Emma, by Jane Austen, Poolside, With Crocodiles

categories: Cocktail Hour / Reading Under the Influence

8 comments

In college I often was sad for my future self. For one thing, I was sure I wouldn’t have any fun on the millennial new year. I’d be 47 and dull and would have forgotten how to party, if still alive. But I was still alive back then in 2000, and still knew how to party. And still now, too, actually, even further into the Jetson era. Callow college fellows don’t know about the stamina of late middle age.

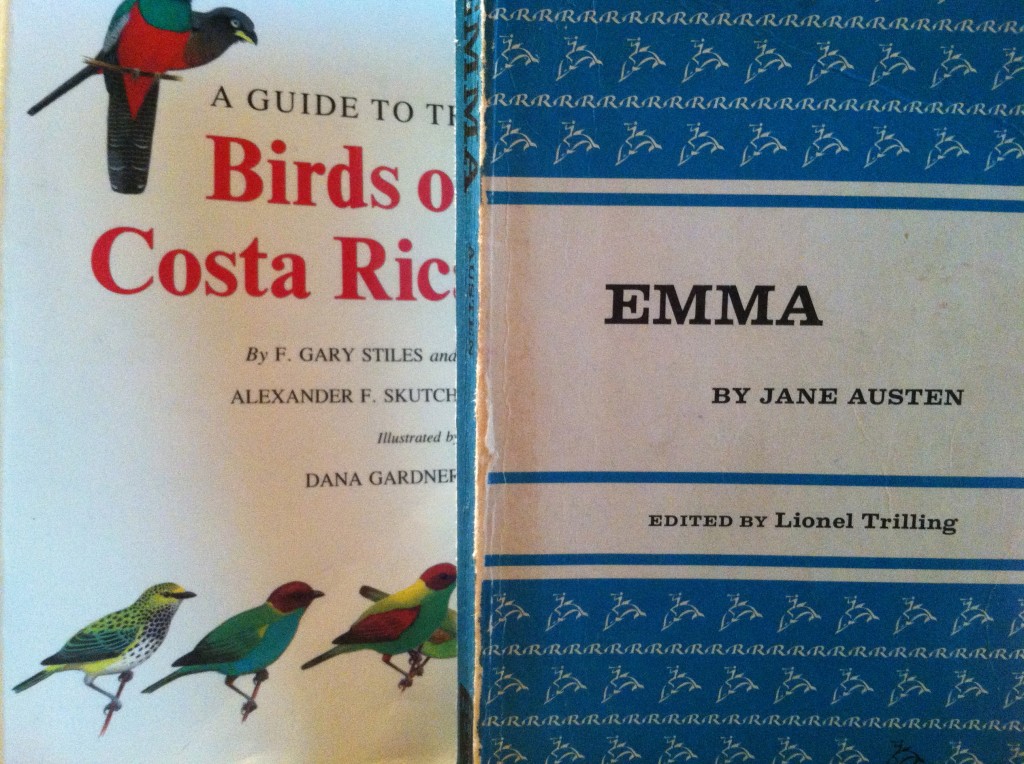

Another thing I was sad about was that I would have read all the great books by the time I was 30, and then what? So I embarked on a plan, one I kept up for many years. Greedily, I read all but one of the books of all the reputedly great authors, and saved that one for later decades. (I even saved Dickens entirely). Which is why Emma has been on my shelf wherever I’ve moved these last nearly forty years, unread. So last month, on the way out the door to Costa Rica, my daughter having nipped Great Expectations, I tossed Emma in my suitcase–something to read along with Birds of Costa Rica, which is more like the Bible (and to which I’ll return, in a post very soon). (I also brought along a library book: Tropical Rainforests, and it proved to be excellent. So more about that, as well.)

But Emma. It’s a later book of Miss Austen’s (as Lionel Trilling liked to call her), the last she saw fully into completion. And when in the second week of our adventure I finished Tropical Rainforests, and when I’d finished the days accounting of birds, I drew Emma out of the front pocket in my suitcase, brought it to the pool at our hotel in Manuel Antonio. And under an umbrella in the satisfying heat I began to read. First line, not so famous as that of Pride and Predjudice, but better: “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessing of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to vex her.”

Already I was happy I’d saved this one out. Clearly Emma, the character, was about to be vexed. And vexed, she turns out to be much more complicated than any earlier Austen heroine. The book is never as funny as, say, Pride and Predjudice. Emma is earnest, nearly. She’s a good person, but too insistent on that point, and very much too hard on others, nearly her downfall. She’s also a busybody. She lives with her father, and for his sake, plans never to marry. Which means, of course, that she must.

In order, betimes, to forestall frustration, she engages in matchmaking, and causes no end of trouble, which she comes to regret, offering apologies. It’s fun to watch her grow.

But I can hardly say what draws me through these pages so hungrily. A man in hiking boots and a dirty t-shirt, rancid shorts, rushing in from a rainforest adventure (crocodiles, scorpions, strangler figs, howler monkeys galore, the most bustling ecology in the world) to see what will happen when Emma’s friend Harriet finds out that Emma has been quite wrong about a certain not very gentlemanly gentleman’s being in love. Talk about bad advice!

Emma is a thinker. Her mind is a war zone. Nothing is black and white, though she likes to start with strict oppositions. Her goal is intelligent love, developed through reason, through the application of character.

Austen leaves a number of suitable men littered about the plot, but one by one they are married off. Emma’s declaration that she will never marry is the engine. It’s like a murder mystery, one suspect eliminated at a time. Emma, despite her fussiness, is so human (full of demons she can’t entirely repress: jealousy, cattiness, hunger, boredom, a touch of wildness) that we care about her deeply, and cannot abide her wish for a life of duty. I rooted for one gentleman, then the next, found my hopes dashed when their character flaws came exposed. I laughed in the face of Mister Elwood, who dared propose. To my Emma! Fool! Just not suitable.

Sex is buried deeply under everything, the only overt mention being something about the saffron robes of Hymen being donned on one’s wedding night, and a certain amount of perspiration on hot days. But then, ah, late in the book, the mere touch of the right gentleman’s hand on dear Emma’s arm? It might be the hottest scene in literature.

Alas, never was there a point in this life at which I’d have been a suitable match for Emma. The only respectable thing I ever did was save her story for my older self. And I must thank my younger–I enjoyed it very much, young man. And just look at all the books you bought me. Far more than a man of my subtly advancing years will ever be able to read.

I love your views on this book. So happy you finally read it!

Now I will read it again — for perhaps the fifth time — and enjoy it all the more for having read this post.

So you did enjoy it. I met my young writers group today (ages 11-15), and one of them told me about a book she’d seen, a zombie Pride and Prejudice! Now we’re talking.

Pride & Prejudice & Zombies *shakes head* it was good for what it was, but it was bad for what it tired to be. At least that’s my take on it.

I had Lionel Trilling @ Columbia College back in the 50’s . He was an exceptional lecturer & teacher. I received a B . In my papers, he liked my content, but not my punctuation.

A grade of B was a big deal back then. This edition is one of the old Riverside books from Houghton Mifflin, beautifully done in 1957. No doubt I found it in one of the used book stores around Union Square, all gone now. Except the Strand, of course. I love Trilling. He was one of the new critics, they still call them. Emma was first published in 1816. Austen died in 1817. But Emma Woodhouse lives!

I love this book. I love this post. I love Bill (particularly elder Bill).

I’m still saving some Shakespeare for my 90s.