Bad Advice Wednesday: Believe in Will (Why Not?)

categories: Cocktail Hour

8 comments

Does such a thing as effort even exist? Or are we humans genetically predisposed toward a certain amount of trying, with the oomph we put into our endeavors as predetermined as our height or eye color? Anyway, don’t most of us try more or less the same amount, with some of us making more of a show of it, like grunting tennis players?

Does such a thing as effort even exist? Or are we humans genetically predisposed toward a certain amount of trying, with the oomph we put into our endeavors as predetermined as our height or eye color? Anyway, don’t most of us try more or less the same amount, with some of us making more of a show of it, like grunting tennis players?

I grew up with a man who was a great believer in effort. Let a basketball bounce out of bounds without diving after it and you found that out pretty quickly Trying was everything and he liked to spell out the word that he believed held the answers to most of life’s questions: “W-O-R-K.” At the same time he abhorred what Red Auerbach called “false hustle.” If you asked him “Is effort predetermined?” he might snort (or maybe, if he were too busy working, just wouldn’t answer).

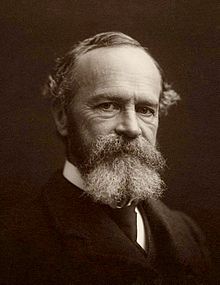

But I have been chewing over this question since I started reading Robert Richardson’s wonderful biography of William James. James–philosopher, teacher, author of the Varieties of Religious Experience, father of modern American psychology–was a contradictory mix of soft and hard, a Harvard professor who attended séances because he didn’t want to exclude any aspect of life, even the possibility of the supernatural, from his thinking. James, born in 1842, invented the phrase “stream of consciousness,” and one of his gifts was for describing certain eddies and backwaters in that stream which we all live in. For instance, Richardson quotes James on the subjective experience of trying to remember a name we know but have forgotten: “There is a gap therein: but no mere gap. It is a gap that is intensely active. A sort of wraith of the name is in it, beckoning us in a given direction, making us at moments tingle with the sense of our closeness, and then letting us sink back without the longed-for term.”

A subtle and playful thinker, James seems at first glance an odd choice to be a great believer in will or effort, and in fact this advocate of habit was surprisingly habit-less himself, taking twenty years to write his first real book. Meanwhile his brother, Henry (whose bio by Leon Edel I am reading concurrently), embodied the notion of effort, focusing in on the task of becoming a great writer like a bulldog (though an effete, Anglophile bulldog), cranking out book after book.

But in the end William James, perhaps because he spent so long brilliantly brooding on the notion of will and perhaps precisely because that for him, unlike his brother, concentrated effort did not come naturally, gave us some of our most profound insights into will. Surprisingly, after all sorts of mental gymnastics, he came around to a philosophy not entirely unlike my father’s. The effort, the act, the gamble, the thrust, was everything. He writes: “We measure ourselves by many standards. Our strength and our intelligence, our wealth and our good luck, are things that warm our heart and make us feel ourselves a match for life. But deeper than all such things, and able to suffice unto itself without them, is the sense of the amount of effort we can put forth…He who can make none is but a shadow; he who can make much is a hero.”

It would be easy to say that Henry James was a maker, while William was a thinker. But William was no slouch as a maker himself, creating books that have lasted, and he also had what Richardson calls “a great experiencing nature.” In his thinking he never strays far from what experience has taught him. Experience has taught him that effort and will are not myths, that at some point ideas and theories must be put aside and a great un-nameable lurch must be made. We feel this on a small scale when we begin anything new. It is a hurling of oneself into the unknown. An effort. Can we control it? Perhaps not but sometimes it feels like the only thing we can control. And it is that feeling that James zones in on. Perhaps it is not true that our effort can have an impact on events, or that we can have an impact on our efforts, but it certainly feels true.

Richardson quotes James: “The deepest question that is ever asked admits of no reply but the dumb turning of the will and the tighteneing of our heart-strings as we say, “Yes, I will even have it so!’” And: “’Will you or won’t you have it so?’” is the most probing question we are ever asked….’” The implication is that the answer “I will” is vastly preferably to “I won’t,” and that we have something to do with which it will be.

If this sounds too vague for an advice column on writing then let me end with this truly good bad advice from Mr. James:

“Sow an action, and you reap a habit; sow a habit and you reap a character; sow a character and you reap a destiny.”

J. C. Hallman also has an interesting book out on the Jameses–Wm & H’ry is about the lifelong correspondence between the brothers and how they influenced one another as thinkers/artists. It’s a small, fascinating book. (Published by Iowa’s Muse Books, and Robert Richardson is the series editor.)

Beautiful and powerful, a fateful combination. The James gang. What a family to have produced such brothers, what brothers!

Very impressive essay . Goes right to the essence of the James brothers w/o any Bull.

Beautiful and profound David , and I think I would have to add passion to will, being driven seems to be the energy beneath will. Passion is some deep vein I see in athletics and strangely in the artist life.(writer.s life?) I think both and the art of words, come from some almost demonic reaching that is almost embarrassing to me. When I have taught I always say to students, art comes at the most inconvenient and embarrassing times. Just get up and make what you are dreaming of and then after you have slept again look at it. If great art came from careful planning and strategy more people would succeed. I watched my husband draw up schemes in the middle of the night like a mad man. I got use to it and then I started to create myself and I suddenly knew what he was doing. Don’t expect anyone to think you are sane when you are in a trance creating your dream. No one will, just spit it out, let it come out of you and then deal with what comes next?

Mike,

Ha! I cranked that little sucker of an essay out this morning and didn’t pause much other than over that line…..I was going to put a parenthetical: (though a hell of maker in his own right). Of course you are right. Richardson makes it very clear that WJ was an artist as much as anything.

Well, I thought I was done with it but will now have to go back and change. Thanks!

Corrections made!

and it is an inspired essay, the way you often do. That is what reading your work so compelling you can feel the will and the intelligence you use to push it forth. Always ready to see what you have waiting for us next.

Great piece. However, I would not so easily categorize WJ (a guiding light for me) as thinker rather than writer. I have never been more deeply and poetically moved by any piece of writing as I was when I read and reread Pragmatism in the desert many years ago. Varieties of Religious Experience always has a place near my bed.