Table for Two: An Interview with Monica Wood

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

7 comments

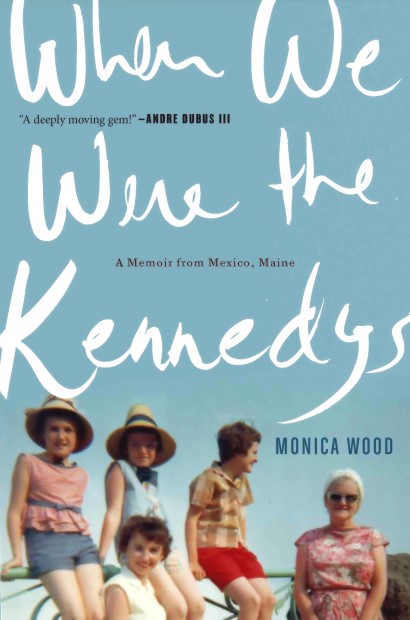

Monica Woods’s new book, When We Were the Kennedys, is being published this week by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. It’s a superb book, warm and funny and wise and heartbreaking, too, the story of a terrible year in a wonderful life, the year Monica’s father died when she was just nine. And wait—it’s not an entirely terrible year, full of the life of a busy mill town in Maine, the life of a big female family, the life of a country about to lose its president, and the life of a very observant protagonist.

Monica is the author of four works of fiction, most recently Any Bitter Thing, which spent twenty-one weeks on the American Booksellers Association extended bestseller list and was named a Book Sense Top Ten pick. Her other fiction includes Ernie’s Ark, Secret Language, and My Only Story, a finalist for the Kate Chopin Award. She has also won the Bill and Dave’s award for all around agreeableness and great sentences. Her grammar, thanks to her sister Anne, is flawless.

Monica has contributed to our pages, as you know, but we’ve also been friends a long time. She has no brothers her own age, so Dave and I have to do. She only lives in Portland (the one in Maine), an hour and three-quarters away, but it’s proved difficult to get together for a meal and an interview, my fault entirely, busy days of summer. So, as usual, we’re going to make up a meal, just pretend. This one though, at my house here in Farmington, is going to happen on Friday. I mean actually. But now I won’t be obnoxiously interviewing my old friend as we eat, but merely dishing and comparing notes, getting her wisdom, as this interview will have already been published: she’s two full days older than I, and the wisdom she dispenses is indispensible. If that makes any sense.

Friday she’s reading at Devanney, Doak, and Garrett, Booksellers also here in Farmington, thus the actual dinner date, hooray. I’ll be able to see a little of the reading, which starts at seven (be there, Farmingtonians!) but my daughter’s theater camp play opening night—Alice in Wonderland—starts at 7:30 (be there, too! But on Saturday evening or Sunday afternoon), and so I’ll have to slip out.

I’ve been cooking all day and have barely had time to freshen up when Monica arrives, looking sharp as always, like Jackie Kennedy would have looked if Jackie had had any taste. Monica gives me the once over, very pleased with my new pink shirt, oxford collar, button-down and so crisp it crackles when I hug her. Her smile is enough to send me back to Brooks Brothers for more pink shirts, and possibly pink pants as well, and one of those cloth belts with the whales on it. I give her a tour of the premises, and she is gracious. Finally, we sit to dinner on the porch.

Monica: Did you comb your hair?

Bill (unfazed, hair flying): I first heard elements of the first chapter of When We Were the Kennedys when you read an essay called “My Mexico” at the Portland Public Library a couple of years back. I thought of the essay often afterwards, the most vivid possible story of the day of your father’s death (when you were only nine) couched in a portrait of your hometown, which is Mexico, Maine, and in the atmosphere of the era, which was the early ‘sixties. I was struck by all the ways the essay needed to shift and grow to become the first chapter of this memoir, to attain forward momentum, for one thing, but also to announce the very high stakes for this book. Could you tell us a little or a lot about how When We Were the Kennedys came about and how it grew?

Monica: The book did begin as that essay Wes McNair badgered me into writing for his anthology A PLACE CALLED MAINE. He’d been insisting for a while that I had a story about Mexico, Maine, in me somewhere. He insisted; I resisted. But Wes is hard to say no to, so I did write an essay called “My Mexico” that became the germ of WHEN WE WERE THE KENNEDYS. Then I went through a really bad stretch—two friends died, my father-in-law died, a beloved cat died, and then—last straw—a novel I’d spent three years on died. I just wanted to curl up and “go home,” metaphorically speaking, so I did the next best thing: Started writing about home.

