Guest contributor: Thierry Kauffmann

Telling Stories with Music

categories: Cocktail Hour

12 comments

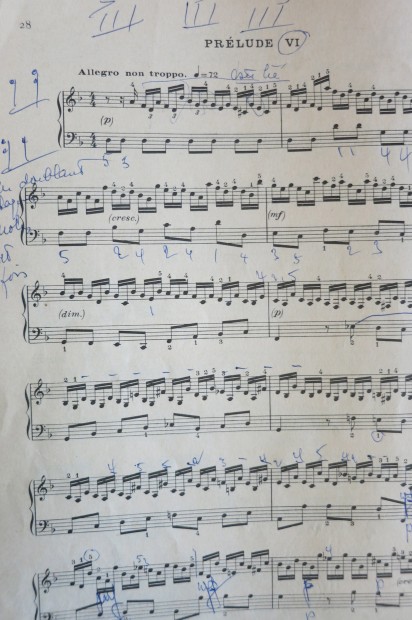

I begin with the old testament, the Well Tempered Clavier from Bach. I play the preludes, because they are all about fire. The melody flows evenly, I might say heavenly. The evenness of sound, the balance of the body and mind that are required to play these pieces, lift me above human condition. If I can do it for one minute, that minute, that condensation of transcendence, is like having breakfast with the divine. Philosophical sounds, is how I call the preludes.

Music is the art of not dying, the art of sustained sound, the craddle of memory. Isolated notes do not last very long, they are like points on a drawing. Sustained sound allows the musician to draw lines, curves, shapes. Lines are story lines, individual plots in a complex novel, whose words are tied to a more ancient, more instinctual language than the words of the writer.

Sounds are signals, they carry immediate information. They act on the emotional system. Accelerated heart beat, sweating, increased blood pressure, are among some of the effects of sounds. Their purpose is to prepare the body for action, by supplying additional energy. Emotion leads to motion.

Blacksmiths make pieces out of metal by banging on them with a hammer. They also make a lot of noise. Two blacksmiths means twice the amount of noise. And that makes perfect sense. Pythagore thought so. Imagine his surprise, when instead of more noise, he heard less. He heard peace.

Pythagore had discovered chords, chords whose notes reinforce each other. Cooperate. Share vibrations with each other. Harmonious. Music could bring peace, and soon, much more. Provided it relied on these building blocks, out of which the entire foundation of classical music would rise. Harmony.

Instruments are characters in the story. They each have their distinct voice.. But unlike narratives, at each time, the superposition of voices must make a chord and that chord cannot be random. Harmonious, yes, but if the piece is in the key of G, dropping a Dsharp chord isn’t going to work. Too strange, too unexpected. Dsharp is simply too far away from G. You need time to get there. Each key is an emotion, and emotions have inertia, unlike thoughts.

So a music piece is a melody and a bass line. The melody proceeds in steps, whereas the bass makes jumps of three and a half steps, the fourth. To combine the evolutin of both melody and bass, is pretty much a mathematical problem. That sets it apart from literary writing, where constraints are not as precise, not as binding.

There is no music without a theme. A vision, powerful and deep enough, to sustain the entire piece. The theme is what keeps the composer going, for the three weeks that the best of them need, to finish their piece. Mozart, Mendelssohn, Gershwin, all finished in three weeks. After that, inspiration goes away, and nothing can bring it back.

There is a map, linking chords and feelings, but that map is more a holy grail, then something you can buy in a store. That map is implicit, and requires experience to recognize. So much depends on which instrument plays what, that is, not just on the note, but on the harmonic content of each instrument. How many harmonics, and how they are set to interact, conveys extremely subtle messages that somehow our brain perceives.

That map is more a map between chord progressions, and changes in emotions. An emotional journey, a song, or a longer piece, can thus be coded, writen, in musical form.

My grandparents married in 1929. It was a grand wedding, which took place in an old church sitting on a hill above the Isere river. My great grand father hired two camera operators from the Pathe Company. Recently, the resulting 9 1/2 mm film was given by my parents to a store specializing in digital transfer. The film came back with music mixed with it. It sounded like Circus music. I bought a video editing software, removed the offending soundtrack, slowed the film down to make it easier for us to see more clearly all the family and friends who attended the wedding. The film was now fifteen minute long. Fifteen minutes of silence.

One morning, over breakfast, I told my parents I would write music for this film. After a few trials, I realized nothing less than Bach would fit. And it would have to be me composing as if I were Bach.

Christmas was just around the corner, there was no time to waste. I sat at the piano, and hit a wall for thirty minutes in a row, incapable of understanding which chord progression to use, for how long, at what speed.

I could tell when I was off course, usually after the first turn. Wrong key. I would then go back to a similar piece by Bach, find my error, and discover many more. Mostly my rhythm would be wrong. Bach never plays 4/4 straight, but instead shifts the strong beat around in a seemingly unpredictable way, always landing on his feet. As for me, I would miss every other shift. Twenty minutes of that exercise would leave me exhausted, our of breath and neurons.

You can hear the result here. Almost as important, is what I cut from this piece. For music, like mathematics, is based on rules, not about what to compose, but about all the things you cannot do, while composing.

