainland cops were en route to the island aboard a 41-footer from the Coast Guard station, ‘cuz that could have started an all-out shooting war and raid of the deputy’s house to save their pal. Instead, they got drunk and high on their bottle of rum and good bag of weed, thinking Alex went home to bed.

An hour and a half later, it was nearly low tide and they saw the Coast Guard boat slowly creeping around the breakwater. The sternmen wondered why the Coasties were coming to Matinicus. Was someone sick?

“Jeezum crow,” one of the fellas said, “those guys are gonna hit the Indian Ledge if they ain’t careful.”

The three sternmen jumped into a skiff and raced out to the Coast Guard vessel, leading them around the ledge and up to the Steamboat Wharf. Unbeknownst to the sternmen, the deputy had borrowed his brother’s truck and was on his way to the wharf with Alex, bloody and hogtied, in the back. The deputy arrived just as the cops disembarked and climbed the ladder.

Pandemonium erupted as the sternmen realized what was going down. The deputy told the other cops to arrest the three Bs. The island foursome, at gunpoint, were ordered onto the Coast Guard boat, where they were cuffed, read their rights, then brought ashore to spend the night in the Knox County Jail.

“Gonna get that asshole,” Alex said on a stormy night two weeks later, his head wound still sporting a bandage. We were playing cards, smoking herb and drinking whiskey in his shack. “Gonna get him good.”

“How?” I asked.

“You’ll see,” he said, picking up the axe leaning against the wall. “You’ll see,” he repeated, then opened the door and headed into the screeching wind.

The next morning, at dawn, Donald and I were aboard The Dotted Eye, getting ready for a long day of hauling traps, when he spotted the deputy’s 20-foot lobster boat aground on a nearby ledge, sitting high and dry with a hole in her hull.

I imagined Alex in a skiff, cutting the mooring, maybe giving the boat a little push towards shore. Whacking at it, once or twice, with the axe, knowing there was no chance he’d get caught. No evidence to be left behind. No witnesses. And since nearly everyone on Matinicus hated the deputy, the list of suspects would be long. This was the start of the concerted effort to get rid of the deputy.

Turns out there was always law on Matinicus, just not the sort that wore a badge.

They Did Not Shoot the Deputy

Deputy Jerold Day got run off the island on a beautiful spring day, about a month after the pistol-whipping. Since attacking Alex, he’d gotten the cold shoulder from every islander. No one waved at him on the road or acknowledged him at the post office or the store. His kids – a pair of goofy, home-schooled teenage boys – were cruelly mocked and taunted. The worst harassment, however, occurred under the cover of darkness. Someone poisoned the deputy’s geese and threw a bucket of black oil paint on his white truck. Rumors circulated of shots being fired at his house, but no bullet holes were visible.

Everyone knew the deputy was leaving on the next ferry. The sheriff had decided not to replace him. The short-lived law enforcement experiment was over. The deputy spent his last week on Matinicus packing boxes and nailing big sheets of plywood, painted day-glo orange, over his windows, turning his blue house into a tantalizing target for potential drive-bys. His wife and kids had already left, taking the mail plane to the mainland to find a new place to live.

On the morning of the ferry’s visit, a bunch of us gathered for a going-away party at Benny and Paul’s fishhouse, which had a bird’s eye view of the Steamboat Wharf, a couple hundred feet away. The guest of honor, of course, was not invited due to the weed and booze. He was busy, anyway. When the ferry arrived, minutes before high tide, the deputy jumped aboard and climbed into the cab of a large U-haul, first in line for disembarking. When the ramp came down, the truck raced off. His wife and kids, who’d taken the ferry from Rockland, were crammed in the front seat alongside him. The truck bounced and sped to their house in the center of the island.

On the morning of the ferry’s visit, a bunch of us gathered for a going-away party at Benny and Paul’s fishhouse, which had a bird’s eye view of the Steamboat Wharf, a couple hundred feet away. The guest of honor, of course, was not invited due to the weed and booze. He was busy, anyway. When the ferry arrived, minutes before high tide, the deputy jumped aboard and climbed into the cab of a large U-haul, first in line for disembarking. When the ramp came down, the truck raced off. His wife and kids, who’d taken the ferry from Rockland, were crammed in the front seat alongside him. The truck bounced and sped to their house in the center of the island.

“Better hurry, you sonofabitch, better hurry,” slurred Brenda, Alex’s 40-year-old mom, already three-quarters drunk on coffee brandy. “Less than an hour to pack that big friggin’ truck.” She laughed. “Tides and ferry don’t wait for nobody.”

“I almost hope the bastard misses the boat,” said Pierre, Alex’s step dad. “Jeezum Christ, imagine the friggin’ late fees if that truck stays on the island for an extra month.” The ferry visited Matinicus monthly, except during the three darkest months of winter, when it didn’t come at all.

“I just want the motherfucker gone,” Brenda said, shaking her head. “Asshole.”

The party continued. We all drank and smoked and got higher and higher, watching the ferry, wondering if the Deputy was gonna return in time. He made it with a couple minutes to spare. The whole family climbed out of the truck and lined up against a gunwale for a final look at the island. Standing on Benny and Paul’s roof deck, I watched them through binoculars. I could see the relief on their faces.

