Guest contributor: Rosie Bates

Getting Outside Saturday: Why I Climb

categories: Cocktail Hour / Getting Outside

1 comment

I started dancing at age 4, first ballet, then tap and ballet, then just tap, then tap and climbing, and then just climbing. I know I stopped being a dancer and became a climber when I was 14. But I don’t know when I started feeling like a climber—that could’ve been earlier. My dad taught me how to climb (starting when I was seven) and his dad taught him how to navigate the mountains and in turn my grandfather’s dad taught him how to enjoy the outdoors, I suppose. My dad finds solace in the mountains along with his dad, hiking through the snow, ice and sometimes rock of the North Cascades in Washington. For me, well, I find solace there too, but prefer to be high up on the vertical spires of granite, sandstone, and limestone protruding from the spine of Mother Earth herself. We could be called the evolution of the vertical life, moving forever upward in our quest for freedom in nature. But this process hasn’t been generational in the sense that climbing on its own has been passed down to me over the years. Rather the need for adventure has been passed on to me, the unadulterated respect for the environment and the continued quest for freedom.

So maybe I could say that climbing has been embedded in my bones since I touched down on this earth, but that would be a lie—something I could probably convince myself by telling enough people and soon it would become a part of my story. But climbing is different than that—get up on that rock face and everything is exposed, including the stories you have told over and over again just to convince yourself that you didn’t make it all up. You can’t hide anything when you climb, and if you do…well you aren’t climbing.

I remember climbing trips better than I remember my high school graduation, or the soccer games I won. I remember climbing trips, at least parts of them like the back of my hand. Whether I like it or not, these parts have been seared in my memory as small reminders of some of the biggest mistakes I have made or the best sunsets I have witnessed. For instance there was Zak. Zak, besides my dad, was my first climbing partner and arguably my worst. Zak is that rich person you desperately want to hate. You know, the most arrogant, pieces of shit, rotten, good for nothing—but you can’t. You can’t hate them because they have money, and you are only 16, not graduated, living under your parents rules. They entice you with the opportunity to travel places with their money, leave your parents for a weekend, and all you have to do is like them for that period of time. Zak knew just how to get me, and man did he have money—and by money I mean climbing gear, and all the climbing gear I could ever want. Zak was my gateway drug to the land of modern traditional climbers, the baddest of the baddest, the gnarliest motherfuckers you have ever seen. Trad climbers are the real deal and I wanted to be one of them. Sure my dad had introduced me to the sport, but honestly at 16 who would you rather climb with, your dad, or this cool older kid who had just finished his first year at college on the East coast? I chose Zak, and in a very short time it became clear to me I should’ve chosen my dad.

all you have to do is like them for that period of time. Zak knew just how to get me, and man did he have money—and by money I mean climbing gear, and all the climbing gear I could ever want. Zak was my gateway drug to the land of modern traditional climbers, the baddest of the baddest, the gnarliest motherfuckers you have ever seen. Trad climbers are the real deal and I wanted to be one of them. Sure my dad had introduced me to the sport, but honestly at 16 who would you rather climb with, your dad, or this cool older kid who had just finished his first year at college on the East coast? I chose Zak, and in a very short time it became clear to me I should’ve chosen my dad.

The drive to Leavenworth from Snohomish has always been one of my favorites. I sat squished in the back of Zak’s dad’s Toyota Tacoma, my parents had only let me go if his dad chaperoned us. I squinted out the tinted window into the backlit Cascade peaks, as we winded up through Steven’s Pass. Zak’s father noted this and handed me a pair of Oakley’s, “You didn’t bring sunglasses?” he asked in a baffled tone, “I don’t own a pair…” He stared at me, and said “you’ll need these then”. I took the “fire” series shades and watched as the mountains shifted from shadows to “electrifying sparks of oranges and yellows!” Oakley, I thought, how cool.

