Bad Advice Wednesday: Luck and Pluck and WTF (Revisited)

categories: Bad Advice / Cocktail Hour

6 comments

.

I’m still thinking about how much of any career is luck and accident, especially a career in the arts. You get an idea or you don’t. You meet the helpful person or you don’t. You listen to good advice or fail to. You ignore bad advice (or Bad Advice) or don’t. You connect with a mentor or you don’t. You move here, you move there. You’re hired, you’re not. You get a little affirmation, you get a little discouragement, or a lot of one or the other, despite simply being who you are all along. Slowly you learn what you’re good at, but always you insist on trying things you’re not good at, on doing the thing you can’t do, on reaching higher. It’s the Peter Principal applied to the arts, though it’s entirely self-imposed. Call it the Bill-and-Dave’s-Cocktail-Hour Principal: we grow and grow till we get to a place we can’t grow out of.

This week, Bad Advice is interactive. I’m interested in hearing about other people’s trajectories, no matter where you find yourself in your career, or not-career. What did you used to do and what are you doing now to sustain and nurture the writing bug, or the bug in other arts? How’d you get where you are, or aren’t? What did the early years look like? What accidents pushed you this way or that? What makes a reader a reader and a writer a writer? And don’t you have to be a reader to be a writer?

pushed you this way or that? What makes a reader a reader and a writer a writer? And don’t you have to be a reader to be a writer?

Dave’s first installment of “Talking to Ghosts” compellingly visits his literary influences, his mentors, his youthful artistic vision, wonderful. But he was also an Ultimate Frisbee champion–how does that history play into the current work? Or does it?

I was a paperboy for a year or two before I was really old enough to work, a mile or so on my bike each morning. I stocked groceries at the A&P. I cleared brush for a day with my friend Kurt and the lady paid us in Pepperidge Farm Goldfish. I played in bands, good and bad, not very remunerative. I dropped out of college, worked for an electrician for a year of partying, then went back. I used to wake up and worry at night, but now I just lie there and think. I don’t know what accounts for the change. I used to gaze in the mirror for long intervals, trying to see who was there (also secretly vain). Not so much anymore.

For a short time, a season or two, I worked with cattle and sheep and various machines in Nebraska, rode a horse named Bill. In various parts of the country I worked construction a little, then a lot. Sometimes projects come to mind. A fancy staircase. A teak counter. I was a dishwasher for four days once. The owner told us to recycle any decent-looking pickles. I got fired when the cook got fired, because he was a friend of mine. I played in more bands. I was a bartender in a disco for a year, and then at a jazz club, both in Seattle—I used to travel solo. I worked as a waiter in a lunch place for tips only since my whole paycheck was taken up by dishes I broke. I was a musician one place and another, ultimately New York City, which just meant I was sometimes broke. I was a handyman often—just make a poster and tape them up everywhere and wait for the phone to ring. I once painted Barbara Walter’s apartment in Manhattan. She had Egyptian antiquities on display and a poodle that got paint on its butt, big crisis, also a telephone next to her toiwet, first time I ever saw that. I remodeled kitchens and bathrooms all over the city for people who wanted to save money: I underestimated everything drastically. I tiled showers and rooftop patios and the floor of a fancy hot-dog shop. I was asked to build a bar in a bordello, but they wanted to pay in trade. Me, at that age? I needed the money more than what they had to offer. I never wondered what the hell I was doing. I knew what I was doing: I was making money so I could write. That was a romantic notion, too. The artist in his garret. A few dimes here, bowl of gruel. At least I didn’t have tuberculosis. And actually, I lived pretty large–nice big lofts in SoHo then the Meat District, which we called Meat-Ho.

My theory was you had to have experience if you were going to write. I still subscribe to this theory, which doesn’t mean it’s correct. Another theory would be to sit down and write and just keep writing, do and think nothing else. But I’m always telling students to defer grad school till they’re fully broken, to join the Merchant Marine, to quit their jobs, to forestall marriage, to wander far and wide, impress their parents at a later date. For my part, I got good at all kinds of things—cards, pinball, shooting, plumbing, mixology, sailing, gardening, birding, memo-writing—and I did a lot of stuff I don’t do now. I used to fly-fish extensively, for example, and play tennis, play golf, downhill ski, bike to work, go parachuting on a lark, rafting, whatever. I could drive any size truck (but never learned to drive a motorcycle: too scared after my brother’s roommate was killed in a jumping accident). I used to drink large amounts of beer, but became allergic at age 45, go figure. Now it’s Jack Daniel’s or good wine, not such a bad fate. Before I published anything else I wrote a how-to book called Tips and Tricks for Home Repair. It was a contract deal, a work for hire, $2500, a vast fortune at the time. It looked like a phone book, really cheap, illustrated by a film-strip guy, those cheerful stick-figure people pointing out the pliers, thin paper, lots of pages. It was on my resume for a long time, but then I went to grad school and realized it didn’t count. For three lovely years there at Columbia in the City of New York I taught a course called Logic and Rhetoric. Later I taught at the University of Maine at Farmington, then in the grad program at Ohio State. I got tenure there after just two years but found the fact and nature of tenure depressing and kind of medieval and after a while I quit, moved back to Maine. Most recently I taught at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, a five-year position, but now that’s done, twenty years of teaching altogether, yet another thing I was good at and loved and did in order to write, and now have quit in order to write. Till I go broke, that is. Or miss it too much.