The party grew louder and louder. There was raucous hooting as Brenda and Pierre unfurled a banner. Pierre, in his role as a selectman, called assessors on the island, had the only personal computer on Matinicus; the banner was made with a dot-matrix printer on an eight-foot-long piece of tractor-fed paper. It read: “Fuck you, Jerold Day!”

“Fuck you, Jerold Day!” the crowd screamed in unison. “Jerold Day, FUCK YOU!” A song, almost.

I took another look at the deputy and his family through the binocs. They seemed puzzled. From their vantage point, the banner was too puny to read. They couldn’t see the many middle fingers, or the lone moon from a fat, drunk islander, either. And the rumble of the ferry’s diesel engines muted our chant.

The ferry left and the party broke up soon after. Not even noon and everybody was hammered. Now that the deputy was gone, the buzz seemed wasted and anticlimactic. And while Matinicus was cleared of cops, it wasn’t like all hell broke loose. Just no one gave a damn about herb or drunk driving or car registrations. The summer came without a bit of drama.

The police stayed away. Word was, they were scared.

Ironically, many years later, Alex purchased the house where the deputy pistol-whipped him.

Not a Cougar, a Lioness

She may have been tall or short. Zaftig or junkie-rail-thin. A blonde, a brunette, a redhead or raven-haired. Doesn’t matter. I’m not gonna describe her, other than to tell you her skin was soft. And she was another man’s wife.

Uninvited, she climbed the stairs to the second floor of the fishhouse and walked right into my room. She introduced herself with a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a fat joint in the other. Didn’t take long for her mission to become clear. She was there to have sex with me.

I’d been living on the island for two months, and my only pals were a half-dozen other sternmen. Married island women, in their role as other men’s wives, seemed blurry and distant. Truthfully, I hadn’t noticed her before. But she certainly got my attention. Quick.

For the next couple weeks, we dallied in weird places at strange times of day. She was hungry and a little freaky. Happy with action, I aimed to please.

For the next couple weeks, we dallied in weird places at strange times of day. She was hungry and a little freaky. Happy with action, I aimed to please.

Then one day her husband went to the mainland (according to her, to visit his girlfriend) for the night. We had the house to ourselves and she was dressed by Frederick’s of Hollywood. After a long bath in scented water, she made love to me on satin sheets, which, in my opinion, were too slippery.

Then she prepared a fine feast. A nice salad. Lobster stew and biscuits. Steaks on the grill. Steamed spinach. Baked potatoes with sour cream. Sex for dessert.

Afterwards, we lounged, naked, on her marital bed with another whiskey and one more joint. She cuddled and sighed. Content. By 9 p.m., my drink was gone. Time to leave. It was the middle of the night, by my Matinicus clock.

“This was great,” I said, trying to figure out how to extricate my arm and unwrap from her embrace without disturbing her comfort. “But it’s late and I better get going.”

“Don’t be silly,” she murmured and snuggled. “You can sleep here. I told you, he’s gone until tomorrow morning.”

Couldn’t take that chance, of course. And besides, I’d never reach deep slumber there. My restless psyche would awake with every creaking board and whisper of wind. I knew the early return of her husband would mean my certain death at his hands.

It’s one thing sleeping with a fella’s wife. It’s another, spending the night in his bed.

“I can’t,” I said, perhaps a little too forcefully. “I need to go.”

She pulled me closer.

“You have to stay,” she said, slowly, stressing each word. “I cooked you dinner. We made love. Twice. You can’t leave.”

Clearly, she wasn’t gonna listen to my rationale. I sat up and swung my legs toward the floor. Her arms were still wrapped around my torso.

“Don’t go,” she said, releasing me only when I got on my feet. “You better not. I’m warning you.”

I pulled on my boxers and jeans.

“If you leave,” she said, her voice growing harder, “we’re never gonna have sex again.”

My silent answer was to button my shirt and sit on the foot of the bed to don shoes and socks. Then I stood again. She pointed at me, her cheeks trembled and her eyes went wide.

“WE’RE THROUGH!” she screamed. “YOU SON-OF-A-BITCH!”

She grabbed my empty whiskey glass from the nightstand and threw it at me. I easily sidestepped. Thud, against the wall. Next came a flying book.

I headed downstairs and she followed, switching tactics. Pleading. Begging. Promising. She’d get up extra early and cook bacon and eggs before I went out to haul.

“Just don’t leave,” she sobbed. “Please don’t leave.”

I ignored the tempting breakfast offer and dashed for the door and into the night.

On the path back to my shack on the shore, it felt like someone was watching me. I stopped, turned, listened and looked around. Dozens and dozens of pairs of eyes glared at me from the darkness of the scrub pines. Cats. Feral cats. The island was overrun with ’em.

Spring Cleaning

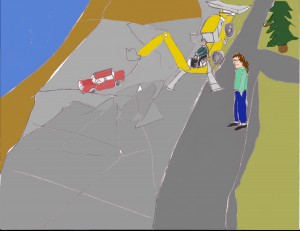

The tide was halfway to high when I drove The Dotted Eye toward the dock and nearly crashed into a Volkswagen bus. I threw her in reverse and backed down hard. Donald, who’d been astern and was almost thrown to the deck, came running forward.

“WHAT THE HELL?” he hollered. Then he spotted the VW parked 10 feet in front of his wharf, the rising sea lapping at the driver’s side-view mirror. “What the frig?”