The drive to Leavenworth from Snohomish has always been one of my favorites. I sat squished in the back of Zak’s dad’s Toyota Tacoma, my parents had only let me go if his dad chaperoned us. I squinted out the tinted window into the backlit Cascade peaks, as we winded up through Steven’s Pass. Zak’s father noted this and handed me a pair of Oakley’s, “You didn’t bring sunglasses?” he asked in a baffled tone, “I don’t own a pair…” He stared at me, and said “you’ll need these then”. I took the “fire” series shades and watched as the mountains shifted from shadows to “electrifying sparks of oranges and yellows!” Oakley, I thought, how cool.

Highway 2 spans from Everett, WA to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan the furthest I have been on this road is Wenatchee, which is east of Leavenworth and about 2 hours from my childhood home. The road travels through towns that get smaller and smaller as you get further into the foothills of the Cascades; Snohomish, Monroe, Sultan, Startup, Goldbar, Skykomish… until you reach Steven’s Pass, where in the winter you can watch the tiny black dots—skiers and snowboarders move down the snow covered mountain while you drive by. When I was in my teens Highway 2 became equipped with signs that read, “___ days since last accident”, usually the number of accidents is only in the single digits. On this particular drive and it read 1. I always get a little weary reading this sign.

Highway 2 spans from Everett, WA to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan the furthest I have been on this road is Wenatchee, which is east of Leavenworth and about 2 hours from my childhood home. The road travels through towns that get smaller and smaller as you get further into the foothills of the Cascades; Snohomish, Monroe, Sultan, Startup, Goldbar, Skykomish… until you reach Steven’s Pass, where in the winter you can watch the tiny black dots—skiers and snowboarders move down the snow covered mountain while you drive by. When I was in my teens Highway 2 became equipped with signs that read, “___ days since last accident”, usually the number of accidents is only in the single digits. On this particular drive and it read 1. I always get a little weary reading this sign.

Zak and I barely spoke the whole car ride, except for the occasional exchange of climbs we wanted to do. We turned on to Icicle River Road, and the rocks began to emerge on either side of the car. Zak opened his window and the fresh mountain air filled the cab. I closed my eyes and imagined I wasn’t there with Zak, but with my dad or rather, alone. We parked in a pullout on the West side of the road as the sun was setting. Zak jumped out and I joined. His dad followed us like a paparazzi with his new camera strapped to a tri-pod and multiple lenses hanging off of his fanny pack. I chuckled at the idea of my dad’s snarky comment he would make in conjunction with this sight.

Zak and I barely spoke the whole car ride, except for the occasional exchange of climbs we wanted to do. We turned on to Icicle River Road, and the rocks began to emerge on either side of the car. Zak opened his window and the fresh mountain air filled the cab. I closed my eyes and imagined I wasn’t there with Zak, but with my dad or rather, alone. We parked in a pullout on the West side of the road as the sun was setting. Zak jumped out and I joined. His dad followed us like a paparazzi with his new camera strapped to a tri-pod and multiple lenses hanging off of his fanny pack. I chuckled at the idea of my dad’s snarky comment he would make in conjunction with this sight.

As we approached the climb I should’ve known that this first climb would be a sign of what was to come. I followed Zak up after he had climbed and set up a rope. I fell, he scoffed, I turned red and he just shook his head down at me. “Well this is going to be interesting” he remarked. What the hell could he mean by that I thought?

The next day we headed out to try something a little bigger. I lead the first portion of the climb—the first pitch. I was cruising. The small micro edges that I placed by rubber shoes on didn’t bother me. It was like clockwork, climb 20 feet, grab my quick draw, clip the bolt, clip my rope to the carabineer—breathe “ah, safe again”. I repeated this for the first five bolts, or the first 50ft. I moved over the granite placing my feet deliberately on the protruding crystals. I began to look around, noting the beauty of everything, the blueness of the sky, the greenness of the trees, the…”oh shit, where was my last bolt”. While I was getting all existential I had cruised right on past my last bolt and now stood 40 feet above my last piece of protection. In other words if I was to fall I would fall double that before my rope in the carabineer attached to the bolt would stop my body—and I calculated at 80 feet, that would put me on the ground.