Music, like spoken poetry, is built for transmission of knowledge, for it triggers a strong emotional reaction which facilitates memorization. Memorization, in the age of few books, was a subject primary importance during the middle ages. Spatial techniques were found, to assist in that process. Here is how it works. Let’s say you want to remember, and by that I mean you must remember, twenty four chapters of a book. You would learn each chapter in a different room, so as to associate room and chapter in a visual way. To remember the book, all you would need is a map, the list of rooms to visit, and the order in which you would visit them. And these rooms were positioned to form a geometric figure, a highly symmetric figure, one that would itself be easy to remember.

You can think of the reader moving from room to room as some kind of a dance. Like hopscotch. The space for this dance is no longer continuous. You’re constrained to be in a room. There is nothing “between” rooms.

You can also think of the rooms as keys and their associated scales. Twelve major, and twelve minor scales. This is one of the many ways in which music mirrors dance and vice versa. But it points to a deep connection between memory and music, and oral poetry.

As we know, writing came late, long after spoken language. It also came through numbers. Cuneiform writing was created by merchants who exchanged goods and needed to do reliable accounting. To express that seven sheep had been sold, they would put seven clay token into a clay container, sealed it, and impressed a nail onto the clay container for each token inside. Later on, clay tablets came to replace containers. They were rarely fired into a kiln, because they were not conceived as permanent. Thanks to invasions, scores of tablets were found, after the tablets burned with the city itself.

At that time, around 3000 BC, in Mesopotamia, there was a direct link between writing and so-called natural numbers, that is integers. Numbers gave rise to letters, and certain traditions make use of that correspondance.

At that time, around 3000 BC, in Mesopotamia, there was a direct link between writing and so-called natural numbers, that is integers. Numbers gave rise to letters, and certain traditions make use of that correspondance.

In writing, as in life, I like simplicity. I imagine, I see, a quiet village in rural France, around noon. Platane trees stand around the main square. A small fountain sits in its center, it is one hundred years old. The sound of the water trickling out of the iron nozzle spreads to the surrounding streets. Its peaceful chatter fills the hours evenly, giving the traveler a place to rest, refresh, and repair.

Only the lengthening of shadows, and the tinkle of the church bell, reaching as far as the nearby fields, seem to know that time still exists. I could stay there forever. Maybe I already did.

If I didn’t have words, if I only had a piano, how would I render this scene?

Let us find out. The first thing I did, is to find the key, the unique key for this piece. A key divides the keyboard in two, the lows and the highs. With each step up, or down, the emotional content of notes changes. Each note is interpreted in reference to human sounds of same pitch. I chose D maj.

Because the peace in this text, has always been there, and has not been fought for, or conquered, I wanted to step away from the classical dramatic construction, with its sharply contrasting major and minor key. Seventh chords, are quietly major, not openly, nor blaringly. They are unresolved. At the same time, they contain no tension. I thought about Jango Rheinhard, and played with it. The text also has no time scale, which I tried to convey with free form.

Writing, with its infinite vocabulary, can reach farther into the human condition. Less constrained than music, more free, it is not easier, for constraints actually help. The less choice you have, the faster you decide.

Music progression, as far as western music is concerned, is based on the brain’s need for closure, or resolution. That is the return to the original key of the piece.

A story is then told by successive explorations of neighborhing keys, including minor keys, and by the accumulation of tension, expressed by dissonant chords, such as augmented 7th, and which mirrors the torment inside the heroes heart as he faces increasing obstacles in his quest. More and more instruments join, playing the theme in turn. Forces, fragmented, dissonant, align with each other, a current of harmony lifts the hero above darkness, light is reached, the climax, and a fireworks of arpeggios spreads from both ends of the scale, it’s the catharsis, a big bang in reverse, the final explosion of the hero, into being.

You can listen here.

[Bio: I was born in a state of grace. I heard music and I counted numbers all day long. In school I improvised stories. Before the age of 30 I moved to the US where I taught science and learned modern dance. I was a financial analyst when the bell rang: I had been diagnosed with Parkinson. I am now writing a memoir of my journey, combining science, music, and illness. My first story was published by Bill and Dave’s. Two other stories appeared in Nib magazine. I live in my hometown in France with my parents.]

Wow. Blown away. You made a non-musical person understand. Tres bien!

And yes, though constraints make your life easier, they do also force you to come up with creative ways to accomplish what you want within them. Scorsese’s best work came (in my opinion) in the 70’s when he did have constraints on him, before he could do whatever he wished. So you have everything to be proud of.

In any case, this was gorgeous. And we want more.

Well-said, V, as usual, well-said!

Thank you Vasilios. Being understood by non-musicians was one of my constraints…I appreciate your comment. I do have more writing coming.

“To combine the evolution of both melody and bass, is pretty much a mathematical problem. That sets it apart from literary writing, where constraints are not as precise, not as binding.”

Ah yes, this is very true of literary writing. Constraints…It’s hard to breathe thinking about all the living examples and implications. No wonder writing feels right. I have become better at mathematical points–very useful! But still, don’t ever let me pick up a musical instrument. Even a tambourine becomes obnoxious in my enthusiasm for all those pretty, fluttering cymbals. What a gift you have! I enjoyed your essay and thinking about music.

Oh, I forgot to say that of all the many Best Days of my life, 5 were in Paris! I love the photo of your home.

Debora, I wish it was my home! Mine is smaller…But thank you!

Debora: Thank you for your comments. I enjoy reading your experience too.

Bill and Dave’s fans, we’re in the presence of greatness.

Merci Tommy.

I couldn’t type well yesterday. I am touched by your comment Tommy. I intend to write more on this subject.

Lovely music. Thank you.

Janine, I’m glad you enjoyed the piece.