Turns out Pierre, the upstanding island official, finally decided to clean up his dooryard, which meant getting rid of the VW bus that hadn’t run in a decade and had been cannibalized for all usable parts. Pierre wasn’t gonna pay a hundred bucks to ship the vehicle on the ferry to be junked on the mainland. He got rid of it the island way.

Unbeknownst to us, earlier in the day, at low tide, with help from his pals, Pierre had pushed and pulled and rolled the bus down the beach. He hadn’t intended to leave it in front of Donald’s wharf, he claimed. The bus got stuck in the mud and mussels, Pierre said. So he’d lashed an old hawser, with a buoy on the end, around the VW, and called it good.

Unbeknownst to us, earlier in the day, at low tide, with help from his pals, Pierre had pushed and pulled and rolled the bus down the beach. He hadn’t intended to leave it in front of Donald’s wharf, he claimed. The bus got stuck in the mud and mussels, Pierre said. So he’d lashed an old hawser, with a buoy on the end, around the VW, and called it good.

At high tide, Pierre returned in his brother-in-law’s boat and grabbed the floating buoy. He took in the slack and hitched the thick rope to the stern. Then he put the boat in gear and towed the submerged bus across the harbor bottom, dragged it around the Indian Ledge and out to the deeper backside of the breakwater.

Without ceremony, Pierre slashed the rope, freeing the VW, which sank and joined the dozens, if not hundreds, of dead cars and trucks buried in the watery junkyard. The vehicles created an artificial reef shunned by the lobstermen, but not because of the batteries and oil left behind. They didn’t want their traps to get snagged on mufflers, or stuck in a trunk, or hung up on a smashed windshield. The lobsters loved the junkyard during the warmer months, spending their time darting in and out of vehicles, taking naps on deteriorating bench seats and finding secret hideaways in glove boxes and wheel wells.

Donald wasn’t pissed about the way Pierre was getting rid of the VW. He was just outraged that Pierre had the audacity of leaving the van in front of his wharf. Donald didn’t give a damn about the environment. The ocean was his trash can. A couple times a week he brought a paper bag of trash out to haul, mostly glass and tin, and threw it overboard. He’d been throwing plastic of all sorts into the sea for years, but stopped after his grandkids harassed him about it. So he burned the plastic, along with paper and cardboard, in his 55-gallon burn barrel in the back yard. The smoke was thick and black and the smell lingered in the neighborhood long after the fire was out.

But it’s pretty damn tough to get rid of a large household appliance via boat or burn barrel. Mary-Margaret bought a new washing machine, so Donald and I lugged the old one into the back of his pick-up and drove to the aptly named Steep Banks, the island’s tallest cliff. There, we pushed the washer off the back of the truck, to join a rusting white and avocado-green trail of appliances that reached the water’s edge and was visible a mile away.

Look Out!

Aside from the tryst with the cougar, there was no romance for me until the end of the summer, when I met Alice, a 32-year-old school teacher from southern Maine. Her grandparents had moved off Matinicus to find work, decades ago, but had kept the family homestead as a camp. A pal introduced us, and we hit it off immediately, enjoying a dinner at the island’s version of a restaurant: Someone’s illegal, backyard picnic-table café. After dinner, she took me home to her grandparents’ sparsely furnished house where we really got to know each other.

The next morning, Donald and I rendezvoused, as usual, 10 minutes before dawn.

“Where were you last night?” he asked. “Couldn’t find you nowhere. Coast Guard called about a sinking boat. Ended up having to go rescue them all by myself.”

Donald had an unusual relationship with the Coast Guard. Because the island was so far off shore, at the outermost edge of Penobscot Bay, Donald often helped the Coasties with search-and-rescues. No money was ever exchanged, but Donald was welcome to tie up at the Rockland station, where the Coasties would keep a watchful eye on his boat and occasionally fill his fuel tank.

So while Alice and I were rolling around on the kitchen floor, Donald was en route to an emergency. A 37-foot boat under full sail, rented and commanded by a rich landlubber from New Jersey, had crashed into Matinicus Rock. Apparently, the skipper never saw the 90-foot-tall lighthouse because he was below deck having sex with his mistress.

Jagged rocks tore a huge hole in the hull and the boat took on water wicked quick. After screaming MAYDAY into the radio, the couple escaped by climbing into a little boat they’d been towing, a rubber skiff with a three-horse outboard. They waited for rescue, bobbing in a gentle sea, as the sailboat went down. Every 10 seconds, the darkness was interrupted by a blast of light pulsing from the Rock’s towering beacon.

Donald reached the lovers minutes after the sailboat went under. He lashed the dingy to his stern and headed toward the mainland with the two grateful passengers aboard his lobster boat. The Coasties met him halfway and took the couple aboard their 41-footer, but wouldn’t take the skiff. Their job was saving lives, not personal property. Donald agreed to keep the little boat until arrangements to retrieve it could be made.

Donald was tired and grumpy. He didn’t get back to the mooring until half past midnight. And now, five hours later, it was time to work. We got underway and headed to the spot of the previous night’s drama, where 250 traps in shallow water needed hauling.

We arrived at the Rock as the sun cleared the horizon. In the early light, we could see the very top of the sunken vessel’s sail breaking the surface of the water, like a three-foot-tall toy boat. Waves splashed over the mast. Puffins landed and swam around the sail. I wished for a camera.