Bill: How did it feel to be writing something so different from your usual?

Monica: I was pretty allergic to the whole idea of memoir. For months I called it “a nonfiction thing about my family.” I was embarrassed to be writing about myself, and I had no intention of publishing it. But then I got interested: there was so much I didn’t/couldn’t know about the larger circumstances surrounding Dad’s sudden death, so I started writing a much bigger story, about the impending “death” of bigger things than one ordinary father in an ordinary family. The paper mill was bracing for a strike, and the glamorous Kennedy presidency came to a sudden, murderous end. I spent every Thursday for a while rummaging around in a tiny room in the Rumford town hall, home of the Rumford Historical Society, run by two lovely older women, one of who hailed from Prince Edward Island and talked exactly the way my father had. I looked at letters, photos, newsletters from the mill at different stages; I read every copy of the Rumford Falls Times from around 1955 to 1970. It was all so fascinating. I did more research for this nonfiction book than for all my fiction put together.

Bill: How long did you work at this phase?

Monica: The first draft, which took a year, was fairly journalistic, all narrative, no scene. I believed that “recreating” scenes would be a cheat somehow. But my sister Cathe read it and said, “You’re not even in this. How can you write a memoir that you’re not even in?” Ah, good point. So, in draft two, I started writing like the novelist I am, transforming the material to scene-scene-scene with forward motion and character development, as if these people were characters in a novel. When my sister read it again, she said, “NOW it feels true.”

Bill: So, do you find that your ideas about memoir and truth have changed?

Monica: I’m still pretty traditionalist when it comes to composite characters, altered chronology, things like that. But what I realized is that storytelling—whether in a book or sitting around a kitchen table—is as much about what you leave out as what you put in. You are constantly shaping your story, and stories change over time, often unwittingly. Human memory is a slippery customer. I vowed to do the best I could, but telling “true” stories is like dropping an expensive mosaic and smashing it to pieces, then painstakingly putting it back together so it looks as close to what you remember as possible. “Close” won’t be “exact.” But as long as you go in with a truthful, open heart, your reader will know you did your best.

Bill: Tell us a little about Mexico, Maine, then and now. It’s such a central image in your book, really a character.

Monica: Back then: thriving mill-town community, many languages, lots of stores and businesses. Now: some businesses still there, but also boarded up storefronts, the mill a shadow of its former self, economically depressed. But it’s still home. I still have family there, and old friends. I was just there last weekend. There are signs of hope, but it’s going to be a while, if ever, before it resembles its prosperous past.

Bill: Did anyone ever make the mistake of thinking you were from the other Mexico and, like, introduce you in Spanish?

Monica: No, but Dan, my husband…

Bill: Your devoted, terrific husband…

Monica: Dan once had to explain to a student, when he was jokingly referring to his wife from Mexico, an inferior place (he’s from Rumford, an old rivalry)–the student, shocked, said, “What do you have against Mexicans?” Also, my college friends called me “the girl from Spain, Maine.”

Bill: I love the bridge your father would walk over to get to work across the mighty Androscoggin! And the mill, another central image and character, wow. It gaveth and it tooketh away. Could you read a passage about it?

Monica (accepting the copy of her book I’ve been carrying around and opening it, not at all reticent, since this isn’t really happening): This is from the Epilogue:

“As I return here now, passing the WELCOME TO MEXICO sign, I see up ahead my father’s ghost on the footbridge, his dusty boots, his cap and pail… The cleaned-up river makes its old ribboning trail. The mill—now, as then—hunkers on the riverbank, outsize witness to my childhood. The Oxford, with its bruising power to give and take, was my first metaphor. I pull over to give it a good look.

I was there, it tells me, still pushing smoke signals into the sky. Beneath those clouds, I experienced the shock of loss, the solace of family, the consolation of friendship, the power of words, the comfort of place. Beneath those clouds, I learned that there is, as my birthday Bible instructed me at age ten, a time for every season. Beneath those clouds, my parents died before their time. But they lived here, too, thankful for their chance.”

