Home and Cocktails

categories: Cocktail Hour

10 comments

We have lived in our new house for about a month and half. I have never owned a house before, but I spent my whole adult life dreaming of having a place to call home. It is strange that that house turns out to be in North Carolina, but less strange that it turns out to be on a salt marsh. Not only is the marsh a miraculous ecosystem where I can now daily hear the strange applause of clapper rails, but it connects me by water to the many other coastal places I have come to love over the years. I don’t mean this mystically, but practically. If one day I am feeling particularly ambitious, I can hop in my kayak and paddle down Hewlett’s Creek out to the Intracoastal Waterway and to the Atlantic beyond, and then, after banging a left, can paddle north back to New England until I reach the Kennebec River. There I can take another left, and another on the Sandy River and then a final left on Temple Stream, which I can follow until I hit Bill’s house up on the right.

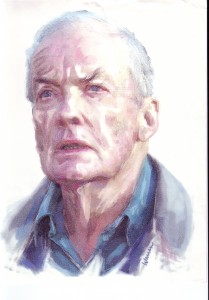

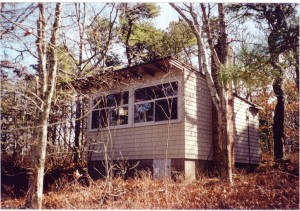

Of course the place where my creek most consistently pulls me back to is Cape Cod. There’s a fun little irony here, since Hewlett’s Creek is also “Dawson’s Creek,” and it is where the fictional Dawson’s house was filmed, and of course that fictional house was supposed to be on Cape Cod. But with apologies to the TV show, which I’m sure is a fine and worthy production, it is books and their writers which most connect my old home to my new. As we begin to settle in here, I think of the great nature writer, John Hay, who, somewhat to his own surprise, spent fifty years of so rooting down on Cape Cod. John had first come to Brewster in the early forties to offer his services as an apprentice to Conrad Aiken, the Pulitzer Prize winning poet. During his stay with Aiken, John had bought some nearby land, a “worthless woodlot” according to the locals, for twenty five dollars an acre. After serving in World War II, John felt as if the earth was spinning out of control. His response was to build a home on his woodlot and root down there, but at first he was unsure. He felt a bit like Robinson Crusoe, thrown up on a strange beach, and the landscape, hardly deep woods and majestic mountains, seemed scraggly and windswept. Eventually, however, he started to see possibilities in this place where he had not expected to stay. By the time I met him, and began to interview him for a book in the late 90s, he had become to many no less than a symbol of human rootedness. There was a sense of certainty and permanence to the man’s life, a sense that he had planted his flag in his one beloved place and that, no matter what happened in the uncertain world, he would be staying there forever. This is nice, and important, but just as important is that the house was built on a foundation of uncertainty.

Lately, as I move into my first home, I have been thinking a lot not just about John, but also about Conrad Aiken. Recently I dipped into Aiken’s Collected Letters and learned that Aiken and his wife, Mary, moved to Brewster in 1940. On May 21, 1940, the day the Aikens bought their house in Brewster, Conrad wrote to Malcolm Lowry:

“Ourselves, we pick off the woodticks, and pour another gin and french, and count out the last dollars as they pass, but are as determined as ever to shape things well while we can, and with love. Nevertheless, I still believe, axe in hand, I still believe. And we will build our house foursquare.”

The rest of the letters from Brewster are the sort of combination of pastoral and grumble common to those tackling renovating an old house in the country. Conrad spent his time “weeding the vegetable garden, mowing lawns, cutting down trees, shooting at woodchucks and squirrels, attacking poison ivy with a squirt gun,” as well as “scything the tall grass,” and, as usual, drinking copious amounts of alcohol. The poet, then fifty-one, had a good deal of pride in what he and Mary were accomplishing–“We both thrive on hard physical work, and feel extremely well”–and exalted in his new surroundings, surroundings that would soon work their way into his best poetry.

To shape things well while we can. That line from Aiken’s letter seems to me as good a credo as we start to make this place our own. I have also been thinking of something that another Cape cod writer, Bob Finch, once said to me about John Hay’s early years on Cape Cod: “That first flush of rootedness is unrepeatable.” It’s been years coming but at the moment I feel fully in that flush.

* * *

But lest I get too sappy, I should emphasize that there was another element that helped Conrad and John feel at home on the frontier-like Cape Cod of the 40s. That was booze.

“I had this sense that he and his wife might supply me with something I didn’t have,” John Hay told me once. One thing the Aikens supplied him with was liquor. Back then no living writer–not Bernard DeVoto with his evocation of the perfect martini or the liquor-soaked Hemingway or even Malcolm Lowry himself–could match Conrad Aiken when it came to the daily glorification of booze. “The ritual of cocktail hour represents the communion of all friendly minds separated in time and space,” wrote Aiken. His poetic elevation of cocktail hour grew so famous that even the napkins used for the Aiken’s pewter drinking goblets later found their way into an Updike novel. It was all very ritualized and elevated, and for the young John Hay the talk must have been only slightly less intoxicating: long, drunken monologues about poetry, art, “consciousness,” and dreams.

“My God, there was a lot of drinking going on in that house,” John told the Boston Globe in 1995. “The gin, the parties, famous writers dropping in. I never wanted to leave.”

If one of the roles of a mentor is to provide a different sort of parent, an alternate family, then Aiken fit the bill.

“He helped me because he took me out of my traditional background,” John said. “Which was so reserved.”