“That fella was clueless,” Donald said. “When I picked them up, he had no idea where he was. Thought he was almost to Bar Harbor. Friggin’ moron!” He sighed and shook his head. “They’ll rent a boat to any idiot with a credit card.”

We started to haul our traps. A half hour passed and I was stuffing bait bags with rotten herring when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw something leap from the water.

“Donald,” I said, pointing at the brightly colored object floating 50 feet off our starboard, “what the hell is that?”

He put the boat in gear, came about and around, and gaffed the thing with his hook: A basket of silk flowers! A few seconds later, whoosh, another object, large and brown, emerged from the depths with such momentum that, for a moment, a table actually broke free of the ocean’s grasp and went airborne. Then several upholstered cushions popped to the surface like corks.

“She’s breaking up!” Donald squealed gleefully. “Right now! We’ve got salvage rights!”

We fished the mahogany galley table out of the drink. The table had a storage box inlaid in the center and inside it I discovered treasure: A cup full of quarters, dimes and nickels. About 10 bucks’ worth of change!

“That table would be nice in the fishhouse, but the rest ain’t worth a damn,” Donald said, pointing at the floating debris. “Gonna keep the bouquet for Mary-Margaret. She’s always complaining about me never gettin’ her nuthin’!” He cackled and snorted. “Well, dear, I got you some flowers!”

Donald also kept the skiff. His grandkids had a blast scooting around the harbor in the little boat. The guy from New Jersey called, and so did somebody from the insurance company. Donald told them both the same thing: The Coasties must’ve taken it ashore; he didn’t know nuthin’ about no boat.

Danger Island

The salvaged table improved the décor of my pad. I paid 60 bucks to a handy fella on the mainland to build a new base for it out of pipe. My typewriter fit well on the table, next to a couple piles of books, papers, and a big ashtray. I made a special spot for a whiskey bottle and my small bong, and there was still enough room for a plate of potatoes or a bowl of pasta or a heap of mussels or a couple short lobsters.

I was a rich man. Making five or six hundred bucks a week, sometimes a hundred or two extra, thanks to Donald’s side-job bringing pilots to and from the huge tankers and freighters plying the waters off Rockland and Searsport. Finally able to afford creature comforts here-to-fore unknown to me, I got rid of the cot and bought a futon. And a pretty good stereo, a better pair of work boots, pots, pans, plates and tons of books, thanks to my membership in a couple different paperback-of-the-month clubs, plus Rockland’s awesome used bookstore, where I’d stock up during my monthly journey to the mainland.

After one of those trips, on the way back to Matinicus, Donald decided to visit a Russian fish-factory ship, called the Riga, at anchor in the harbor. I didn’t know much about the vessels other than they were buying megatons of pogies. Occasionally they would weigh anchor and head out to sea – to waters not far from Matinicus – to pump their holding tanks empty of the shit and piss of a hundred Russian sailors.

It was a Sunday and because you can’t lobster on Sundays during the summer, we had a little time to kill. We pulled alongside the Riga and Donald shut down the engine. Dozens of sailors lolled about the decks smoking, about 15 feet above us. We shouted hellos back and forth.

“Smokes?” one of the fellas asked. “Cigarettes?”

Donald smiled and shook his head no, but I went straight for my backpack. I had two cartons of Camel filters. I could buy more cigs on the island (from the bootlegger who charged twice the price) so I had plenty to trade with these Ruskies. I showed my smokes and the bargaining began via a wire basket they took turns lowering and raising.

Ten minutes later, I was the proud owner of three Russian merchant marine uniforms, a half dozen Russian news magazines and three packs of filter-less Russian smokes called Cowboy. The cig packs were made of yellow rice paper sporting the logo of a cowboy riding a bucking bronco.

In exchange, I gave them most of my Camels, plus the Coast Guard ball cap I wore as a joke to complement my increasingly long hair. They also received several periodicals, including issues of The New Yorker and (the hilariously ironic) Spy magazine.

It was only later, back on the island, after unpacking in my room, that I discovered some very important papers concerning my discharge from the Coast Guard were missing. I’d brought them ashore to make photocopies so I could apply for an able-bodied seaman’s license. For safekeeping, I had stashed the originals and the copies in the latest issue of The New Yorker, now in the hands of Russian sailors. Oops.

“Dudes!” Paul shouted. “The skiff!”

It was the end of September and the three of us were standing in the middle of Ten Pound Island. Drinking Lord Calvert, but not drunk. High, but not obliterated. Even though it was less than a mile from our shacks, none of us had been on Ten Pound before. I was enamored with the island because of a particularly memorable foggy day, early in the summer, while hauling traps between Matinicus and Ragged Ass. The salt air and mist smelled sweet and fruity because Ten Pound was overrun with wild strawberries.

So the fellas and I borrowed a skiff without asking and went for a joyride, landed on Ten Pound, then wandered the island, exploring the 20 acres. After we smoked a couple joints, we looked back toward Matinicus.

That’s when Paul remembered the skiff and we ran to the spot where we’d landed. We had neglected to haul the boat up very far, thinking we’d only be on Ten Pound for a couple minutes. Back on the shore, we saw our ride home bobbing in the rising tide.