All of these things were accidental. I mean, I was handy with tools, so I did construction, which I was not always good at. I found anything outdoors romantic, so I stumbled into one thing after the next, any work, any project, any road trip, farm work, fine, as long as most of it was outside. I was good at the piano, and could sing at least a little, so I played in bands. I was comfortable in front of a classroom—a natural entertainer—and took sustenance from the minds of students, so I taught.

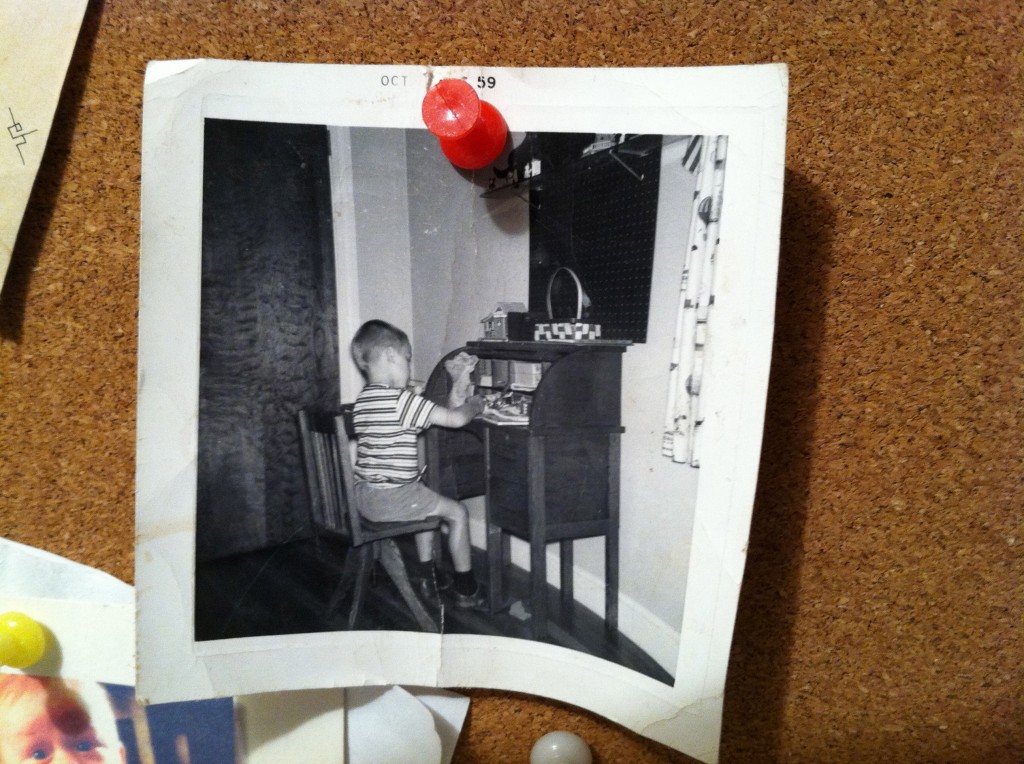

When I was five I asked for a desk for Christmas.

My mother told the story often. Why a desk? she asked.

Because I am going to be a writer, I said.

I don’t understand this. Maybe I knew what a writer was because Mom read to us so much. She’d sit at the kitchen table and read passages from whatever she was reading, didn’t matter. A page from Elmer Gantry. An Ann Landers column, whole. At bedtime she read us the unabridged Gulliver’s Travels, with Gulliver climbing around the cleavage of Brobdingnabian women who thought him a pet, these huge disgusting pores and overpowering perfume and quivering bosoms, illustrations, too, awesome. The desk was a miniature oak roll-top from the Sears Roebuck catalogue. I gave it to my daughter when she was five, and she loved it for a while, but now she’s already too big for it.