Suddenly the rock didn’t look so perfect, and the leaves weren’t so beautiful. I saw the next bolt about 10 feet above me, and the last bolt I had missed about 10 feet below me. I couldn’t climb anymore and I sat paralyzed in fear, at the prospect I had messed up and now was destined to fall. Of course this is the mindset you never want to be in when you climb, and I couldn’t help but think that Zak had something to do with this as he sat on the other end of the rope. As I climbed I could feel his condescending tension pull at me—nagging me and telling me I wasn’t climbing fast enough.

He told me he broke up with his ex because she drank champagne on New Year’s Eve, I told him I had smoked pot once—he said he didn’t know if he could trust me; lucky for him he didn’t know I was lying—I mean come on, who smokes pot just once? I thought now, that maybe now all my pot smoking was catching up to me; man this guy was really under my skin. I looked around, and down and up back and…okay, come on now focus Rosie. I climbed down a few steps, no…I am already this high I may as well move upward and fall 100 feet. I moved up a few inches, to where I was just out of reach of the bolt. Damn it, all of this pot smoking has stunted my growth. I reached down and grabbed a sling with a carabineer on it as I gripped the rock with my left fingertips. I began to swing the sling wildly around as I aimed at the bolt. For some reason I was incapable of climbing at this point. I am sure with one more foot placement I could’ve been standing adjacent to the bolt where I could’ve like a normal climber reached out and comfortably clipped myself in. Rather I went for the irrational version of climbing where you stand in precarious positions swinging the rope around hoping a miracle happens and somehow you don’t fall.

After about 3 rotations, metal met metal and “shing! Safe!” I stood there for a moment thanking whomever for this blessing. It is funny, after clipping this bolt suddenly footholds appeared and the rock angled back down to just barely vertical, the trees regained their lush luster. I looked down at the not so far away ground and man was life good. Zak joined me, once I had finished my epic, up at the next belay station. He looked at me and said, “Well that was easy, and hey your little stint up there doesn’t change anything, you are still leading this next pitch—we are keeping to the plan”. I grabbed the gear from him, eager to be alone again and set out. I traversed out right, off the ledge I had comfortably been stationed on and looked down to about 250 feet of open space.

I looked back at Zak and he rolled his eyes. Fuck him, I am going to do this. I could see the next bolt about ten feet up from where I stood. I began to climb, and simultaneously began to shake. Zak huffed, “come on Rosie, keep it together”. I wanted to yell that point, “what do you mean keep it together!” Instead my foot started to shake more, as gravity seemed to exert a lot more force down upon my shoulders. I reached up to see if I could touch the bolt. I could, just barely. I reached back to my gear and grabbed a carabineer. As I moved my hand back up towards the shiny silver bolt I knew what was happening even before it happened. My Elvis leg couldn’t stand on the rock crystals any longer and my feet gave out. I began to fall even before I could let my life flash before my eyes. I fell down into that 250ft abyss, and watched the granite pass by me. There is always the moment when you are falling in which you think, “hmm, maybe today I won’t stop”. But just in that in an instant my rope pulled taught and I did stop, slamming against the wall below Zak. He looked down at me. “Shit Rosie, are you okay?” “Yeah, I’m fine”. “Okay good, get back up here, I’m taking this pitch because clearly you can’t.” A little shaken up by the fall, more by his demeanor I followed him obediently, and followed him the rest of the route. He didn’t talk to me till we began the descent down. His dad waited for us at the base with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Zak looked at me and said, “I thought you were stronger.”

As we sat by the campfire that night, looking at the guidebook with headlamps I felt pretty shitty. Zak was in high spirits as he told his dad of our day, a change from earlier. I reached across the table to grab some chips and sat back down, Zak reached down and put his hand on my leg. I froze, holy shit, I thought, this is how this trip is going to be. I looked up at him in disbelief and he just smiled. That fucking smirk I have learned to dread in any climbing partner’s face. The “I can climb stronger than you, so that means you are impressed by me, so hey, let’s get it on” smirk, the “hey baby, how bout we climb some rocks tonight” smirk. I turned away disgusted, and retreated to the safety of my tent—and got lost in the words of Steinbeck as I read “East of Eden.”