“Fuck, fuck, fuck,” Paul yelped and sprinted toward the water’s edge and waded right in, not bothering to pull off his sneakers. He kept going, farther and farther until the frigid rising tide was almost to his chest. He pressed on until he had to start swimming. Keeping his head above water, he paddled toward the drifting boat.

If the skiff got away and left us stranded, we’d be in big trouble. Our captains would’ve been pissed when they couldn’t find their sternmen. Plus, the fella whose skiff we stole would’ve been livid when he discovered it missing from the Steamboat Wharf. After a while, a search would have to be launched and we’d all be wicked embarrassed, cold, starving (with a wicked case of the munchies) and thirsty (because of cotton mouth) when and if we were found.

“Go Paulie! Go Paulie!” Benny chanted, thrusting his fist in the air. “Go Paulie!”

Our hero caught the skiff and easily pulled himself aboard while we cheered. A minute later, he had the outboard going and ran the skiff aground to pick us up. We raced home, because he was freezing. A potential crisis averted. Paulie saved the day.

On the island, my reckless behavior went unpunished. When each day’s haul was done and the captains went home to yell at their wives or fall asleep in front of the TV, the harborfront came alive with the sound of rock’n’roll and the shore was owned by the sternmen. Silly bets and dares – usually involving feats of strength or copious consumption of booze or drugs – were commonplace. When and if the occasional single (or not single) woman appeared, we puffed our chests and preened like puffins. Praying, wishing, dreaming for a miracle, hoping we’d get laid.

The island bootlegger preferred to make only one delivery trip a night to the shore. So we usually placed a collective telephone order. A half hour later, she’d show up with our Lord Calvert and beer at triple the price she paid in tax-free New Hampshire. Sure, the booze was expensive, but she delivered promptly, let us run up a tab and was a super-sweet woman (with a gruff, but kind, husband) who was selling booze to help pay the bills. So we never complained because her surcharge was more than fair.

Other drugs came in other ways. My cache of psilocybin mushrooms came stashed in a VCR tape box via the U.S. mail. The smokables came from fishing boats from Vinalhaven and Rockland that would visit weekly for an hour or two. Occasionally, one of the seedier Matinicus boats would meet up with another vessel in the spot of open ocean halfway between the island and the mainland. The ganja was often Maine-grown, but the hashish was sliced from a brick stamped in gold, allegedly from Lebanon, and weighed like you were at the deli.

We didn’t party every night and most times, I’d be home by eight p.m. at the latest, ‘cuz everyone had to haul the next morning. We’d play spades or pitch, sometimes rummy. We held ping pong tournaments at Benny and Paul’s shack. We’d occasionally make huge collective meals, with short lobsters, spaghetti, or hot dogs and hamburgers on the grill.

Life was pretty simple. Working for Donald made me stronger than I’d ever been in my life. And I was a very good sternman, because the job was simple after you set up a system and stuck with it. And best of all, the gig left me with enough time to focus on my art. Most evenings, I smoked pot, drank Lord Calvert and labored on poorly-written narrative poetry about the mess in Haiti, which I blamed on widespread corruption and U.S. support for dictators.

For a six-month stretch, I fancied myself both a poet and a struggling painter. My experiments tended to consist of tiny pieces, fiery splotches of orange, pink and purple on blue, captioned with words and letters cut from magazines and newspaper. I briefly incorporated shaving cream, soap, shampoo and toothpaste into the mottled medium, with less than remarkable results.

For entertainment, I read a lot and listened to public radio and WERU, a community station in Blue Hill. And smoked a bunch of herb, looked out the window and thought about life.

The biggest drawback was Donald. Even on days we didn’t go out to haul, he hung around the shop to avoid spending time at home. He came down at the crack of dawn and used the table saw to cut oak runners for new traps we didn’t need. Or he’d fire up the compressor to run air tools. Both were located five feet from my futon, through a thin wall. The racket made it impossible to sleep.

So on days off, I’d take a couple peanut butter sandwiches, a thermos of tea, some reefer and my notebook, and escape. I’d walk to Markey’s Beach or South Sandy, climb to the top of Mount Ararat, the island’s lone hill, or poke around the Ice Pond. Often I’d disappear into the stands of spruce and pine near the airport. I discovered a giant boulder on the west side of the island, warm by noontime, that radiated heat into the night. An amazing spot for a nap.

Just as often, though, I’d hang out in someone’s fishhouse and get high.

“Crash, go move the truck,” Donald said, with a hint of a slur in his voice. By October, Donald barely spoke to me, other than to give a direct order. “Just don’t crash it. Hah-hah.” He tossed me the keys.

Mary-Margaret was giving us both the evil eye. We were attending a birthday bash in Lincolnville, a little town just north of Rockland, for an old-time sea captain and maritime pilot. We were already on the mainland for our monthly trip, so Donald and Mary-Margaret decided we’d make a surprise appearance at the party for Cap’n Craiger. The gala was being held at a camp in the woods and there were lots of vehicles. Parking was a chaotic mess, though Donald was able to maneuver his giant Chevy truck among the trees and parked cars.

The plan was to be there for a minute or two, enough time for us to pay our respects, then get on down to the boat and back out to the island. But then Cap’n Craiger got ahold of Donald and wouldn’t let him go. They were old pals, a half-century at least, and Donald owed a lot to Cap’n Craiger for setting him up in the lucrative business of being a pilot tender.

