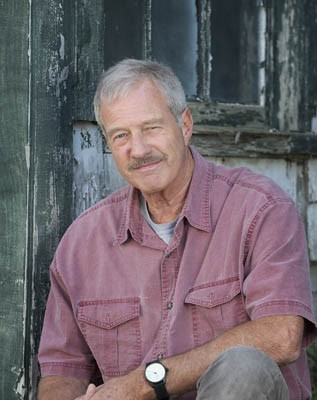

Guest contributor: Debora Black

Table For Two: An Interview with Jim Nichols

categories: Cocktail Hour / Table For Two: Interviews

Comments Off on Table For Two: An Interview with Jim Nichols

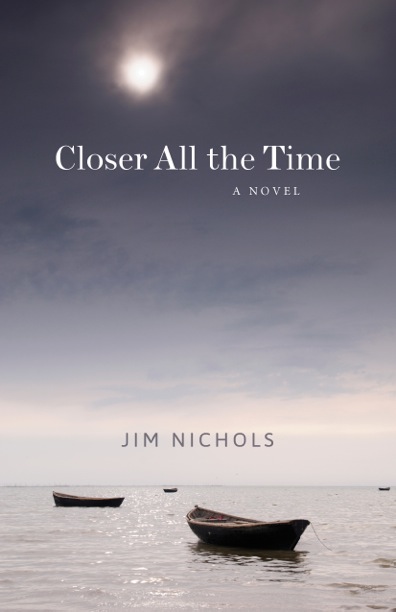

Debora: Jim it’s lovely to have you with us at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour. Congratulations on your new novel Closer All the Time, published by Islandport Press, available now—and at last, for established Jim Nichols fans! I’m a newcomer, Jim, and wish to say that I love this book for the tenderness in the writing and the expressiveness of the characters. It’s clear that there is a lot of experience and wisdom behind these pages.

Jim: Hi Debora, it’s a pleasure to discuss CATT with you and to be part of Bill & Dave’s…one of my very favorite literary sites. And thanks for the kind words, I’m really happy you enjoyed the book.

Debora: I did very much, there is a sensitivity in your portrayal—in the soft descriptions, in the story-by-story treatment of all the characters, in the isolating condition of small-town life. I find it to be a bit poetic, certainly soulful. Tell me though, what do you think about the end result? How would you describe what you have captured and how you got there?

Jim: I like the way it worked out. I think connecting the stories made for a much more unified book. Originally the chapters were independent stories, and at the suggestion of my editor at Islandport (Genevieve Morgan) I rewrote them with recurring characters and situations, and put them all into the same town. Oh, and made a river run through it (grin). I’m not sure the isolation of individuals is a small town attribute, though; maybe because there are fewer people involved it seems that way in a novel. Maybe you can single out characters more easily. But I think people everywhere are always struggling for connections, don’t you?

Debora: Yes, I do. I also think there is something to what you say about how the reader can single out characters more easily. The structure of your book is interesting, Jim, not only in the way you give entire chapters to the principal characters, but also in that these characters vary in age and make their first appearances in another character’s chapter—and in some sort of plot relationship to that character—and then as you mention, each makes recurring appearances thereafter. I like the circling effect this has on moving us through time and plot. All of this had me very involved with each individual and also their importance—their impact—as a member of the town. The other thing happening with point of view is that it shifts between third and first person. How did you determine whose story should be told in third verses first person? How did this serve the novel as a whole?

Jim: Well, for the most part I left the stories written in third person alone, because I thought a sort of unifying narrative voice would help turn these heretofore independent chunks into a novel-in-stories. If I remember right, I changed a couple into third for that reason. But there were certain chapters/stories that simply insisted on being told in the character’s actual voice. Early Blake’s chapter – one of three I wrote to plug gaps during the book’s conversion – appeared in a sort of Morgan Freeman voice that just carried it along, I couldn’t think of taking that away. Another was Arnold’s grownup chapter, and I was just really interested in hearing him speak, after telling his first story in third person. I wanted to listen to what he had to say.

Debora: This is your third book of fiction. And you have also authored many short stories. Do you know the total count? Among these works are numerous accolades, as well. Will you take a moment to provide us with some of the details of your successes?

Jim: Not a huge amount, actually, maybe 35 or 40 stories. I write all the time, but I’m not the most efficient at actually finishing things. But I have published in a couple dozen magazines, and have been lucky enough to receive several prizes, including the Willamette Award in Fiction and the Curt Johnson Prose Award for Fiction. I’ve been a finalist at magazines like Narrative and Glimmer Train and Prime Number. Also, my previous novel (Hull Creek) was runner-up for fiction at the 2012 Maine Book Awards, and won a silver medal IPPY award for regional fiction. Thanks for letting me grandstand a bit!