And I wrote, another knack, got through High School on bare verbal talent, college the same, though here and there an English or physics or philosophy teacher lit new fires.

No matter what else I was doing, college forward, I was writing. Writing was the thing, writing was the point. I filled notebooks. I subscribed to literary magazines. I wrote two, no three, apprentice novels. I haughtily eschewed writing programs, writing conferences—I can’t quite remember why. I sent stories to the New Yorker and the Paris Review and Raritan and collected mountains of rejection slips.

I read and wrote so much that the guys in one of my bands called me The Professor. This long before I’d even considered such a thing. Everything I did, I did so I could write. I published nothing of substance until I was, like, 35. I still don’t know what kept me going. Bands, maybe. The instant rewards of playing music pretty well in front of crowds, people dancing, yelling. That’s where I could be an artist and hear applause, take home some cash. Just never quite seriously. What was serious was writing. And because I was writing and reading so much I was failing to keep up with my peers in music. Not enough practice, not enough study, not enough focus on the music of the day, the trend-lines, the new equipment, the shifting attitudes, the grimmer lineaments.

And one night in Norway in the back of a friend’s friendly band bus somewhere between Bergen and Stavanger, age thirty or so, I decided I couldn’t do it anymore. The two things, music and writing, they came from the same well, so it seemed. I made a decision, one of the few in life that wasn’t made for me: I quit playing music. I just simply quit.

I was going to write.

How about you? Tell us how you do it, and how you did it, and what you’ve got planned.

[Note: This was my first post on Bill and Dave’s, a little over two years ago. We hadn’t conceived of Bad Advice yet, but this fits into the mold, and I’ve recast it to some degree.]

My first written story was about my Barbie dolls, what they wore, who went to the party and with whom. Second grade. My mom kept it, and I found it not that long ago and had a good laugh.

I always loved to read. I always had stories in my head. I wrote them down. I did receive some encouragement from a wonderful 8th grade teacher (who also ended up teaching Senior English). I decided to go the “safe route” and study education rather than creative writing in college, but I did take an Intro to Fiction class at UMF, had some positive feedback there, published poems and stories in the student mags, but all the while I knew my writing was “missing” something, that literary spark. (Maybe it was all those Barbara Cartland and Danielle Steele books I inhaled at the crucial adolescent age when I should have been reading Mary Shelley or Edith Wharton?)

I know I’m no literary genius and never will be, but I still love writing, still keep at it, but not with the requisite focus and passion that might get me somewhere (wherever that is). I guess I have been able to avoid being bitter by being passive:)

Anyway, I’ve had a few (four) stories published in the confession magazine market the last couple of years and one more “literary-ish” story in an online magazine (chick-lit meets Kafka–heroine turns into a turnip, one of my more inspired moments, I must say). I wrote a couple of romance novels. Got a three-page rejection letter for one, which I chose to view as positive…if only I’d get butt in gear and rewrite the thing! I write a blog about “living locally/sustainably,” and that helps focus creative energies in a positive way.

One last thing: I also learned to knit over the past few years. When I tell people this, no one says to me “Oh, have you sold any sweaters yet?”

Have you sold any sweaters yet? That’s a great observation. If you’re making art, people think you’re nuts if you’re not making money. But if you’re playing soccer, for example, no one asks why you aren’t playing with the Galaxy. Love hearing about your trajectory. Reading, writing, life itself.

From the time I learned to write the alphabet and then to makes words on purpose, I wrote letters. Living in an orphanage with the unwavering but misguided understanding that it was only a temporary arrangement, I wrote long and longing letters to my estranged parents. They seldom wrote back but they did come for visits once in a while. After ten years or so, it became apparent that if I was going to leave the orphanage it was going to be because I was too old to live there anymore.

As a coping mechanism, I made art and music and wrote about everything under the sun. I read about Michelangelo in the Agony and the Ecstacy when I was nine. When I was ten, I wondered why everyone loved Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night and not mine. The nuns applauded my uber achievement at school and discouraged any musician, artist, writer nonsense. My artistic angst prompted them to have my creative expressions analyzed by a mental health professional. I think it was their way of letting me know that intellectuals who dreamt instead of pursuing the arts might be crazy.

After a huge abusive hullaballoo by a drunken nun and her Great Dane dog, I demanded my independence from the institution. The incident was swept quietly under the rug and the state of NJ allowed me to move out. I rented a room in the house of a widow and completed my senior year of high school in the top ten percent of my class a week before I received my letter of emancipation from state wardship. I’d applied to Cooper Union, Pratt, Cornell… Any acceptance letters that may have been forthcoming from the colleges to which I’d applied never managed to find their way to the widow’s mailbox. I was on my own without a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of.