All the massive tankers and freighters that made port calls at Rockland and Searsport flew foreign flags, so they were required to bring a local captain aboard who was knowledgeable about the tides, currents and submerged obstacles of Penobscot Bay. Since Matinicus was the closest to the buoy marking the outermost reach of Penobscot Bay, the pilot company put Donald on permanent retainer decades before to serve as their offshore taxi driver and innkeeper.

So when Cap’n Craiger offered Donald a nice drink of scotch, there was no way he could turn him down. And once that booze hit his tongue, Donald was a jovial man. The first sip changed his entire demeanor. He glowed. Transformed. A back-slapping joke-teller, almost, Down East style. He laughed. He smiled. His eyes sparkled. But I knew the truth: The glint was merely the sunlight reflecting off the inside of his vacant skull. He was a racist, sexist, homophobic, polluting curmudgeon. Under the glow of alcohol, however, he seemed almost tolerable. With a drink in his hand, telling stories and spinning yarns, Donald was the life of the party.

Another guest needed to leave, but Donald’s giant truck was in the way. So he tossed me the keys even though he knew I was a terrible driver. I ignored Mary-Margaret’s glare as I climbed into the truck and started it up.

The pick-up was wedged in at a strange angle among several other vehicles. I put her in reverse, turned the wheel and backed out. Or tried to back out. I was riding the clutch and a little nervous trying to maneuver in front of an audience. Finally, I let up enough on the clutch and the truck lunged and lurched backwards and out, but not before nicking the edge of the beat-up station wagon next to us. No damage to the other vehicle, but Donald’s quarter panel was dented and scratched.

Of course this truck was his pride and joy. For flashy fishermen like Donald, island vehicles were beaters, but mainland trucks were status symbols. And this was a year-old Chevy behemoth, with an extended cab and bed, sporting a polished truck cap with shiny chrome accents.

“YOU STUPID SON-OF-A-BITCH,” Donald yelled as he opened the door and pulled me down and out of the truck. “CAN’T YOU DO ANYTHING FRIGGIN’ RIGHT?”

It was official. We hated each other. I stood there, shaking, enraged and embarrassed. Nobody calls me a stupid son-of-a-bitch. It took all my willpower not to slug him. Sure, he was a tough old coot, with giant arms and hands, but I was tougher. Stronger. Younger. Angrier. I could kick his ass. No fucking problem.

But where would that leave me? In jail. Jobless. Homeless. Broke. And what would it prove?

The simple truth was this: Donald thought he hired a crew cut, but got a long-haired hippie instead. A dependable and efficient hippie, but a hippie nonetheless. Problem was, he couldn’t afford to get rid of me because the fall fishing was good and he didn’t have time to find and train a new sternman. He’d keep me, I was sure, at least until March, when he headed to Florida for a month.

He fumed during the drive back to the boat, the long trip out to the island, and for the next couple of days afterwards.

Then one night the following week, over a soggy chicken dinner with fake mashed potatoes and canned gravy, Mary-Margaret made the big announcement. The truck was fixed.

“I’m going to be deducting $400 from your pay for the repairs,” she said, smugly. “It’s only fair, since it was your fault. Do you want to split it over the next couple of paychecks? I can do that, if you want?”

She looked at me expectantly. Almost daring me to challenge her.

I didn’t say a word. Nothing I could do. They had me by the proverbial balls. I was their slave and they paid me what and when they wanted. And if I bitched, I knew they’d snort and tell me to leave.

“Well?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said, sinking into the realization that I was powerless. “Do that.”

“Plus you owe me a hundred dollars for your sweater wool.”

“Oh,” I said. When she’d offered to knit me a sweater, I didn’t know she was gonna charge me for it.

“You can pay for the wool,” she said, “after the truck repair is paid off.”

I didn’t say a word.

“My hand is killing me,” I told Donald on Halloween. “Something is wrong with my middle finger.”

“My hand is killing me,” I told Donald on Halloween. “Something is wrong with my middle finger.”

“Well, you better tough it out, ‘cuz we can’t stop now,” he replied. “Not with this weather coming.”

We had less than 24 hours’ warning before the awful weather that would be immortalized in Sebastian Junger’s book, The Perfect Storm. All the islanders were in a twitter because Matinicus still bore scars from the winter storm that wreaked havoc in 1978.

So we worked long and hard, shifting most of our gear to deeper water to keep it from getting stove up on the shore. And when we re-set the gear, Donald was careful to put some real distance between us and other strings of traps, to prevent his gear from becoming part of a giant trap ball – an underwater rolling tumbleweed of lobster traps – created by violent sea surges and wave action.

Our final task was to take up forty traps and put ‘em on the wharf, which, for me, meant a whole bunch of coiling of rope and stacking of gear and buoys. All while my finger throbbed and pulsed.

After we put The Dotted Eye back on the mooring and made the bridle extra secure, we headed ashore and joined the rest of the crowd down at the store beach. Friends and mortal enemies alike worked together hauling skiffs and dories far above the high water mark. Camaraderie and joking set the mood. By sunset, everyone headed home for dinner, but most of the islanders were gonna come back, at high tide, when the storm’s wrath would be the worst.