Debora: Well it’s well deserved, but I forced you, so it doesn’t count as grandstanding. Plus I was leading up to this question. As you look across all of these books and stories, has your writing changed? Are there any steadfast consistencies that typify your work?

Jim: I think and hope I’ve gotten better and more patient with it. As far as consistencies, I’ve always wanted to have a strong narrative voice that comes out of the characters’ own idiom. I have nothing against more sumptuous prose, as long as it relates to the characters’ own hearts and minds, but my own characters tend to be plain-spoken and direct. That doesn’t mean they can’t come out with an elegant turn of phrase from time to time, or that the narrator can’t.

Debora: Yes, those elegant turns account for the poetic feel that I mentioned. Do you have any specific intentions as a writer?

Jim: I’ve had people – including fellow writers – tell me that my work opened up new worlds to them, introduced them to people they hadn’t really thought about before. I think maybe my niche is to tell stories from this community: working class, small-town, sort of rural, independent, generally quiet. They don’t get that much literary attention, but I think there’s plenty of triumph and tragedy – sometimes quiet, sometimes not so much – to find within their lives. I think plenty goes on that maybe isn’t headline material, but that matters just as much as anything else.

Debora: Jim, since you are a Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour fan, you are aware that many of our readers are writers yet aspiring to craft their first complete pieces and also writers who are a little further along and landing their first publications. We would love to hear about what writing has meant to you over your years at the keyboard.

Jim: Well, it’s everything to me. I believe fiction is where truth really lives, and sometimes, if you work hard enough and are lucky, you might find a piece of it for yourself. You might stumble into something universal and manage to capture it well enough that someone else, reading it, will possibly nod their head and smile with recognition.

Debora: I’ve been away from your novel for days, and I’ve still got Tomi Lambert on my mind. You portray her so beautifully—in that soft-handed, sensitive way. As a girl of, what was she, 12? 14? She was such a bright light—free and smart, modest, kind, and on the go. And then the adult version, divorced, waiting tables, being rather objectified by all the males in town—everyone wishing they had a piece of her. She doesn’t seem aware of her light. I was surprised and a little disappointed to find Tomi in Baxter at all.

Jim: Don’t give up on her, Debora…Tomi’s got moxie and she’s still young. She’s a product of her upbringing, of course, and her time, and her small town, and she wasn’t looking very far ahead when she ran off and got married. But I think she grew, realized she deserved better and got out of that situation. Now she’s getting by, raising her girls, marking time maybe, but she’s still Tomi, I hope you can tell by the weary-but-witty remarks. She’ll be fine, it’s just going to take a little while because she has responsibilities and she’s not one to shirk them.

Debora: Actually, I do agree, Tomi is stellar in this moment and consistent with her character. I think it was the way she was involved with those photographs. Something penetrated. So I was surprised. However one thing that strikes me here, goes back to the notion of the way your structure so distinctly brings forward each character. Although we get to see Johnny—the most main character—evolve more completely than the others, we don’t get to see the other characters in quite that same start to finish. I’m not saying we should, it’s as you say—lives have stages and moments, and as we enter and exit these stories, the characters are at various places. But I have a lingering curiosity about them. I mean, look at Arnold! What a state he’s in! Do you feel any similar lingering sense of attachment to these stories? Have you considered writing a second book that continues with the same characters? Or is this a horrible idea?

Jim: I think that’s a great idea. I’d like to find out what happens to Arnold and Tomi, too

Debora: Let’s go back. You’ve just finished writing the book. I’m imagining that you feel a heaping sense of that Ta-dah! I did it! I love it! But your editor makes the suggestion that you go back in, that you take your short stories and thread the characters and events together. What did you feel in that moment? What was your gut reaction and what did you do from there? Which version do you like better—because I can see how the original set-up would work too.

Jim: Well, first off, I didn’t actually write it as a book. These were stories that I’d written individually and sent out to magazines, and after I’d had several published I thought I’d round them up and submit them as a collection. That’s how I’d done it with my first book, Slow Monkeys. But yeah, at that point I thought I was done, so to be asked to rewrite it as a novel gave me pause. It meant taking up the yoke again when I was ready to go back to the first draft of another novel I was working on. But the more I thought about it, the better I liked the idea. Genevieve’s notion of a more unified book sort of took hold, and I started to see associations and threads, how a person in this story could be an earlier version of a character in another story, that sort of thing. I got intrigued with making it work. It was a challenge. So I dove in, and five months later, resubmitted it. I like it lots better this way, so I’m glad it happened.

Debora: Jim what happens in a different set of circumstances when you think over and tryout an editor’s idea, but you end-up not liking it? How do writers and editors deal with that?