I moved in with a sympathetic aunt and got a job as a truck stop waitress. I bought a 200 dollar beater car and limped my way through the next few years. By the time I was 21, I was piece-mealing formal music studies in NYC, working as a stunt woman in the film industry, and slinging hash on the night shift. I became the girl singer in a country band in the NY metro area, met lots of movers and shakers and turned down two record deals. (Really?, I was clueless.)

The price tag for success was too dear. The casting couch was alive and well and I steered clear of it. I’m sure my career suffered as a result but at least I could sleep (with myself) at the end of the day. Through it all, I wrote. Everyone said I wrote well. “You should be a writer”. I thought that’s what I was doing. It finally dawned on me that you’re only a writer if you’re getting paid to be a writer.

I was selling nice little paintings to make ends meet but eventually was evicted for non-payment of rent and ended up living in my car with my two cats. We shared one can of Friskies Buffet a day. I scavenged through the dumpster behind a little Italian restaurant every night for pizza scraps, cigarette butts and scraps of paper to write and draw on. As hard as it was, art and music were my life, HA! I never thought to myself, “I should have stayed in the orphanage and gone to college to be an English major”, though in hindsight it might have been the prudent thing to do.

Fast forwarding through the years, I made my way, just barely, selling my art, making my music, and reading and writing. I passed up a few good opportunities and I like to tell myself it was because I didn’t know any better. In reality, I was waiting for someone to come along and take good care of me, to tell me what to do, and to tell me my art was worth the sacrifice. It never really happened.

I married later in life and became an “advanced maternal aged” mama (I was 38). My creative sensibilities got stashed in a box along with all my other meager belongings. I retired from the film business, sang just for fun, and immersed myself in domestic routine. It wasn’t long before the pang of artistic longing was too difficult to ignore. I began exploring Japanese poetic genres and have enjoyed at least a semblance of fulfillment there. Then I took the plunge and finally went to college. Got my degree in psychology when I turned fifty and now I’m getting the master’s in transformative arts.

Who knows what’s next? The ghosts of would, shoulda, coulda cannot taunt me. I’ve been in the right place at the wrong time and the wrong place at the right time. I became acquainted with the adage ‘it’s not who you know it’s who you blow” and wouldn’t go there. I did everything I intended to do and in ways that I could live with myself. Whether or not fate intervened is beside the point – I did my thing. I finally learned that approval (as in a paycheck) is only secondary. I’m no better or worse off than those who shook their heads with sanctimonious disapproval at my bohemian approach to life. I enjoyed a modicum of success through expression but the greatest challenge was in deciding which form of artistic expression to focus on. I always wanted to do them all and therein might lie the connundrum.

Katherine–this is an amazing story. And you’ve found your way, amazingly. It’s hard being good at a lot of things, because there are so many good things to do. But most writers are good at everything, and that comes in handy, because it gives you something to write about, and a way to get great at at least one thing: words.

Man, I can’t match the energy here, not today. But what I have just realized, about forty years after first exposure, is what an impact reading everything by and about Hemingway did for me, to me. Why do I want everything to be lyrical? Why does covering narrative ground with one competent sentence after another make me despair? It was his stories and the first chapter of A Farewell to Arms.

I was seen as the family writer, and when I was sixteen or seventeen my big sister gave me a mass market paperback copy of Hochner’s Papa Hemingway. I got the myth there and it propelled me into the work, and I got inside it. Hemingway said building a pedestal is more important than who you put up there, but I disagree. Maybe he said significant, so okay. But although I dislike him now as a person and can’t stand large swaths of his novels, the way he used language in those stories was magical and still haunts me.

Hemingway really got to me. I remember reading The Sun Also Risesunder a tree at Ithaca College for a class. I got to the end and starting over again, nice spring day. He made me nervous even then, bashing his way out of airplanes with his head and shooting everything in sight. I approved of the drinking, however. And tried to emulate him in that and not only the short, declarative sentence (long since abandoned for the complex-compound page burner). I tried to teach that book at Ohio State, remembering my pleasure in it. Several African-American kids refused to read it after the first couple of pages–long emails. I’d forgotten the racism. And the young women really hated it. And not a single person liked it at all. Not that there wasn’t anything to teach in all that. But it’s a book that hasn’t aged well. Not like me! I’m still in love wtih Lady Brett Ashley, and still wish the narrator wasn’t missing that crucial bit of equipment she wouldn’t accept him without. Isn’t it lovely to think so.