Meanwhile, my finger was swelling something wicked. And it throbbed, like I’d whacked it with a sledge hammer. Mary-Margaret was no help and there was no nurse or doctor on the island. With a major storm headed our way, all the boats were on their moorings and gonna stay there. The Coasties couldn’t be bothered for a sore finger. So a friend hooked me up with a handful of opiates in pill form to quell the pain.

I sat at my table, in the dark, smoking cigs and listening to the wind and rain howl and scream as the building shook. Through my window, I could see the boats straining at their moorings and waves crashing over the breakwater. The wharf moaned, quivered and groaned as the harbor churned and swirled. Pondering the situation through an opioid haze, I wondered about my safety. Could the old shack handle the storm? Would I end up buried in a collapsed pile of lumber? I wanted to go stand on the wharf, at least for a little bit, to experience the weather. But I couldn’t move. Not a chance. Not scared. Immobilized. Stoned out of my gourd. Thankfully, feeling no pain. Eventually, despite the storm raging outside, I fell asleep.

The next morning was bright and cheerful. The air was clean and brisk. There were still some waves, but nothing extraordinary. The island fared well. Other than some leaky roofs and flooded cellar-holes, Matinicus survived the storm unscathed.

All the fingers on my right hand, however, were swollen. And red lines and streaks appeared on my wrist, reaching for my forearm. I arranged for an emergency ride in the mail plane to the mainland, then took a taxi to Pen Bay Medical Center. Blood poisoning, they said, from a sliver of fishbone jammed deep into my middle finger just below the nail. I would have died, they said, if I hadn’t come ashore.

I was given a regimen of antibiotics and told not to drink booze for two weeks. Another cab ride brought me to downtown Rockland, where I enjoyed a nice Mexican lunch at El Tico Taco, before cabbing it back to the airport to hitch a flight out to Matinicus. I was gone for eight hours.

So much for remote.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, my beloved grandmother was dying. The Tuesday before Thanksgiving, I headed to Massachusetts to visit her. She passed the next day. Coincidently, it was also the week of my fifth year high school reunion and my parents urged me to attend. Long-hair and a beard full of herring bones was my look. Former classmates, most of ‘em college graduates, were tidy and neat in the first year of their careers. Uncomfortable and feeling clumsy, I got wicked drunk and high. And sad. Very sad.

Nana’s wake and funeral were in Boston. I hadn’t seen her much in the last couple of years because of my globe-trotting Coastie lifestyle, followed by Matinicus, but she was the first person I ever truly loved who died. I had no idea grief was so strong, able to suddenly cut so deep. I had trouble keeping my shit together. Being in a noisy city, and among a family that viewed me as a dark, black sheep, made me more heartbroken and tearful. And so-called civilization seemed so foreign. Hard, loud and busy. I longed for the solitude of my little room on the island.

After the funeral, my immediate family gathered for an impromptu portrait since we hadn’t all been together in a long time. We stood on the steps of a Boston Catholic church. I wore a brown, double-breasted vintage sports coat I picked up at Goodwill. I stood in the center amongst my three sisters, two brothers and my mom and dad. Inexplicably stroking my chin, sporting a full beard with my curly hair reaching for my shoulders, I looked like a werewolf.

The World’s Largest Christmas Tree

The phone rang just after I snorted the third long line of cocaine. It was Captain Donald calling. We were supposed to have the night off, but an unforeseen ship was heading out to sea, and it was our job to pick up Cap’n Craiger, who was piloting the visiting vessel.

My job as “lee captain” was to stand on the bow of The Dotted Eye as we pulled alongside ships. I held the bottom of the ladder steady while we picked up or dropped off the pilot. When the transfer was complete, we’d turn around and head home. For this, I earned 50 bucks. Great pay for less than an hour’s work.

We usually had a day’s notice, but on this foggy and moonless mid-December night, it was a matter of minutes. Donald had telephoned earlier to let me know a freighter was headed our way, but I missed the call because I was at my buddy’s fishhouse buying an eight ball of coke. If I’d known a ship was enroute, I would’ve skipped the blow and settled for a mellow puff of reefer and a nip or two of cheap Canadian whiskey. Instead, I was soaring. The cocaine was fine and the lines I’d razor-bladed in my shack on my mahogany table were gigantic.

Donald wasn’t sober either. He’d already enjoyed his monthly tall glass of Scotch when he was notified of the surprise ship. I could hear the slur in his voice.

Aboard The Dotted Eye, both of us aglow, we headed for the rendezvous. It was windy, but warm for December. A low-lying winter fog engulfed us. Looking straight up through the shadowy mist, I saw a million stars. Engorged with cocaine, my brain absorbed the beauty, then turned paranoid. What if we had an accident? The Coasties would conduct tests and discover Donald was drunk and I was coked to the gills.

The 600-foot-long ship was hidden by the night vapor, invisible but for a large green blip on Donald’s radar screen. As we got closer, Donald motioned for me to take my place on the bow. The sea had a slight chop, maybe two or three footers. Nothing I hadn’t handled a thousand times before, but enshrouded in fog, and worried by cocaine, the ocean loomed unpredictable and dangerous.