Bill: Mmm. Your people are so vivid, so moving, so individual. You let us love your uncle, Father Bob, just as you loved him when you were a kid, his flaws only growing apparent gradually, and in a way that only makes us love him more. Your sisters are sources of both drama and humor, provide the kind of backbone to the book that they provided the family in life. Your mother is a wonderful figure, heartbroken and adrift, but always in possession of a deep fund of love and attention, plain competence. There are neighbors here, and hilariously awful landlords. Tell us a little about how you make your people. Is it a different process from character in fiction?

Monica: In the first draft of this book I was so afraid of embellishment that the “characters” were all dead on arrival. All narrative, no scene. I feared that “recreating” scenes would be a cheat somehow. But my sister Cathe read it and said, “You’re not even in this. How can you write a memoir that you’re not even in?” Ah, good point. My sister gave me permission to go back and make characters out of us, to reconstruct the love and hilarity, to make the reader fully know us. So, in draft two, I started writing like the novelist I am, transforming the material to scene-scene-scene with forward motion and character development, as if these people were characters in a novel. When my sister read it again, she said, “NOW it feels true.”

Bill: Funny how facts don’t always add up to the truth.

Monica: Because memories aren’t facts.

Bill: Your Dad’s memory looms and lingers, always a nine-year-old’s dad, supervising a whole corner of the mill during difficult times. He’s a bridge between labor and management, a bridge between Canada and the U.S., he’s a bridge between now and then, and finally a bridge in the book between life and death. I found myself relating to young Monica, of course, and to all those left behind, but—maybe because my daughter’s eleven—I couldn’t stop thinking of your Dad, walking in his shoes. Was it very difficult to evoke him?

Monica: No. It was easy. If you dropped dead today, Bill, your little daughter would remember the essence of you, the invisible stuff. You would live forever as the perfect dad. Everyone I know who lost a parent young tells me this.

Bill: I think I’ve already lived past the perfect dad stage.

Monica: That’s not what I heard.

Bill: Aw.

Monica: Plus you are quite a chef.

Bill: I wrote the line above and put it in your mouth, if that’s what you mean by chef.

Monica: Something doesn’t feel real here.

Bill: Anyway, one of the perks of the plant was the free reams of beautiful Oxford paper, a weekly supply, if I’ve got it right. Heartbreaking when it runs out—the kid you were having no idea that the stuff could be had at stores. I like the quiet way you use the paper to start to make a portrait of the artist as a young girl.

Monica: Yes, the education of a writer is a subtle thread throughout. I didn’t want to appear grandiose, so it’s pretty embedded, but it’s also very important. If my father had not died, would I have become a writer? Honestly, I don’t know.

Bill: You were certainly a reader, and are. Did I notice a nod to Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried in a section about the mill?

Monica: You have the eyes of a hawk, my friend, but it was the section about moving from the place we’d called home for so long, a litany of the things we carried from one place to another: the birdcage, the turkey pan, three eight-pound cats. That litany says it all, about who we were, what we cherished.

Bill: And you have a dazzling way of incorporating your research. Historical society, library, completely seamless. Did you interview people back home? Co-workers of your dad’s, for example?

Monica: Oh, Bill, I met a lovely man, named Bunny Carver, who’d worked with my dad and worshipped him. I went to his house, told him who I was, and he just looked at me as if I were nine and said, “One of Red’s girls.” I could barely keep it together. He died before he could see his name in the acknowledgments, but I sent a book to his widow. He gave me the scene from the workers’ perspective—which I’d never considered—about how it felt to lose their guy, what they were doing on that morning when the word came in that Red had died.

Bill: Tell us about your writing day.

Monica: Lately? Much housecleaning. Usually: three or four hours in my studio. Boring. Predictable.

Bill: But that studio is great. Dan built it for you, right? I remember the white-board on the wall, all your notes on this and that character, and a big desk, and books.

Monica: And many talismans: a homemade wind chime from my friend Patrick, for example, which I’ve had for 25 years.

Bill: And (after you finish enjoying that bite of whatever it is I’ve decided to cook for you tomorrow), since a lot of aspiring writers read these interviews, could you tell us a little about your career? How did you move from reams of free Oxford paper to young novelist to memoirist?

Monica: Same story: great teachers. My sister Anne, for one, who taught English at Mexico High School.

Bill: She’s one of the most delightful characters in the book, the family backbone, it seems. Plus, her more recent history provides a surprising and very cheerful ending for your book, which I won’t give away. But keep going.