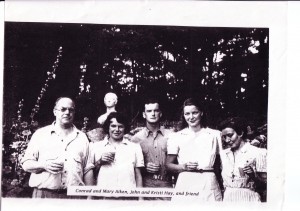

A photograph from the late ’40s, that I have posted above, captures some of that time’s magic. The Aikens and Hays stand close together in front of a statue in the backyard of 41 Doors. They hold the always-present drinks in front of them. Conrad appears slightly rumpled and perturbed, like someone’s angry Dad, while Mary, his much younger wife, smiles with obvious spirit–“She was the one who held it all together,” John told me–and the young Hays look like movie stars. Kristi in shoulder pads evokes Lauren Bacall, while John–young, dark and handsome–stares square-jawed at the camera.

I once asked John how he came to know Conrad.

“I sought him out really,” he said. “They had a lovely house in England, down a cobblestone street in Rye, where Henry James and Joseph Conrad had lived. I visited them after I graduated from Harvard in ’38 because a friend of mine had been in class with him at their little private summer school where Mary taught art, and where Conrad taught writing. I stayed with Aiken for a few days, marvelling at the whole scene. I had this sense that he and his wife might supply me with something I didn’t have.”

John explained that before he was drafted, he visited Aiken again at his house on Cape Cod. He stayed with the Aikens for a while, doing both yard and literary work, hoping to absorb whatever it was that made Aiken a writer. He talked to Conrad to “see if I couldn’t get in a little apprentice writing with him when the war ended.”

“It was Aiken’s personality as much as his work, that seemed almost immediately liberating, even thrilling to me. My parents, my mother in particular, believed in being proper and restrained, and that was how I was raised. Conrad was entirely different. Wild and uninhibited. Daring. I was drawn to him.”

* * *

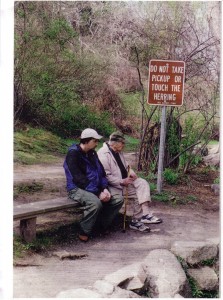

One day I drove John, by then almost ninety, down to the salt marsh where Paine’s Creek emptied into Cape Cod Bay.

“I drove Conrad Aiken down here when he was sick,” he told me.

I sat on a rock and John lay down in the warm sand, propping himself up on his elbow so he could look out at the water with his binoculars.

“We would drink orange juice and gin–he called them orange blossoms. When we came down from Boston we would stop at the Howard Johnson parking lot for our first drink. And then we would pull in here for a drink to celebrate having arrived.”

“His house spilled over with a wildness its walls couldn’t contain.”

He shook his head.

“People were much freer in those days,” he said. “In their conversation. In their insults of each other. Every way. They weren’t so sensitive about everything. So tightened up the way people are these days.”

I asked John if Conrad had helped loosen him up.

“Well, of course. You see he was a poet, and the way he acted was like a poet. I had never encountered a creature like him. You know my family was very proper, very New England, and they were always scared of such things. They thought you shouldn’t express yourself too loudly and you shouldn’t mention anything to do with your emotions because somehow the roof would fall in.

“Conrad wasn’t like that of course. Deep down he was very shy–and so he acted truculent and obnoxious at times because he was shy. But he was very generous to young writers like me. He was also friends with the writer Malcolm Lowry, and they got drunk as skunks together. It was all a very dizzying experience. It was dizzying being with Aiken anyway. First of all he had a constant obsession with the idea of ‘consciousness.’ I never quite understood what he meant by it to begin with, but he was always probing into this greater ‘consciousness.’ Even when he got drunk at night.”

John laughed out loud.

“At the end of one drunken night I said: ‘I suppose what you’re trying to do is forget everything and join the eternal dream.’ And Conrad said ‘That’s quite right.'”

* * *

A quick footnote to this piece. Students in my creative nonfiction class will rightly ask, “What’s the deal with all the dialogue?” And: “Did you ‘recreate’ it?”

Nope. The answer is simpler than that. Like Nixon before me, I have a love of the tape recorder. During the late nineties and early 2000s, I recorded many of my encounters with John. I was less sneaky than Tricky Dick and simply asked John if it was okay. At first we might have had a minute or two of self-consciousness, but soon enough we carried on as if the recorder wasn’t there.

Some of the scenes above have been recycled from the book that grew out of my encounters with John, The Prophet of Dry Hill. I thought it was worth reviving them to aid my current purpose and situation.

I live in Aiken’s house, Dave. It’s still appreciates good parties and your photo of the Aikens and the Hays hangs in the old kitchen! Please come by next time you are in town and we can share a martini!

Well, we are here right now…until tomorrow. Would love to peek inside the house!

I was at work til just an hour or so ago. The house is a terrible mess, right now. But call me at 385-3050 and we can all share a glass of wine! If not this time, definitely next time!

I don’t know if you have heard, but John Hay’s house is on the market…..

Liz,

See today’s post at Bill and Dave’s! Best, Dave

I have your book on my bookshelf and will now read it. Thank you Dave!

Cape Cod imprints itself deeply on young minds.

I’ve been gone from Massachusetts eight years, and I still feel the pull within me every autumn. Something within me is triggered. My body is looking for a change in the weather that isn’t forthcoming. If my decisions weren’t circumvented by such trivial manifestations of civilization as employment and home ownership, I’d probably head back.

Wouldn’t that be great? Giving in to the same elegant mechanism that’s governed animal migrations since the dawn of time. Handing myself over to the wildness within. Heading back to the beach where I was born without ever questioning the urge.

I’m not certain were capable of changing the place where we belong.

Dave I really liked this essay . It came from your heart. You are lucky you express your feelings so well. I recognized you in first photo but who are the others. George.

Beautiful piece…thanks

Our Brewster place is right near the Herring Run, thanks for psting the pictures. Reading John Hay’s books are a ritual for me and reconnect me to the Cape when I am unable to be there.

Much joy,love and laughter in your new home ( far from Flagg St, and Worcester)