Jim: The only other time that’s really happened is when I was asked to swap the first chapter of Hull Creek with a later, more dramatic chapter (about a smuggling trip). I didn’t like the idea because it meant I had to start out with something I’d built up to before, and then change the 2nd, 3rd and 4th chapters into flashbacks, and then when I got to the 5th chapter transition back to present-time with no more flashbacks. I think in that case the book might have been better as it was originally laid out, there was a carefully-designed arc that was disrupted for a while, but the idea of a more dynamic beginning also had its merits, and I wasn’t sure enough that I was right to fight about it. It seemed to work pretty well as it turned out, at least as far as I heard.

Debora: What values and moral code do you live by?

Jim: You should probably have phrased that try to live by (grin). But that said, Do unto others… is as good a place to start as any. Empathy!

Debora: You were raised in a small, blue-collar town. What was your family like when you were growing-up?

Jim: My father was a WWII fighter pilot. My mother – an Army Nurse – married him after her first husband, also a pilot, was shot down and killed over the Istrian Peninsula (a la Tomi’s mother). So you can see I come from fearless stock. I was one of nine children, a rambunctious gang living out in the country. Five boys and four girls and we were our own best friends. We spent most of our time outdoors, but we were also all bookworms and had to be told to turn our lights out most every night. When my mother took us to church (she was French-Irish and Catholic) we occupied a whole pew. My father didn’t go because he was agnostic, and we kids inherited some of his skepticism and didn’t take the services all that seriously. Sometimes we’d sing just slightly off-key during the hymns to try and make each other laugh.

Debora: Sounds wonderful, Jim. You portray a similar sense of well-being within the town of Baxter. Describe what Baxter shows us. Because while I felt this well-being, I also felt—say in the cases of Larry and Sarah, a sense of constriction and disconnection—and in the scenes where the fishermen are competing for their catch and the cabbies are competing for clients—a sense of grating and limitation, like everybody is getting in the way of one another.

Jim: I think you’re right that there’s crowding and impingement because of the small scale of life in Baxter. It’s like one neighborhood, where people always know your business…take Johnny not wanting to walk home from a bar partly because someone might stop and offer him a ride, and then they’d know he’d fallen off the wagon. So right, there’s not the protecting anonymity you can find in a bigger place. But there’s plenty of warmth in Baxter, too. You have families laughing at Martian tales, a father and son racing toward home. And rosy-cheeked kids waiting for school buses, and lonely little boys meeting beautiful girls from Russia! There are centenarians joking about fishing, an adolescent’s first bewildering but thrilling kiss. And isn’t it joy that Johnny feels at the very end, riding with Early and James and Eric?

Debora: It’s a crystalline moment. You have said this is a novel about longing. And, indeed, your characters experience longing in different forms—wistful dreaminess, to longings that harbor secrets, to longings that reside on the peripheries of a darker nature, as might be in the case of Arnold. What drew you to the topic and what would you like readers to come away with from reading Closer All the Time?

Jim: Just that there are all these huge yearning lives going on everywhere around us.

Debora: I don’t think we can discuss longing without noting the scenes where we get to witness the characters in expression of their personal longings. Lead us through a thought or two from your writer point of view.

Jim: I think that expression of longing exists in every chapter, it does seem to be thematic (now that you mention it). For example you’ve got Johnny trying so desperately to think of a way to connect with his fellow-Martian son Eric, and poor Arnold going to eat repeatedly at the restaurant where Tomi works, just because she’s nice to him. You’ve got the aridity of poor Lawrence (of Arabia)’s heart, and the awkward way he and his stepbrother manage to irrigate it. And I think of Johnny and Early, their taciturn love for one another and how they honor that emotion without ever getting sentimental. Because getting sentimental just wouldn’t do, right? I wonder if all stories, when you get right down to it, have mainly to do with that human longing.

Debora: Let’s talk about your publisher, Islandport Press for a moment. They are out of Yarmouth Maine and have established an all-new February Fiction program—which honors you as the author of its first book release. It’s quite wonderful, the program and Closer All the Time being selected. I’m sure you would like to tell us more.

Jim: I love what Islandport is doing both with contemporary fiction – it is an honor to start the February Fiction series – and with their other categories of books. They have a great crew and leader. Bringing Genevieve Morgan on board as Fiction Editor was finestkind (as we say in Maine). Their focus on New England suits me to a T, of course and their moto – We tell stories – is perfect: plain-spoken but adamant. Islandport also happens to make beautiful books that I’ve bought in the past just on the promise that the covers presented.

Debora: Great team, great book, great cover. Many thanks to you and Genevieve for your literary insights and contributions and for spending time with all of us who meet online at Bill and Dave’s.

Jim: Thanks to you, Debora, for the kind words, the great questions and the close reading. And to Bill & Dave for providing such a wonderful forum for writers and readers.

Debora Black is a writer and athlete living in Steamboat Springs, CO. Check out her website here.