The sky above the fog banks suddenly caught fire. Giant balls of light flared like those old camera flashcubes and blinded me, destroying my night vision. The ship’s crew seemed to have energized every lantern, lamp, klieg and searchlight – from the main deck to the bridge, up the mast and into the glowing crow’s nest – a triangle of luminosity that transformed the vessel into the world’s largest Christmas tree

The sky above the fog banks suddenly caught fire. Giant balls of light flared like those old camera flashcubes and blinded me, destroying my night vision. The ship’s crew seemed to have energized every lantern, lamp, klieg and searchlight – from the main deck to the bridge, up the mast and into the glowing crow’s nest – a triangle of luminosity that transformed the vessel into the world’s largest Christmas tree

Instinctively, I raised my right hand to shield my eyes and, in doing so, let go of the safety rope just as the sea surged, pushing the lobster boat hard, rolling her heavily to port. My body pitched toward the churning waters between us and the ship.

Everything went into slow motion. Was this the way I was gonna die? A hundred feet astern of The Dotted Eye, a pair of larger-than-man-sized propellers were turning, spinning, ready to slice, dice or drown me. An instant later, the lobster boat rolled back. I regained my footing. My right hand grabbed the safety line and didn’t let go.

Cap’n Craiger, a salty, sprightly 75-year-old elf of a man, clamored down the 50-foot rope ladder hanging from the ship’s lowest gunwale. He skipped the last five rungs and jumped, dropping himself onto The Dotted Eye, landing with a thump. Safe and sound. Donald turned us about, headed for home.

Vance Bunker, Hero

In the summer of 2009, Matinicus made national headlines after one lobsterman shot another in the neck during a trap war. The shooter, Vance Bunker, was ultimately found not guilty. Rightly so, because Vance, frustrated by harassment and threats from longtime enemies of his family, merely defended himself against a couple of scumbuckets. And the shooting wasn’t the first time he acted like a hero.

From my perspective as a sternman, Vance Bunker was an awesome guy. A gentle, funny giant. An island Renaissance Man. He was old enough to remember hauling spruce traps, but young and intelligent enough to embrace modern improvements. Smart about the ocean, he drove a boat like it was an extension of his body. And he could fly. On several occasions he gave me a lift to the mainland in his tiny plane. He was kind and generous, tough and strong – his hands as big as heads, his arms mighty muscles developed during a lifetime of hard labor, working the waters off Maine’s most remote island.

January 16, 1992 was a frigid night. The outer reaches of Penobscot Bay swirled. The sea smoke was thicker than fog. Screeching winds gusted over 30 knots. Four-to-eight footers of North Atlantic chop. That’s the weather the tugboat Harkness was trudging through when she started taking on water. Lots of water. The crew believed they were doomed. The sea was so rough, no fishermen would be out. They were too far from shore for the Coasties to help. They gave their position, via Loran numbers, over the radio. MAYDAY! MAYDAY! They were going down.

A voice on the radio urged them to head for Matinicus. The crew had seen the island on the chart and assumed it was uninhabited. Not so, the radio voice said. “Steam for Matinicus, it’s your only chance.”

On the island, people sprung to action. Vance, along with Captain Rick Kohls and island handyman Paul Murray, climbed aboard Vance’s lobster boat, the Jan-Ellen, and headed toward the tug’s last known position. The plan: Lead the Harkness safely into the harbor and lean her against the Steamboat Wharf. The rest of us would bring the dewatering pumps on the fire engine.

The fire truck wouldn’t start, but it didn’t matter. No pumps could beat that winter night’s watery wrath. Out at sea, the tug’s stern went awash. The three-man crew abandoned ship as she went down, deep into the North Atlantic. Gone forever.

Meanwhile, Vance and his crew battled the freezing spray and waves. The Jan-Ellen was icing up. Couldn’t see through the windshield. Nothing on radar anywhere near the last known position. They wouldn’t spot the tug, since Davy Jones had already taken her. These three island men, however, were hardy and determined. Engulfed in sea smoke, there was no sky. They stared into the churning gray-and-black froth all around them. Searching. Seeking.

The men in the water? Bobbing. Bone-chilling waves broke and tossed them. Were they praying? Crying? Each man knew his end was near, in minutes or even less. Did panic set in? Or sorrow? Hypothermia follows. Drifting. Drifting toward unconsciousness. Cold. So very cold. They must have known death would soon arrive.

But a miracle happened. One of the tug’s crew had grabbed a waterproof flashlight (a Christmas present from his daughter) before abandoning ship. His right hand was seized up and clenched tight around the gift. His frozen claw glowed into the dark night.

The men aboard the Jan-Ellen saw the light. In the middle of the savage sea, they pulled the sailor aboard. And then, wondrously, they spotted and snatched the two other men from the Reaper’s grip.

Vance turned toward the island. His crew tore the wet clothing from the survivors and gave them semi-dry gloves, hats, and the coats off their own backs. When the Jan-Ellen arrived at the Steamboat Wharf, the Matinicus men stood in t-shirts and trousers, half-frozen. But not as cold as the crew of the Harkness.

I know, firsthand, how cold the rescued men were. As one of three sternmen standing on the wharf, I was chosen as a warm body and found myself in the back of someone’s truck, sharing a sleeping bag with a fella just plucked from the sea. Stripped of his soaked loaner coat and hat, his bare body was ice. I wrapped my arms around him and snuggled the shivering, chattering, nearly naked man. I remember his tighty-whities, wet against my pants. I shared my heat, across the island, until we got him inside Vance and Sari’s house, where there was a warm fire and a huge pot of lobster stew. And biscuits.