There you have Zak, and the vivid portion of that climbing trip I remember. After that trip I began to truly understand the difference between enjoying and enduring—and let me tell you the difference is quite clear.

There is a certain amount you must endure to get where you want in life, but when it starts to wear on you, and you lose sight of why you are even doing what you are doing well that is the worst feeling in the world. Zak was one of the few people I have endured climbs with, and it wasn’t because of the rock and maybe it wasn’t even because of him—but something about our experiences always left me with a bad taste in my mouth. Luckily I have endured few and enjoyed many more, which is why I have kept up with the sport—it is the standard benefits outweigh the cost argument. I climb because of the day my dad took me up my first traditional route and we sat at the summit eating crackers and cheese, for the days that I spent out at Tahquitz moving my way up through scattered pitons left by the pioneers in climbing and I climb for the days like the one that I finished Resolution Arete on Mt. Wilson in Red Rock, Nevada.

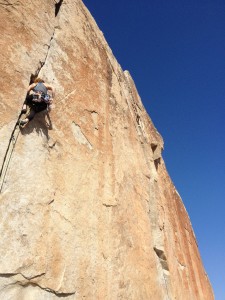

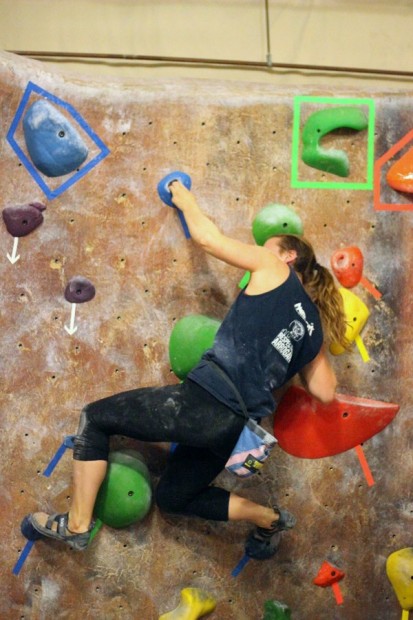

Resolution Arete travels up the right side of Mt. Wilson, which is the highest peak in the park. The route ends just 50 ft. short of the true summit of Mt. Wison, and has been climbed by only a handful because of the alpine like nature of the climbing—there is only one bolt on the entirety of the face, the rest is gear that we must place ourselves—making retreat nearly impossible. As I read and re-read the route description before the climb I kept getting caught up in the final statement by the authors that reads, “[on Resolution Arete] you will be very much alone”. As climbing has gained more and more popularity, areas with easy approaches and access are crowded with climbers of all ages and levels on the weekends—gym rats who come out to experience the “real deal”. I never minded this too much because I have always found ways to get away from it all. Resolution Arete provided me with that escape, but at a cost. The week before we left for Red Rocks the dreams had started–the blurred sepia-toned movie reel on repeat of me approaching the base of the climb and looking up at the ominous red speckled spire. I get nervous before climbs, and “being very much alone” while drawing me to this climb, scared the shit out of me.

Now I’m not one for trip-reports or detailed route descriptions; I’ve never been good with remembering route names or what gear to place along the way—things most climbers live for after a good climb. I tend to leave a climb humbled by it’s beauty and power—remembering not the moves and how they worked in sequence but how the rock reached out and grabbed me it’s red core pulsing through my veins as I bled up the wall’s wrinkled wisdom. Mike is the type of climber you go with when you want to get something done, and get it done fast. So we went after this route together. Trying to remember the details of the route now is a bit hazy. I remember the hike, and waking up at 2:45 to leave for the base. I remember watching the sunrise as Mike traversed out onto the sun-splotched sandstone. I remember falling on the 7th pitch, getting the rope stuck and losing a piece of my beloved gear. I remember scraping my hand as I attempted to get the rope un-stuck and sitting their bleeding imagining the prospect of having to somehow bail off the route. I remember placing my foot and shifting my body weight onto a knob that I knew was unstable and moments later having it break off as I screamed bloody hell and hung in the air searching to regain my composure. The route has turned into that sepia-blurred movie reel for me, pieces cut out and others meshed together as I search for the details. Yet in all of this searching I reach the last hour of the climb and suddenly there is pure-HD clarity, perhaps because it the most replayed part of the climb in my head.