Monica: In college I started out as a French major, then switched at the behest of a teacher who ordered me to write. After that, not much writing, until I was about 30 and went to the Stonecoast Writers Conference [link] in Brunswick, Maine, and in two weeks learned the nuts and bolts of fiction writing. That was the sum total of my “training.” Then many years of rejection, rejection, rejection, then my first novel at 40, then a bunch of books in my 40’s, and now as I stare down my late fifties, I have come to this: the book I’ve been headed toward all this time.

Bill: How did all that rejection feel?

Monica: Just wonderful, thanks. Wonderful.

Bill: I know. That’s what makes us writers. A capacity for suffering. One of your books was mis-bound with pages from another book, true? Is that a story you want to tell?

Monica: OH MY GOSH! That was the first paperback edition of Ernie’s Ark, which had—in place of a heartwarming story about an eighth-grader who tries to volunteer during a mill strike—30 pages of a suicide manual called Final Exit. Illustrated!!! My editor literally screamed when I called to tell her.

Bill: And didn’t, like, the production editor at your press say something like, Well, it’s no big deal. We’ll sell out the printing?

Monica: Hah! They recalled every single book from every store and distributer, and “lost” the defaced copy that I had, since I stupidly sent it to them when they asked for it. A year later they re-published the book as if nothing happened.

Bill: So what’s next?

Monica: Nice shirt. I TOLD you you’d look great in pink.

Bill: I got sauce on it. Damn. Monica, thanks. Let’s go watch that video your publisher made about When We Were the Kennedys, and then get you to your reading, 7:30, Devanney, Doak, and Garrett, Booksellers, right on Broadway in Farmington. And by the way, congrats on making it to Broadway!

[Here’s Monica’s tour schedule thus far. Go see a great reader perform!:

Mon, July 9: TV news show “207” on Maine NBC affiliate stations. 7pm

Tue, July 10: Book launch at Longfellow Books, Portland, ME. 7pm

Thu, July 12: Book talk/signing at Kennebooks, Kennebunk, ME. 7pm

Fri, July 13: Book talk/signing at Devaney, Doak & Garrett, Farmington, ME. 7pm

Sat, July 14: “Books in Boothbay,” Railway Village, Boothbay, ME. 12:30-3:30

Mon, July 16: “Literary New England” radio show. 8:15pm EST

Tue, July 17: Book talk at Falmouth Library, Falmouth, ME. Noon.

Tue, July 17: Reading at Stonecoast Writers’ Conference. 3:45pm

Wed, July 18: Book talk/signing at Witherle Library, Castine, ME. 7pm

Thu, July 19: Book talk at Skidompha Libary, Damariscotta, ME. 10am

Thu, July 19: Book signing at Maine Coast Books, Damariscotta, ME. 11-2

Tue, July 24: Book talk/signing at River Run Books, Portsmouth, NH. 7pm

Wed, July 25: Book talk/signing at Portland Public Library, Portland, ME. 12 noon

Thu, July 26: Book talk/signing at Union Church, Biddeford Pool, ME. 7:30pm

Fri, July 27: Book talk/signing at Left Bank books, Belfast, ME. 7pm

Sun, July 29: Graves Library, Kennebunkport, ME. 2pm

Aug 7: Book talk/signing, A Great Good Place for Books, Oakland, CA. 7pm

Aug 8: Store visit, Book Passage, Corte Madera, CA. Noon.

Aug 8: Book talk/signing, Copperfield’s, Santa Rosa, CA. 6pm

Aug 9: Book talk/signing, Books Inc, Berkeley, CA. 7pm

Aug 14: Book talk/signing, Politics & Prose, Washington, DC. 7pm

Aug 26 – Sept 1: Memoir workshop at Haystack Mountain School for the Arts. (FMI go to haystack-mtn.org)

Sept 6: “Meet the Author” talk. Darien Library, Darien, CT. 7pm

Sept 19: Book talk at Rumford Historical Society, Rumford, ME. 7pm]

I’m back

What a charming talk–lively and informational. And, of course, funny. Bill and Monica seem to take inspiration from the same Muse.

Love it, and can’t wait to read the memoir. It’s interesting how switching to nonfiction was such a learning curve for you, Monica, after all your experience. It sounds like you had to feel you’d earned the right to use all your craft, bring it to bear, on your own true story.

Yes, Richard. I think it was about “earning” the right to tell my own story. I had the experience, but not the confidence.

Bill, you are deary-dear. And I don’t believe for one second that you bought a pink shirt.

yellow?

Bill, please. Yellow would be your worst color.