Now I’m not one for trip-reports or detailed route descriptions; I’ve never been good with remembering route names or what gear to place along the way—things most climbers live for after a good climb. I tend to leave a climb humbled by it’s beauty and power—remembering not the moves and how they worked in sequence but how the rock reached out and grabbed me it’s red core pulsing through my veins as I bled up the wall’s wrinkled wisdom. Mike is the type of climber you go with when you want to get something done, and get it done fast. So we went after this route together. Trying to remember the details of the route now is a bit hazy. I remember the hike, and waking up at 2:45 to leave for the base. I remember watching the sunrise as Mike traversed out onto the sun-splotched sandstone. I remember falling on the 7th pitch, getting the rope stuck and losing a piece of my beloved gear. I remember scraping my hand as I attempted to get the rope un-stuck and sitting their bleeding imagining the prospect of having to somehow bail off the route. I remember placing my foot and shifting my body weight onto a knob that I knew was unstable and moments later having it break off as I screamed bloody hell and hung in the air searching to regain my composure. The route has turned into that sepia-blurred movie reel for me, pieces cut out and others meshed together as I search for the details. Yet in all of this searching I reach the last hour of the climb and suddenly there is pure-HD clarity, perhaps because it the most replayed part of the climb in my head.

About 500 feet short of the summit Mike and I stopped talking, except for the occasional exchange of commands. We moved forward slowly, tired, ready to get to the summit before the sunset and the rock was so loose—so rotten and aged. We knocked on every piece before we delicately placed our body weight onto the hollow flakes. We were focused and knew that mistakes now were not an option. Trudging up the last few hundred feet was a feat in itself but we reached the summit just as the sun was setting, I ran to the highest point I stood for a minute staring at the round geological survey marker, a sign that indeed someone else had also been up here. The bronze reflected the slowly fading light. Mike and I had just climbed almost 3000ft in about 10 hours. I looked up and scanned my hand over the desert; I could clearly make out the whole Vegas strip and placed the Luxor in between my pointer finger and thumb. It is at the top of climbs like these, right before the sun sets in which I feel free—all-powerful. I have seen the big walls in Red Rocks in many different forms and at different times. They both comfort and scare me. I always imagine them whispering knowingly “you don’t belong here; it is time for you to go home” as the sun sets and we begin our descents. But there is some sort of comfort in standing on top of them. For that instant all the fear of falling, having to hike down the unmarked trail in the dark, and my fatigued body giving out is forgotten. For the most part I am at a lost for words after climbing trips; I just want to feel the rock again, to feel the beating of the earth through it’s exposed appendages. There is something about leaving a climb—feeling a sigh of relief that I survived, but having the notion haunt me that I will be back soon to go through the process over again. I don’t know when or why I started climbing, or even what motivates me to keep on coming back. All I know is that I will be back because I am constantly searching for that freedom, even if it is just for a moment—I am an addict.

Video of Rosie and friend climbing at Yosemite: IMG_2629

[Rosie Bates was graduated recently from the University of San Diego, where she was on the climbing team. She’s a Mesa Rim Youth Team Coach and Route Setter. She has a really nice tattoo on her back. Her mother is Bill’s sister Carol Roorbach, which makes her an official Bill and Dave’s niece! Read her first Bill and Dave’s piece here]

Whew! I’m all tensed-up from the climbs! Great essay! 10 hours–my gosh! Love that Elvis leg.